|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

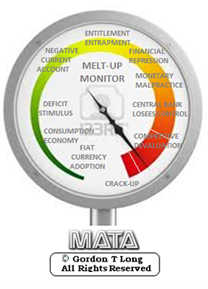

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

�

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros � |

�

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

��

"Currency Wars "

|

�

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

�

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT :� ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

�

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

�

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

�

�

Weekend June 13th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

�

�

![]()

| � | � | � | � | � |

| MAY | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| � | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | � | � | � | � |

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| � |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| � |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| � |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic | 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

�

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

�

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

�

| � |

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

� | � | Theme Groupings |

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

� |

|||

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY � |

� | � | � |

|

� | � | � |

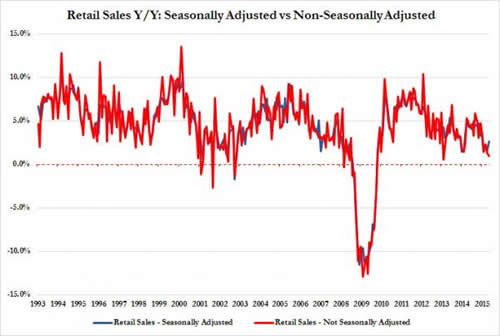

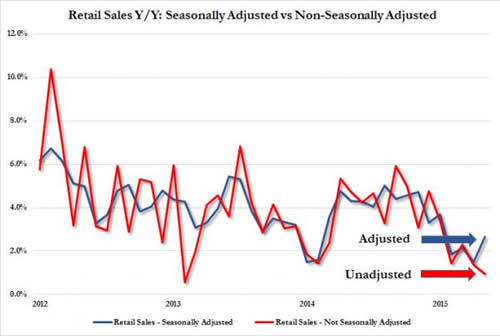

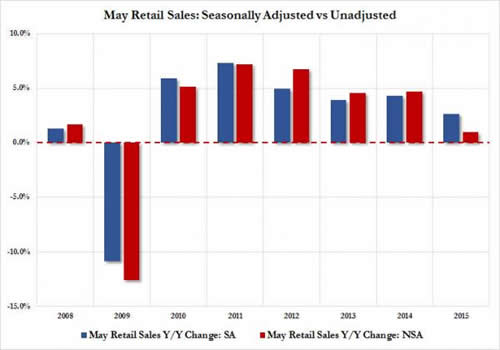

RETAIL - "Double" Seasonal Adjustments The Curious Case Of "Strong" Retail Sales: Is The US Already Applying "Double" Seasonal Adjustments 06-12-15 ZH There was some confusion why following yesterday's stronger than expected retail sales, which broke a 4-month series of disappointing data and which according to most economists were good enough to bring forward the Fed's first rate hike in a trader generation, bond yields tumbled. Well, in the aftermath of the whole "double seasonal-adjustment" travesty, in which even the BEA admitted any bad economic data (read Q1 GDP) will be "massaged" enough until it becomes good under the "scientific" pretext of "residual seasonality", and following the suggestion of�Dynamika Capital's Alexander Giryavets, we decided to take a look at�not seasonally adjusted�retail sales. We found something interesting. The thing about retail sales is that while they are supposed to smooth out month-to-month changes in any given data series, they should be virtually identical on a annual, year-over-year basis. After all the same "seasonal" adjustment that was applicable this May, was applicable last May, the May before it, and so on, unless of course, there was some massive, climatic or otherwise shift to the underlying reality. To the best of our knowledge there wasn't. And indeed, when looking at the annual change in headline retail sales data we find that, as expected, the seasonally-adjusted (blue) and unadjusted (red)retail sales series are almost identical... ... but not quite. If one zooms in on the most recent data, one finds something surprising: a substantial rebound in SA retail sales, which according to the Dept. of Commerce rose 2.7% while unadjusted retail sales rose by just 1.0%,the worst montly print in over two years and hardly inspiring confidence that the economy is strong enough for the Fed to engage in a rate hike. To isolate the problem we decided to look at only the annual (YoY) change in May data. The chart below shows the surprising finding: while every year for the past 4 years the�Unadjusted�May data was equal to or stronger than the�Adjusted�retail sales print, in May of 2015 this was reversed, and quite substantially. To show just how much of an outlier May 2015 was compared to May in prior years, here is the seasonal "adjustment ratio" for the month of May for every year from 2008 to 2015, by which we define the ratio of "seasonally adjusted" to "unadjusted" retail sales. Spotting the outlier should be easy enough. So, our question: while we know that the US Department of Truth, err. Commerce, will soon adjust GDP data for all weak quarters higher just so the narrative of a rebounding economy isn't lost when one looks at the actual fact, has this "residual seasonality" adjustment already been applied to retail sales? Because we fail to understand just why the seasonal adjustment to May retail data should be as profound as shown above. Source: (Double?)�Seasonally-Adjusted�and�Unadjusted�retail sales |

06-13-15 | SII US IND CONS |

� |

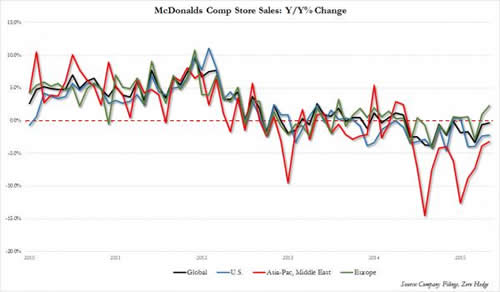

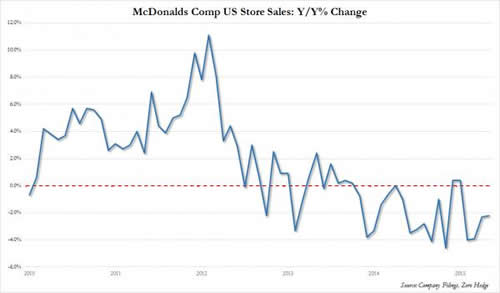

RETAIL - Why McDonalds Is Ending Monthly Sales Reports Why McDonalds Is Ending Monthly Sales Reports: Global Sales Drop For 12 Consecutive Months 06-08-15 ZH Ten days ago we reported with much amusement that the "turnaround story" that is McDonalds has decided to pull the oldest trick in the collapsing business book, and would stop reporting its monthly comparable sales starting with the month of June. Moments ago MCD reported its May comp store sales which confirmed what we cynically noted is the reason for the data halt, namely that no matter what it does, MCD simply can not "turnaround" its foundering business, and after a drop of -0.6% in April, May global comp sales dropped once again, this time by -0.3%. This was the 12th consecutive month of global comparable store declines. Next month will be the 13th. There won't be a 14th. The good news for Europe is that with a jump of 2.3% in May comp store sales, the European recovery is clearly taking hold and the tens of millions of unemployed youths can finally afford a 99 cent meal. But perhaps the biggest irony is that the drop was driven not by Europe or Asia, where one would expect the strong dollar to be wreaking havoc on US-denominated sales, but in the US, where same store sales dropped -2.2%, more than the -1.7% expected. We wonder if the decline in USD-denominated US sales will also gain be blamed on the strength of the US currency? Finally, as we have said all along, it really is time for MCD's new boss Steve Easterbrook to start wearing many more pieces of flair or he will join his predecessor Don Thompson in "retiring" prematurely any month now. � |

06-13-15 | SII US IND CONS |

� |

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - June 7th, 2015 - June 13th, 2015 | � | � | � |

| BOND BUBBLE | � | � | 1 |

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | � | � | 2 |

STUDIES - CENTRAL BANKING RISK They Mave Have Lost Control |

� | � | � |

GLOBAL RISK

400 Billion Reasons Why Ebbing Currency Reserves Threaten Bonds 06-05-15 Bloomberg There’s a $400 billion reason to worry if you’re a bond investor. That’s how much global currency reserves have shrunk since reaching a record $12 trillion last August, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The decline is another potential source of volatility in debt markets rocked this week in part by ebbing deflation fears in Europe and speculation the U.S. Federal Reserve will soon raise interest rates. That’s because contracting reserves leave countries with less money to recycle into bonds, removing a key support, strategists at Montreal-based brokerage Pavilion Global Markets Ltd., said in a note sent to clients on Thursday and titled “Falling Reserves, Rising Yields.” Periods of falling reserves historically coincided with increased fixed-income volatility, as measured by a market stress indicator created by the ECB and based on fluctuations in the German 10-year bond, according to the Pavilion team, led by Pierre Lapointe. Bond markets jumped in both 2008 and 2011, the same times as the combined reserves of China, Saudi Arabia, Japan and Switzerland were dipping by Pavilion’s reckoning. “We expect this time to be no different,” Lapointe and colleagues wrote, predicting a more skittish bond market will also cause equities and currencies to trade more wildly. Furthermore, they found recent outflows from Europe’s bond market correlate with monthly declines in China’s foreign-exchange reserves, which have fallen to $3.7 trillion from a peak of $4 trillion last June. Emerging markets exiting European debt “could explain the recent move in bund yields despite underwhelming data and continued Greek drama,” the Pavilion strategists wrote. |

06-09-15 | STUDIES | 1- Bond Bubble 2 - Risk Reversal � |

GLOBAL RISK For six years, the world has operated under a complete delusion that Central Banks somehow fixed the 2008 Crisis. All of the arguments claiming this defied common sense. A 5th�grader would tell you that you cannot solve a debt problem by issuing more debt. If the below chart was a problem BEFORE 2008… there is no way that things are better now. After all, we’ve just added another $10 trillion in debt to the US system. Similarly, anyone with a functioning brain could tell you that a bunch of academics with no real-world experience, none of whom have ever started a business or created a single job can’t “save” the economy. However, there is an AWFUL lot of money at stake in believing these lies. So the media and the banks and the politicians were happy to promote them. Indeed, one could very easily argue that nearly all of the wealth and power held by those at the top of the economy stem from this fiction. So it’s little surprise that no one would admit the facts that: the Fed and other Central Banks not only don’t have a clue how to fix the problem, but that�they actually have almost no incentive to do so. So here are the facts:

We are heading for a crisis that will be exponentially worse than 2008. The global Central Banks have literally bet the financial system that their theories will work. �They haven’t. All they’ve done is set the stage for an even worse crisis in which entire countries will go bankrupt. |

06-10-15 | STUDIES | 1- Bond Bubble 2 - Risk Reversal � |

GLOBAL RISK "With so many bonds stuck inside the�Fed, there was now a scarcity of good collateral to go around in other markets. This was another type of illiquidity that left markets on the knife-edge of collapse."

"They concluded with identifying the risk of a flash crash that will not be able to bounce back & would be "the beginning of a global contagion and financial panic worse than what the world went through in the financial crisis" Good Evening, Mr. Bond 06-09-15 Jim Rickards One of the most intriguing players in the Watergate scandals that mesmerized the U.S. from 1972-74 was nicknamed “Deep Throat” after the title of a popular adult film of the time. Deep Throat was an anonymous source who provided important clues to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, reporters for�The Washington Post�that helped them unravel the web of burglary, dirty tricks, payoffs, perjury and coverups emanating from the Nixon White House. These illegal activities all fell under the heading of “Watergate,” a political scandal that led finally to the resignation of Richard Nixon as president. The identity of Deep Throat was one of the best-kept secrets of the 20th century. It was only in 2005, over 30 years after the Watergate scandal broke, that Deep Throat was revealed to be W. Mark Felt, the deputy director of the FBI at the time. Given the sensitivity of Felt’s position, and the journalistic ethic that requires protection of sources, it is perhaps not surprising that Deep Throat’s identity was so well hidden for so long. But reporters are not the only ones who need to shield the identities of valued sources. Sensitive issues arise all the time in economic policy and geopolitics. Principals may be willing to share information with trusted associates, but only if their names are not revealed. This kind of cooperation preserves access to information in the future and provides a valuable service to readers if the information can be shared. This point was brought home in a recent article in�The New York Times�in which Arvind Subramanian, chief economic adviser to the government of India, while referring to U.S. economic weakness said, “People can’t be too public about these things.” I recently had dinner in my hometown of Darien, Connecticut, with one of the best sources on the inner workings of the U.S. Treasury bond market. Our dinner took place at the Ten Twenty Post bistro, the same restaurant I wrote about in my first book,�Currency Wars. It was there that a friend and I invented the scenario involving a Russian and Chinese gold-backed currency that we played out in the Pentagon-sponsored financial war game described in that book. Now I had returned for another private conversation with another friend. But this time we were not discussing fictional scenarios for a war game. The conversation involved real threats to real markets happening in real-time. I can’t reveal the identity of my dinner companion, but suffice it to say he is a senior official of one of the largest banks in the world and has over 30 years’ experience on the front lines of bond markets. He has been a regular participant in the work of the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, a private group that meets behind closed doors with Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury officials to discuss supply and demand in the market for Treasury securities and to plan upcoming auctions to make sure markets are not taken by surprise. He’s an insider’s insider who speaks regularly with major bond buyers in China, Japan and the big U.S. funds like PIMCO and BlackRock. For purposes of this article, let’s just call him “Mr. Bond.” Over white wine and oysters, I told Mr. Bond about my view of systemic risk in global capital markets. In effect, I was using Bond as a reality check on my own analysis. This is an important part of the analytic technique we use in�Strategic Intelligence. First, develop a thesis with the best information available. Then test the thesis against new information every chance you get. You’ll soon know if you’re on the right track or need to revise your thinking. My conversation with Mr. Bond was the perfect chance to update my thesis. I told Bond that markets appeared to be in a highly paradoxical situation. On the one hand, I had never seen so much liquidity. Literally trillions of dollars of cash were sloshing around the world banking system in the form of excess reserves on deposit at central banks — the result of massive money printing since 2008. On the other hand, something was definitely wrong with liquidity. The Oct. 15, 2014, “flash crash” of rates in the Treasury bond market was a case in point. On that day, the yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note fell 0.34% in a matter of minutes. This is a market in which a change of 0.05% in a single day is considered a big move. The Oct. 15 flash crash was the second most volatile day in over 50 years. Something was strange when there was massive liquidity in cash and complete illiquidity in notes�at the same time. Here’s a chart showing the bond market flash crash on a minute-by-minute basis. The time of day is along the horizontal axis and the yield-to-maturity is on the vertical axis. You can see how yields crashed from 2.2% to 1.86% between 7:00 a.m. and 9:45 a.m., with most of that crash taking place in just a few minutes between 9:30 and 9:45, just after the stock market opened. Almost no one alive today in the bond market had ever seen anything like this. I told Mr. Bond that this Treasury market flash crash looked a lot like the stock market flash crash of May 6, 2010, when the Dow Jones industrial average index fell 1,000 points, about 9%, in a matter of minutes, only to bounce back by the end of the day. This kind of sudden, unexpected crash that seems to emerge from nowhere is entirely consistent with the predictions of complexity theory. Increasing market scale correlates with exponentially larger market collapses. It was important to me to move beyond the theoretical and see whether an active market participant like Mr. Bond agreed. His answer sent a chill down my spine. It’s worse than you know He said, “Jim, it’s worse than you know.” Mr. Bond continued, saying, “Liquidity in many issues is almost nonexistent. We used to be able to move $50 million for a customer in a matter of minutes. Now it can take us days or weeks, depending on the type of securities involved.” According to Mr. Bond, there were many reasons for this.

FROM MARKET MAKERS TO AGENTS Taken together, these regulatory changes meant that banks were no longer willing to step up and make two-way customer markets as dealers. Instead, they acted as agents and tried to match buyers and sellers without taking any risk themselves. This is a much slower and more difficult process and one than can break down completely in times of market distress. HFT COMES TO BOND MARKET In addition, new automated trading algorithms, similar to the high-frequency trading techniques used in stock markets, were now common in bond markets. This could add to liquidity in normal times, but the liquidity would disappear instantly in times of market stress. The liquidity was really an illusion, because it would not be there when you needed it. The illusion was quite dangerous to the extent that customers leveraged their own positions in reliance on the illusion. If the customers all wanted to get out of positions at once, there would be no way to do it and markets would go straight down. HIGH QUALTIY SWAPS COLLATERAL Another factor that Mr. Bond and I discussed over dinner was the shortage of high-quality collateral for swap and other derivatives transactions. This was the flip side of money printing by the Fed. When the Fed prints money, the do it by purchasing bonds in the market and crediting the seller with money that comes out of thin air. This puts money into the system, but it takes the bonds out of circulation. But banks need the bonds to support collateralized transactions in the swap markets. With so many bonds stuck inside the Fed, there was now a scarcity of good collateral to go around in other markets. This was another type of illiquidity that left markets on the knife-edge of collapse. As Mr. Bond and I finished our meal and polished off the last of wine, we agreed on a few key points. Markets are subject to instant bouts of illiquidity despite the outward appearance of being liquid. There would be more flash crashes, probably worse that the ones in 2010 and 2014. COMING FLASH CRASH TRIGGER Eventually, there would be a flash crash that would not bounce back and would be the beginning of a global contagion and financial panic worse than what the world went through in 2008. This panic might not happen tomorrow, but then again it could. The solution for investors is to have some assets outside the traditional markets and outside the banking system. These assets could be physical gold, silver, land, fine art, private equity or other assets that don’t rely on traditional stock and bond markets for their valuation. |

06-11-15 | STUDIES | 1- Bond Bubble 2 - Risk Reversal � |

GLOBAL RISK The Central Banks Are Losing Control Of The Financial Markets 06-07-15 Submitted by Michael Snyder of�The Economic Collapse�blog Every great con game eventually comes to an end.� For years, global central banks have been manipulating the financial marketplace with their monetary voodoo.� Somehow, they have convinced investors around the world to invest�tens of trillions of dollars�into bonds that provide a return that is�way under the real rate of inflation.� For quite a long time I have been insisting that this is highly irrational.� Why would any rational investor want to put money into investments�that will make them poorer�on a purchasing power basis in the long run?� And when any central bank initiates a policy of “quantitative easing”, any rational investor should immediately start demanding a higher rate of return on the bonds of that nation.� Creating money out of thin air and pumping into the financial system devalues all existing money and creates inflation.� Therefore, rational investors should respond by driving interest rates up.� Instead, central banks told everyone that interest rates would be forced down, and that is precisely what happened.� But now things have shifted.� Investors are starting to behave more rationally and the central banks are starting to lose control�of the financial markets, and that is a very bad sign for the rest of 2015. And of course it isn’t just bond yields that are out of control.� No matter how hard they try, financial authorities in Europe can’t seem to fix the problems in Greece, and the problems in Italy, Spain, Portugal and France just continue to escalate as well.� This week, Greece became the very first nation to miss a payment to the IMFsince the 1980s.� We’ll discuss that some more in a moment. Over in Asia, stocks are fluctuating very wildly.� The Shanghai Composite Index plunged by�5.4 percent�on Thursday before regaining all of those losses and actually closing with a gain of�0.8 percent.� When we see this kind of extreme volatility, it is a very bad sign.� It is during times of extreme volatility that markets crash. Remember, stocks generally tend to go up during calm markets, and they generally tend to go down during choppy markets.� So most investors do not want to see lots of volatility.� Unfortunately, that is precisely what we are witnessing all over the world right now.� The following comes from�the Wall Street Journal…

Sometimes when bond yields go up, it is because investors are taking money out of bonds and putting it into stocks because they are feeling really good about where the stock market is heading.� This is not one of those times.� As Peter Tchir has noted, the huge moves in the bond market that we are now seeing are the result of�“sheer panic in the market”…

But this wasn’t supposed to happen. After watching the Federal Reserve be able to successfully use quantitative easing to drive down interest rates, the European Central Bank decided to try the same thing.� Unfortunately for them, investors are starting to behave more rationally.� The central banks are starting to lose control of the financial markets, and bond yields are soaring.� I think that�Peter Boockvar�summarized where we are currently at very well when he stated the following…

And if global investors continue to move in a rational direction, this is just the beginning.� Bond yields all over the planet should be much, much higher than they are right now.� What that means is that bond prices potentially have a tremendous amount of room to go down. One thing that could accelerate the global bond crash is the crisis in Greece. Negotiations between the Greeks and their creditors have�been dragging on for four months, and no agreement has been reached.� Now, Greece has missed the loan payment that was due to the IMF on June 5th, and it is asking the IMF to bundle all of the payments that are due this month�into one giant payment at the end of June…

Of course that payment will not be made either if a deal does not happen by then.� And with each passing day, a deal seems less and less likely.� At this point, the package of “economic reforms” that the creditors are demanding from Greece is completely unacceptable to Syriza.� The following comes from an article�in the Guardian…

Ultimately, I don’t believe that we are going to see an agreement. Why? Well, I tend to agree with this bit of analysis�from Andrew Lilico…

You can read the rest of his excellent article�right here. Without a deal, the value of the euro is going to absolutely plummet and bond yields over in Europe will go through the roof.� I am fully convinced that this is the beginning of the end for the eurozone as it is currently constituted, and that we stand on the verge of a great European financial crisis. And of course the financial crisis that is coming won’t just be in Europe.� The global financial system is more interconnected than ever, and there are�tens of trillions of dollars in derivatives�that are tied to foreign exchange rates and�505 trillion dollars�in derivatives that are tied to interest rates.� When this giant house of cards collapses, the central banks won’t be able to stop it. In the end, could we eventually see the entire central banking system itself totally collapse? That is what�Phoenix Capital Research�believes is about to happen…

We stand at the precipice of the greatest economic transition that any of us have ever seen. Even though things may seem very “normal” to most people right now, the truth is that the global financial system is fundamentally flawed, and cracks in the system are starting to appear all over the place. When this system does collapse, it will take most people entirely by surprise. But it shouldn’t. All con games eventually fall apart in the end, and we are about to learn that lesson the hard way. |

06-09-15 | STUDIES | 1- Bond Bubble 2 - Risk Reversal � |

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | � | � | 3 |

| CHINA BUBBLE | � | � | 4 |

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | � | � | 5 |

EU BANKING CRISIS |

� | � | 6 |

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � |

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � |

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | � | � | � |

| � | � | � | |

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET | � |

� | � |

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � |

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � |

| � | � | � | |

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

FINANCIAL REPRESSION PURU SAXENA is Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Puru Saxena Wealth Management in Hong Kong. Mr. Saxena has extensive investment experience and he is a registered investment advisor/money manager with the Securities & Futures Commission of Hong Kong. Highly respected in the investment management business, he is a regular guest on various media such as CNN, BBC, CNBC, Bloomberg, Reuters and a host of other channels. Furthermore, he is regularly featured in several publications such as Barron’s, Hong Kong Economic Times, South China Morning Post, Benchmark magazine, Hong Kong Business and China Daily. Mr. Saxena is also the editor of our monthly economic report – Money Matters. Our highly acclaimed publication is read by professional and retail investors in numerous countries. He first began publishing his monthly economic report in June 2000 and it has now attracted a wide following. PURU SAXENA talks FINANCIAL REPRESSION

31 Minute Video Interview FINANCIAL REPRESSION "We have been through a huge financial crisis in 2008 which brought the world's banking system to it knees. The US housing market was on it knees. It was the worst recession, if not depression that the US faced in a long time. It affected all the global markets. So rightly or wrongly - wrongly in my view - the central banks decided to bailout everyone in site by keeping interest rates near zero and launching Quantitative Easing programs (which is essentially bond buying or asset swapping) which is printing new money and buying toxic bonds from the banks and thereby cleaning up the banks balance sheets - making sure the banking system survives."

"It is essentially a transfer of wealth from savers to the borrowers and debtors." "This has managed to stabilize the system temporarily but is really not good for society!" UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES "The problem is everyone has become accustomed to being bailed out! Now there is no such thing as a bankruptcy! Everyone knows (especially the banks), if they make mistakes someone will bail them out either the central banks or the government. It has increased risk taking. "It has increased risk taking." "I never felt QE was capable of increasing business activity because this is not really a supply side problem but a demand side problem. You have households all over the world already choking on debt. The last thing they want to do is borrow more money even if you drop rates to zero or give them money to borrow, they just are not going to do it! A DEMAND PROBLEM "When people ask why QE hasn't caused inflation or hyperinflation, the answer is simple: households in the west were in no position to borrow money at even zero interest rates. The aggregate demand for new debt or credit was simply not there. By swapping assets the central banks have managed to cleanup the banking system but they have not been able to ignite the risk appetite at the household level". "We have a Demand problem, NOT a Supply Side problem!" This is a global problem! "Even in Hong Kong, 2 years ago it was teaming with mainline Chinese tourists which now are simply not coming. Retail sales in Hong Kong have fallen significantly. Spending is hurting as the middle class has been obliterated! The rich have become richer as assets have increased and savers have been penalized. This policy of QE and Financial Repression has really helped the elite of the world - who have had access to financial leveraging." LOW GROWTH ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT The core problem to Puru Saxena is:

"Historically we have seen, whenever an economy passes through an extremely slow growth, sluggish environment where there is a lack of aggregate demand and you have deflationary pressures, long term interest rates have always gone down. The tendency of long-term interest rates is to drift lower in this environment. Long-term interest rates are normally set by the rate of economic activity as well as the real rate of inflation. At the moment we don't really have much inflation or at least forces on inflation anywhere in the developed world and economic activity is zero or even negative!" Long-term interest rates are price appropriately for the current economic activity! There is much, much more in this 31 minute macroeconomic view of the world and the investment opportunities it presents.

� AUDIO ONLY - choose an alternate listening method... |

06-08-15 | � | |

�

The Lessons on Capital Controls from Argentina Sovereign Man explains how Argentina's government is bankrupt & has been implementing countless sets of controls including exchange price controls, media controls, exchange controls & capital controls [financial repression] ..�"When governments find themselves in financial trouble because of the stupid decisions that they’ve made, their first response is to award themselves even more power to make even stupider decisions. And among the stupidest decisions that any government can make is imposing capital controls .. something that Argentina has in abundance." .. these capital controls include prohibitions to leave the country with more than U.S.$10,000 in cash & significant paperwork & bureaucracy to wire funds out of the country .. also there is a 30% difference in the official exchange rate with the market exchange rate so that your wired funds leaving the country are effectively 30% less than you think .. "What happens with capital controls: you see a rapid decline in your standard of living as the government traps your savings in a bankrupt system .. It’s like lying on the ground with a blindfold on while the government builds a coffin all around you .. Little by little they fasten together all the sides, and then the top, nail by nail. Capital controls are like a coffin for your savings." |

06-08-15 | � | |

� Austrian School Economist Carl Menger: "Money Emerges from a Free Market Economy, Not From Government Decree" Dr. Joseph Salerno on The War on Cash "The free market provides the prospect of an escape from the fiscal police state that seeks to stamp out the use of cash [financial repression] through either depreciation of central-bank-issued currency combined with unchanged currency denominations or direct legal limitation on the size of cash transactions. As Carl Menger, the founder of the Austrian School of economics, explained over 140 years ago, money emerges not by government decree but through a market process driven by the actions of individuals who are continually seeking a means to accomplish their goals through exchange most efficiently. Every so often history offers up another example that illustrates Menger’s point. The use of sheep, bottled water, and cigarettes as media of exchange in Iraqi rural villages after the U.S. invasion and collapse of the dinar is one recent example. Another example was Argentina after the collapse of the peso, when grain contracts priced in dollars were regularly exchanged for big-ticket items like automobiles, trucks, and farm equipment. In fact, Argentine farmers began hoarding grain in silos to substitute for holding cash balances in the form of depreciating pesos." � |

06-08-15 | � | |

�

Mark Thornton on The True Meaning of Financial Repression Financial Survival Network interviews Mises Institute's Mark Thornton .. Thornton writes: "With politicians and central bankers seemingly gone mad with their obsession for money printing and ultra low interest rates, it is nice to know that academic economists have a term (i.e., financial repression) for the policies that have created our current economic conditions." .. the term financial repression dates back to 1973 when 2 Stanford University economists - Edward Shaw & Ronald McKinnon .. identifies 2 major macroprudential policies of financial repression in use - ZIRP or zero interest rate policy of central banks to keep interest rates & lending rates at or near 0 - this makes the interest rate on government debt low .. & the second is QE or quantitative easing is the central bank policy of buying up government debt from banks - this increased demand increases the price of government bonds & reduces the interest rates on those bonds .. Take a look at the frescoes Mark refers to in his article and see if you recognize a parallel to modern America: The Allegory of Good and Bad Government .. 20 minutes � |

06-08-15 | � | |

|

BCA Research Chief Economist Martin Barnes: "Financial Repression is Here to Stay" BCA Research's Chief Economist Martin Barnes sees financial repression as "here to stay" for the long-term, given the challenges of low economic growth & high debt globally .. Barnes has written a special report to explain why debt burdens are moe likely to rise than fall over the short & long run given demogaphic trends & the low odds of another economic boom .. BCA Research: "If governments cannot easily bring debt ratios down to more sustainable levels, then the obvious solution is to make high debt levels easier to live with. This can be done be keeping real borrowing costs down and by regulatory pressures that encourage financial institutions to hold more government securities. In other words, financial repression is the inevitable result of a world of low growth and stubbornly high debt. Martin argues that central banks are not overt supporters of financial repression, but they certainly are enablers because they have no other options other than to keep rates depressed if they cannot meet their growth and/or inflation targets. A world of financial repression is an uncomfortable world for investors as it implies continued distortions in asset prices, and it is bound to breed excesses that ultimately will threaten financial stability." |

06-08-15 | � | |

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| � | � | ||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

� | � | � |

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | � | THEME | � |

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

� | THEME |  |

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | � |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | � |

II-ECONOMIC |

� | � | � |

| GLOBAL RISK | � | � | � |

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | � |

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | � |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | � |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | � | � | � |

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | � | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

III-FINANCIAL |

� | � | � |

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

FLOWS - Liqudity, Credit and Debt Treasury volumes raise liquidity concerns 06-12-15 FT World’s most actively traded market ‘not functioning as normal’ One of the more worrying aspects of the sell-off in the�US Treasury market�is the relative paucity of actual selling. While the 10-year Treasury yield has risen from below 1.9 per cent in mid-April to a peak of almost 2.5 per cent this week, traders say the increase has been driven by lower amounts of trading than the steepness of the climb would suggest. Investors, bankers and analysts have in recent years been worrying over the deteriorating trading conditions in corporate bond markets, but increasingly some are fretting that the liquidity of the biggest and most actively traded market of them all —�US Treasuries�— should be the biggest concern. “It’s definitely not functioning as normal,” notes Jack Flaherty, a New York-based bond fund manager at GAM. Deutsche Bank ’s strategists have estimated that the average turnover in investment-grade and high-yield bond markets has declined 50 per cent and 30 per cent respectively from peaks in 2006-07. But the German bank’s measure of Treasury liquidity — the average proportion of the market that changes hands on a daily basis — had slumped 70 per cent since its noughties peak. “The focus on liquidity is correct, but people are looking in the wrong place,” says Oleg Melentyev, one of the note’s authors. “High-yield investors are very aware of the illiquidity in their market, but people are less aware of the problem in Treasuries. So that’s probably where we’ll see the bad surprises.” The US government bond market remains vastly more liquid than its counterparts. Using Deutsche Bank’s measure of liquidity it is about 10 times more actively traded than investment-grade corporate debt. In fact by some measures the�Treasury market�looks in rude health. Despite the rise in yields, the US government’s benchmark borrowing costs remain at levels that would have been unimaginable a few years ago. Moreover in absolute terms daily trading volumes are robust at about $500bn a day, and the difference between the price at which investors are willing to buy or sell Treasuries — a widely watched gauge of liquidity — has shrunk down to pre-crisis lows. These measures of liquidity, however, do not necessarily reflect the diminishment in the market’s “depth”, or the ability of investors to trade big chunks of Treasuries easily without unduly moving the price. To measure this JPMorgan’s bond strategy team took the top three bids and offers in “on-the-run” (newly issued) Treasuries in the early morning, when trading is more active. They found that depth deteriorated severely during the financial crisis, and occasionally at times of stress since, but has averaged about $171m for 10-year Treasuries over the past eight years. This year the depth has averaged only $116m. Franklin Templeton has not experienced any significant problems trading US government debt, according to Mike Materasso, head of Treasuries at the asset manager. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried,” he says. “The stats paint a potentially bleak picture.” The decline in Treasury liquidity has many causes. Although the size of the market has swollen since the financial crisis, much of the extra issuance has been absorbed by the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing programme, or snapped up by foreign central banks keen to bolster currency reserves. That leaves less for actual trading. At the same time the footprint and influence of big banks known as the primary dealers have faded. Commercial and regulatory pressures have forced them to trim involvement in the�Treasury market. That hamstrings their ability to act as shock-absorbers in turbulent times — as became clear when the�Treasury market careened up and down�last October. The turmoil was brief but so severe that some banks were forced to shut their automated electronic trading systems. “When you have moves like this you’re just hanging on for dear life,” says one senior trader. The holdings of the Fed and big overseas investors also have a knock-on effect on the “repo market”, which greases the global financial system by allowing investors to trade safe collateral — such as Treasuries — for short-term funding. Stricter regulation has gummed up the repo market, and in turn weighed on the liquidity of the underlying securities. While US Treasuries remain a cornerstone of the global financial system, as the default risk-free assets of choice, one of their main advantages is liquidity. If that is falling then investors might demand slightly higher yields as compensation. JPMorgan has nudged up its year-end forecast for the 10-year yield from 2.40 per cent to 2.55 per cent, despite no change to its economic views. “Over the past few years, many market participants have come to fear this [lack of liquidity] of corporate bonds, and this is probably one reason why corporate spreads have remained stubbornly wide,” wrote Jan Loeys, head of global asset allocation, in a note. “Now the fear and reality have spread to what were before considered the most liquid bonds in the world.” |

06-12-15 | THEMES FLOWS |

FLOWS |

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | � | THEME | � |

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | � |

| GENERAL INTEREST | � |

� | � |

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

| TO TOP | |||

| � | |||

�

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

���

���

TO TOP

�

�

�

�

�� TO TOP

�

�

"In the process they have held interest rates at zero for a long long time, not only in the US, Europe and a lot of other countries in the developed world, which is penalizing the savers to the benefit of the borrowers and debtors. They are especially hurting people at retirement or close to retirement because suddenly their passive income which they had worked so hard to accumulate all their life disappears!

"In the process they have held interest rates at zero for a long long time, not only in the US, Europe and a lot of other countries in the developed world, which is penalizing the savers to the benefit of the borrowers and debtors. They are especially hurting people at retirement or close to retirement because suddenly their passive income which they had worked so hard to accumulate all their life disappears!