|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

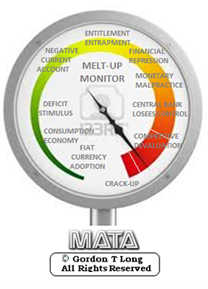

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Mon. Sept 7th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

onTWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

ANNUAL THESIS PAPERS

FREE (With Password)

THESIS 2010-Extended & Pretend

THESIS 2011-Currency Wars

THESIS 2012-Financial Repression

THESIS 2013-Statism

THESIS 2014-Globalization Trap

THESIS 2015-Fiduciary Failure

NEWS DEVELOPMENT UPDATES:

FINANCIAL REPRESSION

FIDUCIARY FAILURE

WHAT WE ARE RESEARCHING

2015 THEMES

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY

PENSION POVERITY

WAR ON CASH

ECHO BOOM

PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX

FLOWS - LIQUIDITY, CREDIT & DEBT

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

- COMING NWO

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING

(A) Active, (C) Closed

MATA

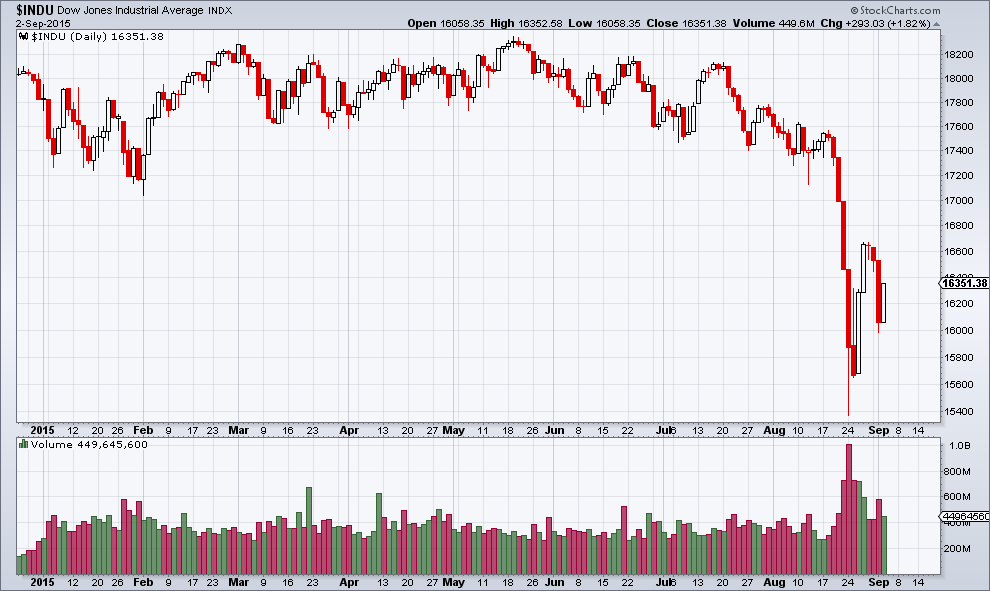

Q3 '15- Chinese Market Crash

(A)

Q3 '15-

GMTP

Q3 '15- Greek Negotiations

(A)

Q3 '15- Puerto Rico Bond Default

MMC

OUR STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS (SII)

NEGATIVE-US RETAIL

NEGATIVE-ENERGY SECTOR

NEGATIVE-YEN

NEGATIVE-EURYEN

NEGATIVE-MONOLINES

POSITIVE-US DOLLAR

ARCHIVES

| AUGUST | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

| 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

Reading the right books?

No Time?We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||||||||||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

|

|||||||||||

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

||||||||||

|

CHECK OUT OUR PAGE DEDICATED TO FINANCIAL REPRESSION The Financial Repression AuthorityTM

|

|||||||||||

| THESIS & THEMES | |||||||||||

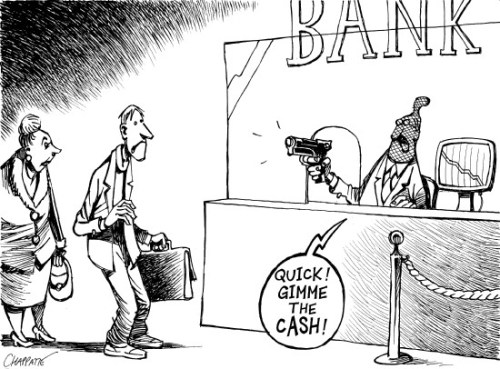

FINANCIAL REPRESSION - War on Cash Life In A Cashless World: How Cash Became A Policy Tool – An Interview With Dr. Harald MalmgrenSubmitted by Tyler Durden on 09/06/2015 - 08:45

Banks in the US and Europe are trying to develop a cashless transactions system. The concept is to establish a comprehensive ledger for a business or a person that records everything received and spent, and all of the assets held – mortgages, investment portfolios, debts, contractual financial obligations, and anything else of market value. There would be no need for cash because the ledger would tell you and anyone you were considering a transaction with how much is available and would be transactable at any specific moment. This is not a dreamy idea. Blythe Masters is leading a new business effort to develop a universal cashless system. Not only is she gathering significant investor interest, but the Federal Reserve and various US Government agencies have become keenly interested in the potential usefulness and efficiencies of a universal cashless system The Case For Outlawing CashSubmitted by Tyler Durden on 09/06/2015 - 14:15

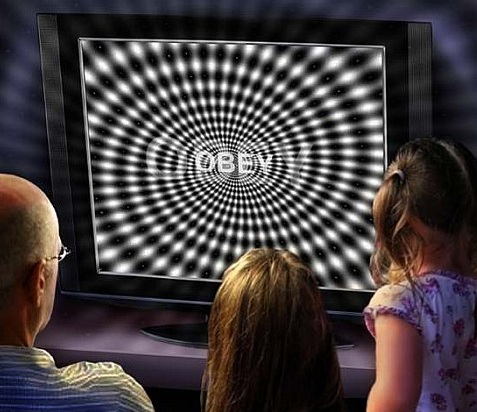

September is here. As expected, market volatility is increasing. The Great Zombie War is intensifying. And investors are getting scared. Now they even want to do away with the State’s own scrip... You see where this is going, don’t you? If the feds are able to ban cash, they will have you completely under their control. You will invest when they want you to invest. You will buy when and what they want you to buy. You will be forced to keep your money in a bank – a bank controlled, of course, by the feds. The Danger Of Eliminating CashSubmitted by Tyler Durden on 09/07/2015 - 18:10

In the early days of central banking, one primary objective of the new system was to take ownership of the public's gold, so that in a crisis the public would be unable to withdraw it. Gold was to be replaced by fiat cash which could be issued by the central bank at will. This removed from the public the power to bring a bank down by withdrawing their property. A primary, if unspoken, objective of modern central banking is to do the same with fiat cash itself.

|

09-07-15 | ||||||||||

Submitted by Erico Matias Tavares of Sinclair & Co. Life In A Cashless World: How Cash Became A Policy Tool – An Interview With Dr. Harald MalmgrenCash as a Policy Tool – An Interview with Dr. Harald Malmgren The Hon. Dr. Harald Malmgren, Chief Executive of Malmgren Global, advises governments and companies on international trade and investment. A former senior aide to US Presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford and to Senators Abraham Ribicoff and Russell Long, US Senate Committee on Finance, he is a frequent author of articles and papers on global economic, political and security affairs. E. Tavares: Prof. Malmgren, it is a pleasure and a privilege to be speaking with you today. We would like to talk about cash – the actual bills and coins – as a policy tool, something which is not often discussed. Before we get into that, what are the main developments you are seeing in the transactional space around the world? H. Malmgren: Banks in the US and Europe are trying to develop a cashless transactions system. The concept is to establish a comprehensive ledger for a business or a person that records everything received and spent, and all of the assets held – mortgages, investment portfolios, debts, contractual financial obligations, and anything else of market value including pleasure boats, automobiles, and other machinery. There would be no need for cash because the ledger would tell you and anyone you were considering a transaction with how much is available and would be transactable at any specific moment. Any purchase, past or recent could be found and details provided whenever such information was sought. Governments would very much like such ledgers to exist because they could view everything that is taking place financially in real time, including ability to evaluate net worth, patterns of spending and of earned and unearned income, and of course, an instant assessment of all taxable activities. Governments would be able to gauge overall economic activity in real time, no longer needing to wait for months the collection of revenues and sales of businesses and surveys of consumer spending. This is not a dreamy idea. Blythe Masters, the JP Morgan architect of organized market trading of modern asset backed securities like mortgage backed securities and collateralized debt obligations, became known as one of the great financial engineers in recent decades. Widespread adoption of the trading techniques she devised led to an historic expansion of credit to households and great corporations alike. Subsequently she led innovations in trading of both commodities securities and physical commodities. In 2015 she is leading a new business effort to develop a universal cashless system. Not only is she gathering significant investor interest, but the Federal Reserve and various US Government agencies have become keenly interested in the potential usefulness and efficiencies of a universal cashless system. Needless to say, agencies concerned with illicit uses of cash or cash enabled means of tax evasion are enthusiastic. Estonia, a small country next to Russia with which I am personally familiar, essentially has a cashless economy. They use mobile phones to pay for almost all daily living requirements, including car parking, public transport, fuel, and in fact most of their daily purchases. This system does not yet include records of all personal assets, and especially personal gambling and other private activities. This hasn’t been developed here in the US yet, but one can envisage our government liking the idea. Some officials in the Eurozone have recently advocated the adoption of some kind of standardized, universal cashless system in which taxable revenues, personal income and wealth could not be hidden and taxation could be automated. No doubt there would be resistance in Greece to such a system because evasion of taxes has been the most popular national sport of all Greeks since before the Roman Empire spread to Greece. The people now intensively working on a mechanism for a cashless society are building it around the concept of blockchain technology. In essence, there would be a single ledger that records each expenditure or revenue event (the block), linking them chronologically with every other subsequent purchase, sale, or revenue event in a recorded chain. It could initially begin with a complete ledger of individuals or distinct businesses which could then be connected with another to a bigger ledger that a bank or other large financial institution might maintain for all of its clients. Banks or other designated financial institutions could then link their own comprehensive ledgers with those of the others. If you think about this for a moment, it is evident that the ledger for a big bank like JP Morgan would inevitably include activities throughout the world without respect for borders. Central banks and governments would inevitably encourage even further consolidation so that all significant financial flows and all debts and assets could be monitored in real time, enabling policies and regulations to be adapted to the realities of daily life. The objective of the blockchain that Blythe Masters is pursuing is ultimately to put together a global blockchain, which is consolidated at any moment in time. Everything you have and everything you owe are visible. In the blockchain system no entry can be altered or edited. No asset could be used for more than one transaction. No asset could be used twice for increased spending or investment leverage. Many investors might find this extremely uncomfortable, as it is common practice in banking and investment management circles around the world to use the same assets for re-collateralization. This process is known among bankers as rehypothecation. This would prevent the kind of securitization that many people say is taking place in China, where the same pile of metal ore sitting at the port can be used as collateral several times to borrow money from different banks and nonbank lenders. Nor could you do the kind of rehypothecation that is taking place in London, where the same assets are used to raise leverage by different entities, including banks and hedge funds. This was at the origin of the problems at MF Global for instance and it is quite significant. The British like to keep this system because it attracts a large flow of financial assets held around the world to be transferred to London and held in branches and subsidiaries of foreign financial institutions So we can understand why many governments and central banks don’t like this type of uncontrolled, highly leveraged activity. However, to turn it around, a single ledger for everybody would mean no more privacy, and the end of rehypothecation. We might also consider that if governments could see everything then various regulators would be enabled to issue guidance on what’s normal or appropriate personal and business behavior. If your funds are being used in a statistically abnormal manner then they can start routinely asking you for an explanation, if it was drug money or money laundering or purchases of regulated products like alcoholic beverages or firearms. If you were suspended for drunken driving authorities might like to add to the penalties the prohibition of purchasing or being in possession of an alcoholic beverage at any time during a probationary period. Bad dietary habits could also come under public scrutiny. Regulators motivated by moral self-justification can have boundless imagination in ways to compel proper behavior in society. So cashless, single ledger systems would raise everyone’s concerns about privacy and surveillance. Basically the government would be able to start questioning anyone vigorously about virtually every aspect of daily living. I can understand why they would want this, but it would be appalling for the rights of individuals. Looking at it the other way, cash is used by people for many things. It can be used for things like gambling, but it can also help Russian citizens who have opportunity to interact with foreign visitors to offset the decline of the ruble. In a sense it is refuge that can help individuals to deal with restrictive situations that are not the result of their own behavior. To me this is one of the essential pillars of individual liberties and flexibility. A complete ledger system would place everyone inside a precisely defined, monitorable box with defined set of rules of behavior. If local or national governments found themselves in financial crisis, they would not be limited to European style bail-ins of savings accounts. They could tap personal or family assets directly through the ledger system. Your balance could be altered by government simply by adding one new block to a long chain. One can understand the benefits, but there are potential negative consequences for individuals and businesses, and the Social Contract between citizens and their governments would be threatened. ET: The world has seen an explosion in debt levels since 2007, largely to combat the effects of the Great Financial Crisis, the aftershocks of which can still be felt to this day. Central banks played a crucial role in stabilizing banks and other large financial institutions, monetizing large amounts of government debt and privately held securitized debts in order to reduce borrowing costs and create liquidity to stave off deflation and recession. There are of course limits to this policy, in that economic agents – including the government – end up getting incentivized to borrow even more, thus increasing the inherent financial risks in our economies; shortages of good credit collateral and liquidity may inadvertently develop; and it tends to favor Wall Street more than Main Street, negating trickledown economics that should benefit all. What we can say conclusively is that recent policies are not working well, because the so-called recovery in the last seven years has been the weakest since WWII. Moreover, large asset holders have seen their wealth grow, while the majority of the working class have seen little gain, and in many cases have endured losses owing to loss of value in their homes, or even loss of ownership of their homes. In this context, it seems to us that using actual cash as a primary tool to inject liquidity into the economy has some merit. But this raises a more fundamental question. Rather than issuing debt, part of which would end up being monetized by the central bank under a QE program, the government could print more dollar bills and coins to be disbursed directly for payment of current social and infrastructure programs. Money might go straight to the real economy, rather than through the hands of bankers, without imposing interest charges and without issuance of new certificates of sovereign debt to add to already burgeoning national debt. Having been an economic adviser to several US Presidents, do you think this could be an effective economic policy tool, and as such should we be discussing it more often? HM: You raise a very interesting question about cash going into the real economy versus the banking system. Using actual cash to stimulate the economy is clearly an option. But let’s look at the Federal Reserve. It is really a government sanctioned institution that is owned by its member banks. The banks are eager to receive benefits from this system. The Chair of the Federal Reserve frequently reiterates that its primary objective is to ensure the safety and soundness of its banks. So you can understand why the US central bank would not want to send money outside of the system. It’s not part of its perceived responsibility to its members. You can have a government that could print the money without the central bank being involved, basically sending checks out to everyone. It has been done a few times in the past, with small checks issued by the Treasury Department and mailed to every registered taxpayer in hopes of boosting aggregate consumer spending. In these past experiments such disbursements to households primarily went to paying down debt, not to new purchases. So is the financial system we have in place today bad? I don’t think it is necessarily bad. The central bank wishes to retain some degree of control of the economy and many members of Congress are averse to anything that looks like a free subsidy to the populace. Of course, politicians are not always averse to complex subsidies that hide the reality of redistribution of government resources to specific interest groups like cotton, dairy and tobacco farmers, or to corn producers whose output is sold as ethanol additive to gasoline at a subsidized price. However, QE was intended to increase lending in the economy through the banks. Unfortunately, banks did not increase their lending, but instead diversified their other trading and investing activities, much of which took place globally as they diversified their businesses and their global presence. The main effect of artificially increased liquidity flowing through banks was to pump up the value of assets. People or companies who had them saw their wealth grow, but those who didn’t – which is most people – got relatively poorer as a result. In my view, QE has essentially widened the wealth gap between the poor people and the wealthy but it didn’t improve or help the broader economy. Worse, it encouraged companies to borrow money at near zero interest to buy back their own shares during recent years when revenues and earnings were not growing very much, thus giving the appearance of better quarterly results and higher stock valuations, and of course enhancing the wealth of business leaders and their directors, all of whom held shares. In the last seven years since the breakout of the Great Financial Crisis the world has experienced a real deficiency of capital flowing to new capacity, or productivity. The real economy was not expanded. Instead wealth was redistributed in the form of rising asset values, while wages and household incomes remained stagnant. Personally, I feel compelled to add my own opinion as an economist that QE was a failure in stimulating lending and economic growth in our advanced economies, and a failure by widening the wealth gap of our societies. The US administration might have accomplished something different via fiscal policy instead of having all these liquidity injections, but the President and Congress failed to devise a true package of economic growth stimulus. The Federal Reserve then took it upon itself to conjure up QE as an attempted substitute for the failures of Congress and the President. What we have learned is that monetary policy cannot be an effective substitute for meaningful fiscal policy. Indeed, a few decades from now people will most likely look back and view period this as one of the great economic mistakes in modern history. ET: Everyone talks about the lack of infrastructure investment in the US. Would it be better for the economy if the government had spent, say, $500 billion to pay for new infrastructure projects by printing $100 bills rather than more QE? HM: Yes. The increased fiscal flow into the economy would end up in the pockets of people involved in construction, maintenance and so forth – essentially into capital spending and consumption rather than into the stimulation of financial activities. ET: There is a real risk associated with this policy which is the government overdoing it. Once a politician gets unfettered access to a printing press there’s no stopping his or her programs getting funded. In theory debt has built-in features to keep the borrowers honest (which of late has been somewhat disabled by the central banks); however, with cash you can just print it to infinity – like in Zimbabwe, but most likely with the same consequences. Unconstrained money printing inevitably will result in inflation across all of society. Curiously, despite the benefits of cash in conducting economic activity, governments look at their citizens using cash with great suspicion. Some economists have recently begun to suggest that Western economies should ban it altogether as a way to avoid hoarding and promote private consumption growth – we suspect along the lines of what the FDR Administration did to gold in the 1930s [until then gold and silver had been used as currency in the US]. While this may seem far-fetched, Louisiana has banned cashed transactions on second hand purchases and several EU economies have prohibited cash purchases of items above a certain value. US citizens entering and leaving the United States must declare large amounts of cash they may be carrying, and there have been frequent seizures of such cash by government officials on the suspicion that large sums of cash are likely to be used for illicit activity or tax evasion. The reality now is that cash no longer flows freely through the economy. What it is your reaction to these events? HM: Things are a little different depending on the economy you are looking at. In Europe there’s a problem in that individual compliance with taxation rules is resisted. Wealth is often hidden so as to leave an impression of insufficient income or wealth. Governments across Europe introduced value added tax administration because it was a mechanism for automatically deducting consumption, or sales taxes at each step from raw materials to manufacture to distribution to final retail consumption. Value added taxes are automatically applied by cash registers and bookkeeping requirements. The idea of introducing value added taxes or some other form of consumption taxation has been discussed in Congress from time to time, but it has been vigorously opposed by Democrats as discriminatory towards lower income families. So this type of tax has been very useful especially in Southern Europe where not paying taxes has been a national privilege for decades, if not centuries. Still, there continue to be serious tax avoidance problems that tax authorities are trying to tackle. In Italy people using fancy cars and clothes at upscale ski resorts and beaches are closely monitored and audited to scrutinize sources of such extravagances. The case of Greece is even more extreme because it is almost impossible to collect taxes. The major source of income is tourism, and authorities are highly reluctant to resolve domestic tax deficiencies by piling taxes on tourists, which might result in diminished flow of visitors to Greece. So it is understandable that the authorities there would try to limit cash purchases to address this issue. In the US the situation is a little different. The banks would really like to have a means to hold or control title on everything. The Fed would like to have a more direct control of the economy and the IRS would like to have greater oversight. The motivation here is not deficiency of the economy but rather deficiency of governance. Taxation at the local or state level is much more issue-specific, including property taxes, licenses, mandatory fees for services, and so forth. I think the Fed is frustrated that QE has not resulted in higher levels of investment and growth, which is why they would like to have greater control of the economy, not less which is what would happen via the issuance of bills. ET: Looking at the broader picture, do you believe the dollar being the world’s reserve currency brings more net benefits or net costs to the US economy at this stage? HM: That’s a debate that has been going on for many decades and there are people on both sides. The economies of Asia and Europe are troubled, and emerging markets more broadly are in the downward phase of the economic cycle as a result of an historic slowdown of world trade. The primary driver of growth in those emerging markets is exports because domestic consumption is weak. When world trade was robust they had a strong boost to their economies which could not be achieved internally. But now their export demand has fallen off and domestic demand remains inadequate to drive a desired rate of economic growth. Plus we have Germany, France and the UK which are also very export dependent. As these economies weaken, we may see a liquidity crisis. In this environment, for example companies in Russia would rather own dollars than rubles. The Russian government is now trying to ban use of dollars or other foreign currencies, not for geopolitical reasons but because the Russian government and its central bank have an acute shortage of dollars that is continuously worsening as world demand for Russian resources continues declining. Beside the US Dollar, the other most liquid currencies are Sterling and the Japanese Yen. Sterling actually has the peculiar feature that mobile money in the world likes to go to London. It is a nice place to live close to Continental Europe, a big financial center and the courts protect the rights of asset holders. In Japan the government is so involved in the yen through its vast government managed or regulated pension and savings system that market liquidity remains strong even though Japan’s financial markets suffer ups and downs. When world markets suffer a downturn, Japanese investors are quick to repatriate wealth held abroad, keeping the Yen stronger than it might otherwise be. The US economy has weaknesses, but it also is far more resilient than most other economies around the world. The US financial markets have far larger liquidity than any other market in the world, so holding assets denominated in dollars assures that buyers and sellers will be available at times of declining financial confidence. If emerging markets continue in their downward trajectory or if anything goes wrong elsewhere, particularly in China, there would likely be an increase in demand for dollars primarily because it is the most liquid alternative asset. Even if we had a downturn in this market there would be global demand for dollar assets – just to park anywhere in the US because the expectation would be that the dollar would be rising in relation to other currencies. So this money inflow can go into stocks, bonds and real estate. And this will benefit the US in the event of a global recession. If there is one, the US would probably be the first to recover and it would be because of this liquidity provided by the dollar. I can see why people say that the dollar is costly, but for now and in the next few years it will be hugely beneficial to the US. And I cannot see the dollar collapsing any time soon. The Chinese are increasingly using their currency in international transactions. But if you look closely the other countries with which China is now trading have no money, so they can either barter or use the Chinese currency system. The wealthy Chinese park as much money in dollars as they can, which is why capital flight from China is huge and growing. Chinese capital flees to the US in various forms. For example, they send their kids to study here and before graduating they set up businesses which are then capitalized by their wealthy parents, enabling the kids to get “green cards” or residency permits. I hear that most Chinese juniors in the US are told by their parents not to return home. And millions of dollars are coming in to buy real estate and other assets put under the supervision of sons, daughters, and other relatives. So the dollar is a good thing to have for the next several years. And it’s hugely beneficial to us during times of global slowdown. By the way, negotiating the emergence of an alternative to the dollar would take a decade or more, and it would be really painful. It’s nothing that can happen at the snap of a finger. I don’t see it any time soon; something for the next century perhaps. ET: But if the US were to ban the use of dollar bills, would this not mean the certain demise of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency? After all foreigners hold an estimated 70% of all US dollar currency and would dump it in a hurry if it were banned, in exchange for some other currency, likely from a major US economic rival. HM: I think that’s right. It would not be painless for us. A lot of this money is what we used to call some years ago “hot money”. So the question is where would it go? And that’s not an easy question to answer. A lot of people say well it’s going to go to gold. I have had many discussions about this with traditional gold traders in Europe, where there is gold trading experience going back centuries. Their view is that you can take some gold home, but if you are talking millions or even billions then you have a problem. You can only move that much money if you use an armored vehicle and strong guards to move heavy gold caches. And given that you will want to see and touch it, if you store it in your basement people will eventually discover you have it and try to steal it. If you leave your gold in a bank, the bank will seize it and use it if the bank falls into distress, perhaps leaving you a promissory note. Basically gold is heavy, not secure enough for holding by individuals, and not easily moved. So where do you go then? If there is another highly liquid alternative then OK. If the Eurozone were healthy maybe the Euro would be a possibility, or you might park in Sterling for a while. Would there be a creation of something else? Maybe if such a scenario unfolds in the future, but this would likely be a creation of private interests and not governments, and which in fact would be used to usurp the power of governments. In the UK we can see emerging experiments with locally issued scrip as currency substitutes, usable among agreed parties. That particular experiment seems to be growing in scale this year. ET: Prof. Malmgren, it has been a real pleasure talking with you. Thank you very much for sharing your insights with us. HM: Thank you. |

|||||||||||

Submitted by Bill Bonner via Bonner & Partners (annotated by Acting-Man's Pater Tenebrarum),

|

|||||||||||

Submitted by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com, The Danger Of Eliminating CashIn the early days of central banking, one primary objective of the new system was to take ownership of the public's gold, so that in a crisis the public would be unable to withdraw it. Gold was to be replaced by fiat cash which could be issued by the central bank at will. This removed from the public the power to bring a bank down by withdrawing their property. A primary, if unspoken, objective of modern central banking is to do the same with fiat cash itself. There are of course other reasons for this course of action. Governments insist that they need to be able to trace all private sector transactions to ensure that criminals do not pursue illegal activities outside the banking system, and that tax is not evaded. For the government, knowledge of everything individuals do is necessary control. However, in the monetary sense, anti-money laundering and tax evasion are not the principal concern.Central banks are fully aware that the financial system is fragile and could face a new crisis at any time. That's why cash in their view must be phased out. A gold run against a bank or banks, in the ordinary course of banking, is no longer a systemic threat, but the possibility that depositors might queue up to withdraw physical cash from a bank in which they have lost confidence is very real. Furthermore it is a public spectacle associated with monetary disorder of the most alarming sort. It is far better, from a central banker's point of view, to only permit the withdrawal of a deposit to be matched by a redeposit in another bank. That way, a bank run can be hidden through the money markets, with or without the intervention of the central bank, and the deflationary effects of cash hoarding are avoided. This is commonly understood by followers of monetary matters. What has not been addressed properly is how a cashless economy behaves in the event of a significant alteration in the public's preferences for money relative to goods. Normally, there is a balance in these matters, with the large majority of consumers unconcerned about the objective exchange-value of their money. There are a number of factors that can change this complacent view, but the one that concerns us for the purpose of this article is the speed at which the relationship between the expansion of money and credit and the prices of goods and services can change. There is no mechanical link between the two, but we can sensibly posit that the extra demand represented by an increase in the money quantity will eventually drive up prices, setting the conditions for a potential shift in public preferences for money, which would drive prices up even more. When the general public perceives that prices are rising and will continue to do so, people will buy in advance of their needs, increasing their preference for goods over holding money. This is currently desired by central bankers wishing to stimulate demand, but they are under the illusion it is a controllable process. Furthermore, increases in the money quantity are being driven by factors not under the direct control of monetary authorities. Welfare states are themselves insolvent and require the issuance of money and low-interest credit to balance their books. Commercial banks can only continue in business if the purchasing power of money continues to fall, because their customers are over-indebted. Unless the expansion of the money quantity continues at an increasing rate, the whole financial system will most likely grind to a halt. It is now required of central banks to ensure the money quantity continues to expand sufficiently to prevent systemic failure. It is therefore only a matter of time, so long as current monetary policies persist, before it dawns on the wider public what is happening to money. Preferences will then shift more definitely against holding money, radically altering all price relationships. If this leads into a hyperinflation of prices, which is the logical and unavoidable outcome, the speed at which money collapses will be governed in part by physical factors. In the case of Germany's great inflation in the 1920s, the final collapse can be tied down to a period of six months or so, between May and November in 1923, after a last-ditch attempt to control monetary inflation failed. The limiting factor in this case was the time taken to clear payments through the banking system, and when prices began to rise so rapidly that cheques lost significant value during the clearing and encashment process, the economy moved entirely to cash. When prices rose faster than cash could be printed, the limitation on the purchase of necessities then became one of cash availability. It is in truth impossible to isolate all the factors involved, and the course of events during the destruction of a currency's purchasing power is bound to vary from case to case. Today the situation is very different from the hyperinflations in Europe over ninety years ago. A society which uses electronic transfers spends bank deposits instantly. The merchant, who is subject to the same panic over the value of the payment received looks to dispose of his cash balances as rapidly as possible as well. In other words, the electronic transfer of money has the potential to facilitate a collapse in purchasing power at a rate that is far more rapid than previously experienced. The most obvious delaying factor left becomes the speed with which the public realises that government money has no value at all. People are generally ignorant of monetary matters, and a majority of them have no alternative but to believe in their money, because without it they are reduced to barter. It is entirely human to wish these concerns away. For a minority of the population lucky enough to have a combination of wealth and foreign currency bank accounts the problem was not so great in the past, but the interconnectedness of the global monetary system suggests that all today's fiat currencies face the same problem contemporaneously, and there is no refuge in foreign currency. These concerns have encouraged the development of alternative solutions, such as our own Bitgold/GoldMoney payment and storage facility, which will allow both consumers and producers to reduce their exposure to the banking system and continue to trade. There are also private currency alternatives such as bitcoin. Whether or not alternative currencies have a future monetary role for ordinary people at this stage looks unlikely, primarily because they are less stable than government currencies; however that might change in the future. They represent a work-in-progress that has the power to undermine the state monopoly on money, not least because they lie outside a government's ability to manage capital controls directed through the banks. What fascinates many of those with an understanding of anticipatory private sector solutions, is the potential for triggering a seismic change in the money used today. They have the ultimate potential to free commerce from the whole concept of a state-directed monetary policy. Rapidly developing technological solutions are therefore another factor that could accelerate the public rejection of government money and the state-licensed banking system, simply by offering a practical alternative to a debasing currency. With the progress being made to eliminate cash and the private sector's ability to develop an alternative financial system in advance, if the collapse of government money comes, it could be very swift indeed.

|

|||||||||||

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - August 23rd, 2015 - August 29th, 2015 | |||||||||||

| BOND BUBBLE | 1 | ||||||||||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 2 | ||||||||||

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | 3 | ||||||||||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 4 | ||||||||||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 5 | ||||||||||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

6 |

||||||||||

| TO TOP | |||||||||||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||||||||||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||||||||||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||||||||||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||||||||||

| Market | |||||||||||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||||||||||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||||||||||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||||||||||

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||||||||||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

||||||||

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|||||||||

|

2013 2014 |

|||||||||||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||||||||||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||||||||||

I - POLITICAL |

|||||||||||

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | THEME | ||||||||||

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|||||||||

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | |||||||||

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | |||||||||

II-ECONOMIC |

|||||||||||

| GLOBAL RISK | |||||||||||

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | |||||||||

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | |||||||||

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | |||||||||

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | |||||||||||

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

|||||||||

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

||||||||

III-FINANCIAL |

|||||||||||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |||||||||

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | THEME | ||||||||||

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | |||||||||

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||||||||||

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||||||||||

|

SII | ||||||||||

|

SII | ||||||||||

|

SII | ||||||||||

|

SII | ||||||||||

| TO TOP | |||||||||||

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP