|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Tue. Feb. 4th, 2014

MACRO WATCH Q1 2014

NOW AVAILABLE - SUBSCRIBE

�

| FEBRUARY | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

| Complete Archives |

||||||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1 - Risk Reversal |

| 2 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 3- Bond Bubble |

| 4- EU Banking Crisis |

| 5- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 6 - China Hard Landing |

| 7 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 8 - Geo-Political Event |

| 9 - Global Governance Failure |

| 10 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 11 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 12 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 15 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 16 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 17 - Credit Contraction II |

| 18- State & Local Government |

| 19 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 20 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 21 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 22 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 23 - US Reserve Currency |

| 24 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 25 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 26 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 27 - Food Price Pressures |

| 28 - Global Output Gap |

| 29 - Corruption |

| 30 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 31 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 32- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - US Reserve Currency |

| 35- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 36 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 37 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 38 - Terrorist Event |

| 39 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

| 41 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

![]()

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers!

![]()

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

| THIS WEEKS TIPPING POINTS | MACRO NEWS | MARKET | 2013 THEMES |

DOES THIS LOOK SUSTAINABLE?

"BEST OF THE WEEK " |

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags | TIPPING POINT or 2013 THESIS THEME |

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

|||

|

GordonTLong.com SITUATIONAL ASSESSMENT Suddenly a world that seemed quite calm economically is having issues pop up all over the place. THE 7 HIGHLIGHTS YOU NEED TO KNOW

1- CHINA IS SLOWING

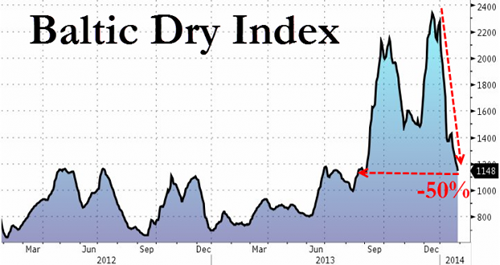

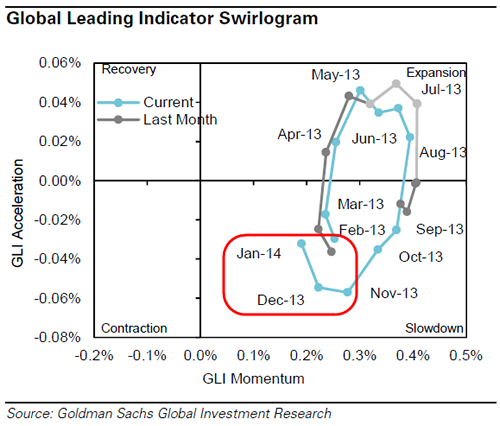

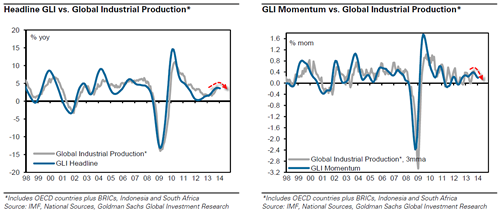

The Final HSBC Manufacturing PMI print dropped from 49.6 Flash to 49.5 - its biggest drop since June and lowest since July 2013 2- GLOBAL ECONOMY IS SLOWING The Baltic Dry Index has now plunged 51% from late December highs. Has collapsed to 5-month lows. "The January Final GLI places the global industrial cycle clearly in the ‘Slowdown’ phase, with positive but decreasing Momentum. The recent growth deceleration now looks more serious than in previous months." - Goldman Warns Global Slowdown Getting "More Serious"

3- ABENOMICS NOT WORKING

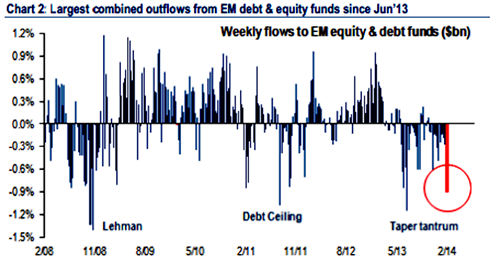

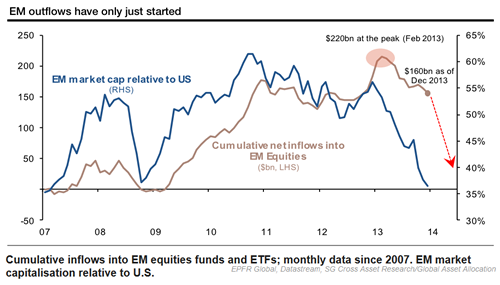

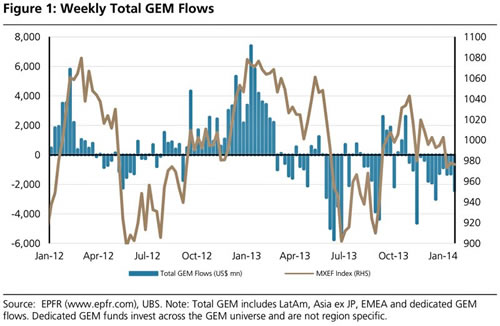

4- EMERGING MARKETS Explaining January's Volatility In One Chart Massive Outflow From Emerging Markets

5- EU BANK WORRIES ABOUT EM EXPOSURES

6- US RECOVERY WEAK

ISM Manufacturing dropped by its most since 2008 to levels not seen since May, missed by the most on record, and new orders collapsed at the fastest pace since December 1980. Real Disposable Income Plummets Most In 40 Years When real disposable personal income drops by 0.2% from a month earlier, and plummets by 2.7% from a year ago, the biggest collapse since the semi-depression in 1974, something is wrong with the US consumer. 7- BOE TIGHTENING PRESSURES

|

02-04-14 | MACRO OUTLOOK

MATA A02 |

MACRO |

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - February 2nd - February 9th | |||

| RISK REVERSAL | 1 | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 2 | ||

| BOND BUBBLE | 3 | ||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

4 |

||

| SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS [Euope Crisis Tracker] | 5 | ||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 6 | ||

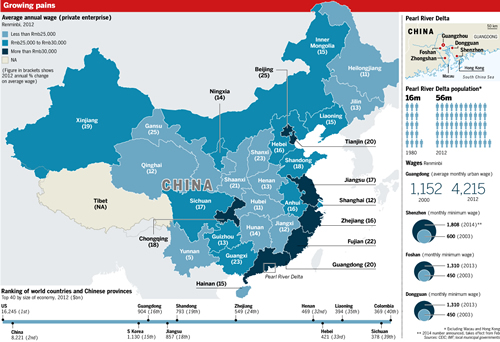

CHINA - Skilled Labor Shortages & Losing Labor Cost Advantage

China: Delta blues 01-22-14 Demetri Sevastopulo, Financial Times Shoppers will have to pay more as the world’s factory comes under wage and labour strain

Gerhard Flatz, the general manager of an Austrian factory in China that makes high-end skiwear for European brands, has a problem. He cannot find enough skilled seamstresses even though top performers can earn $1,500 a month, about eight times the local minimum wage in Heshan. “China has a shortage of skilled labour,” says Mr Flatz during a tour of the Heshan factory southwest of Guangzhou. As he walks past the pattern room where his most talented employees work, the garrulous Austrian explains that he is careful not to reveal their names to prevent poaching. “This is like the NSA”, he says with a smile, referring to the most secretive branch of the US intelligence services. Heshan is just one of the many cities in Guangdong that has transformed the province into the factory of the world. Shenzhen, the home to companies such as Huawei and Tencent, is another. When Christina Zhang moved to Shenzhen in 1983, the rural fishing county was a far cry from the booming city it has become in the three decades since Deng Xiaoping created China’s first special economic zone. “Most of the area was paddy fields,” says Ms Zhang, who works at PCH International, a logistics company. “I learnt how to ride my bicycle on Shennan Road. There were no cars [but] now it is the main road.” Since Deng launched his economic reforms in 1979, Shenzhen has changed from a tiny county of 30,000 people across the border from Hong Kong to a metropolis of 10m with one of the highest per-capita incomes in China. Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan and other regional cities form the heart of the Pearl River Delta, a region of 56m that is vital to the world economy because it produces everything from bicycles to jeans and sex toys to iPads. Dongguan alone made about 30 per cent of the toys delivered over Christmas around the globe. Yao Kang, deputy Communist party secretary of the city, says it also makes 20 per cent of the sweaters and 10 per cent of the running shoes worn by consumers. As locals say: “When there is a traffic jam in Dongguan, the world runs out of supplies.” Underscoring its phenomenal growth, Guangdong last week estimated that its economy grew 8.5 per cent to Rmb6.33tn ($1.05tn) in 2013, which would sandwich it between South Korea and Indonesia. The PRD has managed to produce cheap goods for so long because millions of migrants have been willing to work in factories making products they can rarely afford. In Shenzhen, authorities plan to raise its minimum wage by 13 per cent to Rmb1,808 next month. Although the city has the highest minimum wage in China, it would take a worker two months to earn enough to buy an iPad Air. But the system is coming under strain in ways that affect everyone from London shoppers to young Chinese in Guangdong: workers are harder to find, wages are rising rapidly, raw material and land prices are going up, the renminbi is getting stronger and other regions are becoming increasingly attractive for manufacturing. The obvious challenge to the region is labour costs, with wages in Guangdong rising at double-digit rates each year. That is unlikely to change since China is targeting nationwide annual increases of 13 per cent in its 2011-15 five-year plan, as part of a push to spur consumption and reduce the economy’s dependence on investment. Roger Lee, chief executive of TAL, a Hong Kong company with 11 factories in Asia that produces clothes for dozens of global brands, says wages have doubled over the past five years. In 2008 its Dongguan factories made clothes at half the cost of its facilities in Malaysia and Thailand but that gap has since disappeared. Crystal Group, one of Asia’s largest apparel companies with 11,000 workers in Dongguan, says organic costs – including wages and the strengthening renminbi – have risen 10-12 per cent a year over the past five years. As a result, it has been forced to shift production of commodity items such as polo shirts and underwear elsewhere. “Our strategy is to produce them in cheaper countries like Vietnam or Cambodia,” says Dennis Wong, executive director. “That is why we are still surviving.” While some companies such as Crystal are shifting production to southeast Asia, others are moving to cheaper parts of China. Samsonite, the luggage maker that outsources about 65 per cent of its production to Chinese companies, has seen many of its vendors move to provinces around Shanghai in the Yangtze River Delta. “About 80 or 90 per cent of the people we were working with were based in southern China,” says Tim Parker, chief executive of Samsonite. “Now probably the majority we purchase comes from eastern China”. . . . Despite rising labour costs, any decision to leave the delta is not easy for foreign companies and their local manufacturers. Its ecosystem – everything from clusters of suppliers to road and rail infrastructure to access to ports in Shenzhen and Hong Kong – is hard to match elsewhere without sparking other cost increases. Nick Debnam, Asia head of consumer markets at KPMG, says textile manufacturers, for example, can shift lower-skilled production to countries such as Bangladesh and Cambodia relatively easily, although wages in those countries are also rising. But other industries, such as toy manufacturing, which is concentrated in south China, are less mobile as they rely on concentrated clusters of suppliers. “There are so many ancillary bits and pieces that need to be in place, it is difficult to move the whole thing lock, stock and barrel out of China,” says Mr Debnam. For companies that are contemplating moving inland in China instead of overseas, the decision is no easier. Mr Lee of TAL says his company conducted a study five years ago that concluded that moving inland would cut labour costs by 15 per cent but that the level of infrastructure would not be as good as in Guangdong. For manufacturers that cannot easily relocate, one solution is to automate more. Samsonite’s Mr Parker says his Chinese vendors are doing exactly that. He says there is plenty of scope since many Chinese factories use far more basic equipment than, for example, those the suitcase maker employs in its own facility in Belgium. “In China . . . you will find a totally different set-up and it is driven . . . by the relatively low cost of labour,” says Mr Parker. “That’s all changing because as the costs of labour increase, so some of our more enterprising suppliers are beginning to invest in more . . . sophisticated sewing equipment in order to reduce the labour content.” Some local governments, such as Dongguan, are trying to accelerate that process with subsidies. Mr Yao, the deputy party secretary, points to the knitting town of Dalang as a successful example, saying that its factories used the government funds to buy 40,000 computerised knitting machines, reducing the need for 200,000 workers. While manufacturers juggle solutions to rising labour costs, the trend is expected to get worse for various reasons. Rising wages are partly due to local governments raising the minimum levels. In its 2011-15 economic plan, Guangdong is targeting a 40 per cent rise. But the driving cause is factories being forced to pay more to attract workers amid an increasingly tight labour market. Several factors explain the scarcity of workers but the main reason is demographics. As a result of its one-child policy, China’s working-age population – people between the ages of 15 and 59 – fell by 3.45m to 937m in 2012, in what was the first decline in many years. The labour squeeze is exacerbated in the PRD as migrant workers now have greater opportunities in their home provinces. These new opportunities are a result of central government policies aimed at promoting inland development to reduce the income gap with rich coastal regions. The “go-west” strategy is creating jobs in the interior that are particularly attractive to women who in the past left their children and moved to Guangdong for factory jobs. Another reason manufacturers are having to pay more is that workers are increasingly picky about jobs, since they have more choices as the PRD labour market shifts in their favour. Young workers are also less willing than earlier generations of migrants to toil in factories. The explosive growth in smartphones and Weibo and Weixin – known as WeChat in English – one of the most popular social media services in China, has further empowered workers by making it easier for them to learn about other factories that may have better conditions. Factories say finding female workers is increasingly difficult. The one-child policy, coupled with the general preference for male children, has skewed the gender balance, reducing the number of female workers. But young women also increasingly prefer service industry jobs over more arduous production line work. . . . The demographic and economic trends that are sparking higher wages in the PRD are forcing multinationals to raise prices, put more pressure on their suppliers to cut costs or simply accept lower profits. But some manufacturers, such as KTC in Heshan, say a more serious issue than rising wages – which can be absorbed at a cost – is the difficulty in finding enough workers with the right skills to allow production to continue. KTC has opened a factory in Laos but, as in the case of Crystal Group, the workers there make less complicated garments than in Heshan because they do not have the same skills as their Chinese peers. Top Form, a Hong Kong lingerie maker, faces a similar problem. Kevin Wong, executive director, says it closed a factory in Shenzhen and opened one in Cambodia in 2011. Mr Wong says that although wages in the southeast Asian nation are one quarter of the level in Shenzhen, that was not the main reason for the move. “It was never the labour cost. Once you don’t have the people, the overhead just kills you,” says Mr Wong, explaining that it was becoming impossible to find enough workers in Shenzhen. Regardless of the industry, the challenges in the PRD are forcing all manufacturers to find cost-cutting solutions, with the most extreme one being relocation from China. But Mr Debnam says talk of multinationals abandoning China are overblown, and that many companies do not follow through on their repeated threats to leave China. “People think that the cost issues in China and the labour issues in China will inevitably force low value-added production out of China, but it is still there,” says Mr Debnam. Given the scale of manufacturing in the PRD, the region is likely to remain the world’s factory for a long time. But manufacturers in the region and consumers buying the products face a pricier future. William Fung, chairman of Li & Fung, the big global sourcing company that procures products for everyone from Walmart to Target, says rising labour and raw material costs mean the model that served China and the world for 30 years has changed for good. “The era where China subsidised the world’s standard of living – by giving them really affordable goods from 1979-2009 – is basically over,” says Mr Fung. “People will pay what other people will probably say is a proper price.” ------------------------------------------- Policy: Keep the cage but change the bird Manufacturers are not alone in worrying about cost pressures in the Pearl River Delta. Guangdong is also promoting policies that it hopes will prevent it from losing economic competitiveness. In what Wang Yang, the former Communist party secretary of Guangdong, referred to as “Teng Long Huan Niao” – “Keep the cage, but change the bird” – the province wants to replace inefficient low-cost and labour-intensive manufacturing with more high-tech and service companies and “greener” manufacturing. As part of that push, it is developing several new economic zones to attract knowledge-based industries. They include Qianhai in Shenzhen, which it hopes to turn into a financial centre, and Nansha port in Guangzhou. Guangdong is also talking to Hong Kong and Macau about creating a big free-trade zone with the two Chinese special administrative regions. In Guangzhou, Jim Barber, president of UPS International, said the zone would provide an important boost to the region by facilitating cross-border trade and logistics. The proposal has taken on greater urgency since the central government unveiled a free-trade zone in Shanghai that is expected to provide a boost to the Yangtze River Delta, one of the main competitors to the PRD in China. Xiao Geng, a PRD expert at the Fung Global Institute in Hong Kong, says the delta needs to push ahead with integration to facilitate knowledge-based industries. But he says it is moving too slowly, mainly because of the fragmented nature of the region, which includes many local governments in addition to Hong Kong and Macau. Guangdong officials are worried about losing economic ground to Jiangsu – an increasingly prosperous Yangtze River Delta province – particularly since Hu Chunhua, the Guangdong party secretary, is a possible candidate to replace Xi Jinping as president roughly a decade from now. The PRD received a boost in 2012 when Mr Xi chose to make his first trip as the new Communist party leader to Shenzhen, following in the footsteps of Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour three decades before. “We came here to show that we’ll unswervingly push forward reform and opening up,” Mr Xi said.

|

02-03-14 | CHINA | 6 - China Hard Landing |

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

| COMMODITY CORNER - HARD ASSETS | PORTFOLIO | ||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| THESIS Themes | |||

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | |||

2013 - STATISM |

|||

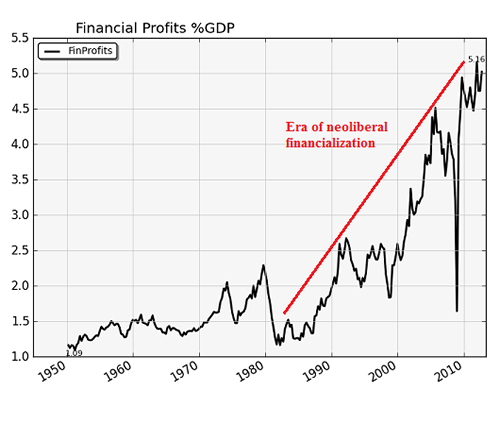

2012 - FINANCIAL REPRESSION |

|||

2011 - BEGGAR-THY-NEIGHBOR -- CURRENCY WARS |

|||

2010 - EXTEND & PRETEND |

|||

| THEMES | |||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | |||

| SHADOW BANKING -LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | |||

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | |||

| ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | |||

FLOWS: Liquidity, Credit and Debt

|

02-03-14 | THEME | ECHO BOOM |

| PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX -NATURE OF WORK | |||

| SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX -STATISM | |||

| GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | |||

| CENTRAL PLANINNG -SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER | |||

| STANDARD OF LIVING -EMPLOYMENT CRISIS | |||

Jobs Moved to Asia |

02-03-14 | THEME | STANDARD OF LIVING |

| CORPORATOCRACY -CRONY CAPITALSIM | |||

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE -MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES.. |

|||

| SOCIAL UNREST -INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | |||

| CATALYSTS -FEAR & GREED | |||

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||

| TO TOP | |||

|

|||

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP