|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

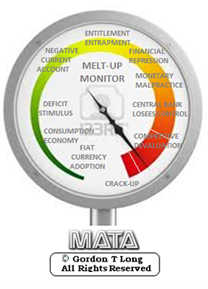

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

�

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros � |

�

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

��

"Currency Wars "

|

�

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

�

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT :� ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

�

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

�

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

�

�

Wed. Sept 16th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

onTWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

�

�

ANNUAL THESIS PAPERS

FREE (With Password)

THESIS 2010-Extended & Pretend

THESIS 2011-Currency Wars

THESIS 2012-Financial Repression

THESIS 2013-Statism

THESIS 2014-Globalization Trap

THESIS 2015-Fiduciary Failure

NEWS DEVELOPMENT UPDATES:

FINANCIAL REPRESSION

FIDUCIARY FAILURE

WHAT WE ARE RESEARCHING

2015 THEMES

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY

PENSION POVERITY

WAR ON CASH

ECHO BOOM

PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX

FLOWS - LIQUIDITY, CREDIT & DEBT

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

- COMING NWO

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING

(A) Active, (C) Closed

MATA

Q3 '15- Chinese Market Crash

(A)

Q3 '15-

GMTP

Q3 '15- Greek Negotiations

(A)

Q3 '15- Puerto Rico Bond Default

MMC

OUR STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS (SII)

NEGATIVE-US RETAIL

NEGATIVE-ENERGY SECTOR

NEGATIVE-YEN

NEGATIVE-EURYEN

NEGATIVE-MONOLINES

POSITIVE-US DOLLAR

| � | � | � | � | � |

ARCHIVES�

| SEPTEMBER | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| � | � | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | � | � | � |

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| � |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| � |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| � |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic | 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

�

Reading the right books?

No Time?We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

�

�

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

�

�

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

� | � | Theme Groupings |

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

� |

|||

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY � |

� | � | � |

Submitted by�Tyler Durden�on 09/15/2015 18:01

WTO's Stark Warning On Global Trade: "The Timing Belt On The Global Growth Engine Is Off"One narrative we’ve built on this year is that the subpar character of the global economic recovery isn’t just a consequence of a transient downturn in demand from China whose transition from an investment-led, smokestack economy towards a model driven by consumption and services has effectively caused the engine of global growth to stall. Rather, it seems entirely possible that an epochal shift has taken place in the post-crisis world and the downturn in global trade which many had assumed was merely cyclical, may in fact be structural and endemic.� We touched on this in “Emerging Market Mayhem: Gross Warns Of ‘Debacle’ As Currencies, Bonds Collapse,” when we highlighted a�WSJ piece that contained�the following rather disconcerting passage:�“Central to this emerging-market slump is the unprecedented weakness of world trade, which has now grown by less than global output for the past four years, unique since World War II.” This echoes concerns we voiced in May, when�BofAML was out warning�that if “wobbling” global trade turned out to be structural rather than cyclical, “then EM economies should not count on meaningful demand boosts coming from above-trend growth in DM.” Most recently, we�looked at�freight rates (which, incidentally, Goldman�predicted earlier this year�will remain subdued until 2020) noting that despite a dead cat bounce in the Baltic Dry, “freight rates on the world’s busiest shipping route have tanked this year due to overcapacity in available vessels and sluggish demand for transported goods. Rates generally deemed profitable for shipping companies on the route are at about US$800-US$1,000 per TEU.�In other words, at current prices shippers are losing half a dollar on every booked contractual dollar at current rates.” Now,�WSJ is back with a fresh look�at the new normal for global trade and unsurprisingly, the picture they paint based largely on WTO data and projections, is not pretty. Here’s more:

And this, bear in mind, is the environment into which the Fed intends to hike, even as the emerging economies which have been hit the hardest by the slowdown in trade (which has served to depress commodities and wreak havoc on commodity currencies) would likely suffer from accelerated capital outflows in the wake of an FOMC liftoff.� What's also notable here is that this comes as central banks have engaged in round after round of easing in a desperate, multi-trillion quest to boost global growth, suggesting that competitive devaluations are a zero sum game and to the extent that individual countries can boost exports in the short term by devaluing, that gain comes at someone else's expense, meaning, in The Journal's words, "foreign-exchange moves have little chance of raising trade overall" and even if they did, the backdrop of depressed demand means that what many EMs are producing, no one now wants, irrespective of how cheap it may be. Make no mistake, the most worrying part of the new normal for trade is what it portends for emerging markets. We've already seen Brazil's investment grade rating cut by S&P as the country careens headlong into fiscal, political, and economic crises. As Morgan Stanley put it in August, Brazil is the epicenter and one can reasonably expect that other EMs will follow in its footsteps should the WTO's projections about the sturctural nature of depressed global demand and trade prove accurate. What comes next is the descent of the emerging world into frontier status, and as we've put it on several occasions, after that it will be time to break out the humanitarian aid packages. Of course, as we mentioned late last month,�there is one more possibility: central banks could learn how to print trade.� |

|||

Submitted by�Tyler Durden�on 09/15/2015

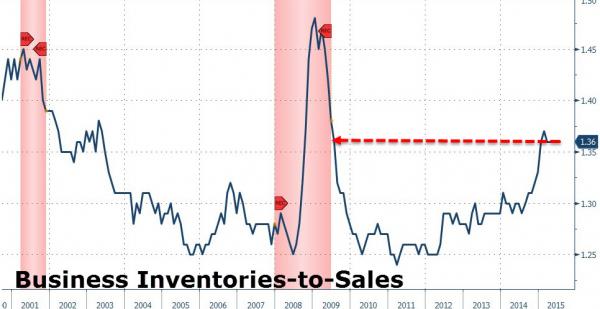

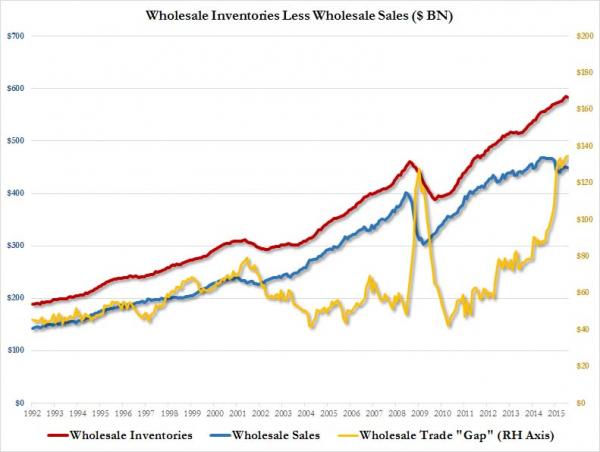

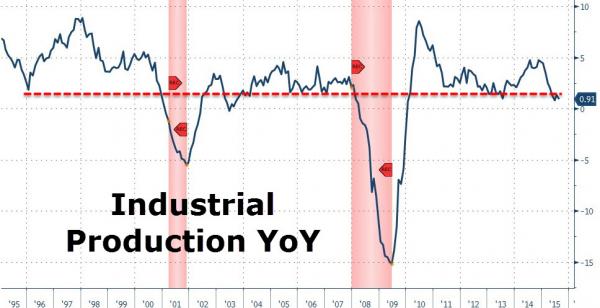

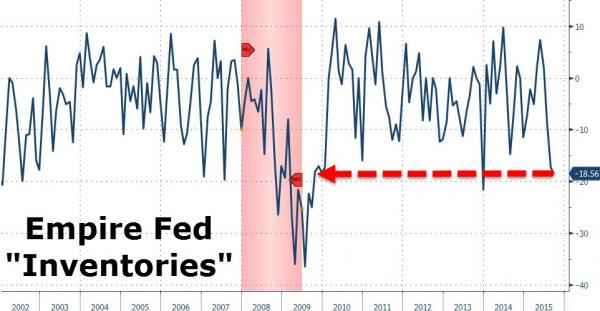

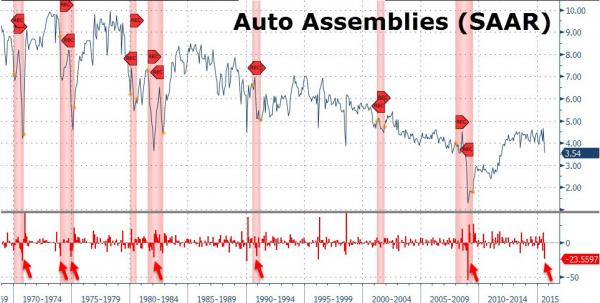

Destroying The "There Are No Signs Of An Imminent Recession" Meme In 4 ChartDay after day investors are treated to 5-Star Morningstar managers, so-called "strategists", economissseds with entire religions on the line, and circus barkers who proclaim that:�a) The US is decoupled from the rest of the world; and/or b) The US is the cleanest dirty shirt; an/or c) There are no indications that the US economy is near a recession.�Here are four simple charts - from, just today's data - that destroy this glass half full and rose-colored ignorance of reality... 1) Business Inventories-to-Sales are at recesssion-inducing levels... 1a) Sidenote 1 - Wholesale Inventories relative to sales have NEVER been higher... 1b) Sidenote 2 - here is why that is a problem... 2) Industrial Production is - as would expeted given the inventories - rolling over into recession territory... 2a) Sidenote - as Empire Fed confirmed this morning for August - inventories are collapsing (and along with that Q3 GDP)... 3) Retail Sales is not supportive of anything but a looming recession... And finally, 4) The last 6 times Auto Assemblies collapsed at this rate, the US was in recession... So - still think The US is "safe" - because stocks are certainly not priced for anything other than a hockey-stick of hope in earnings rebounds, let alone a collapse into recession. |

|||

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK -Sept 13th, 2015 - Sept. 19th, 2015 | � | � | � |

| BOND BUBBLE | � | � | 1 |

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | � | � | 2 |

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | � | � | 3 |

| CHINA BUBBLE | � | � | 4 |

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | � | � | 5 |

EU BANKING CRISIS |

� | � | 6 |

| � | � | � | 16 - Credit Contraction II |

ALL EYES ON CREDIT

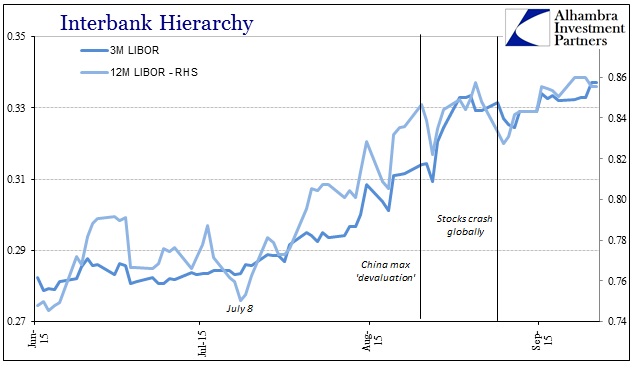

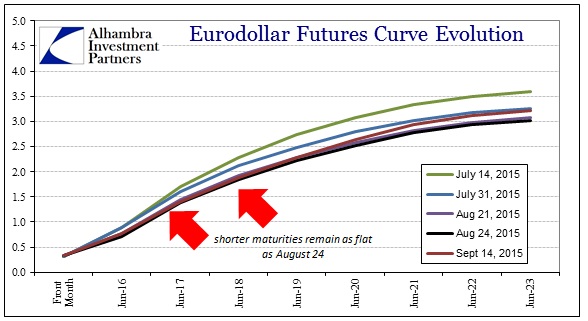

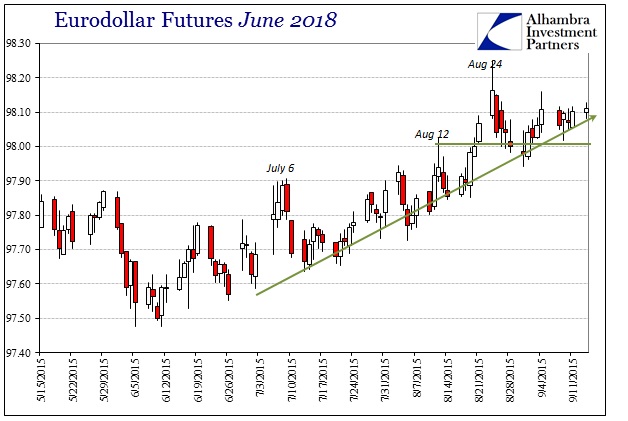

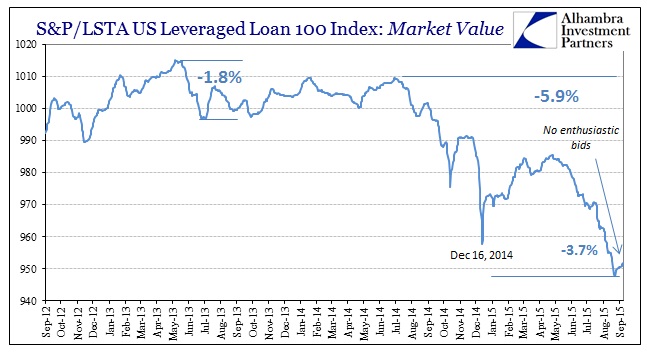

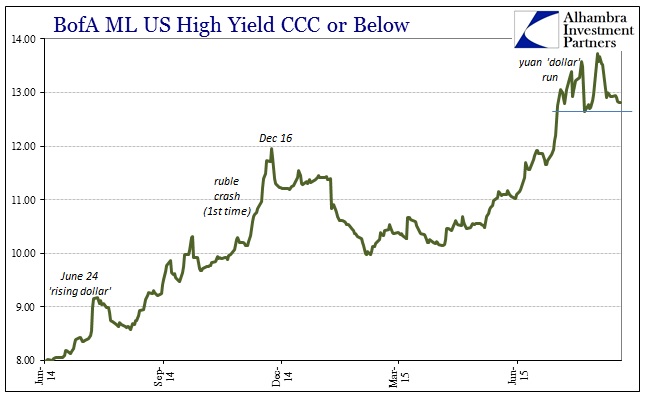

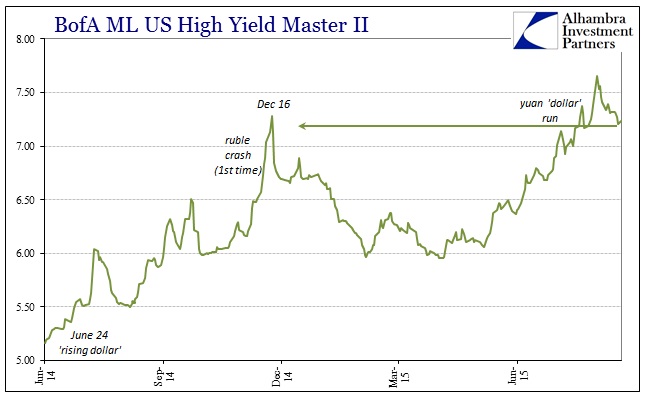

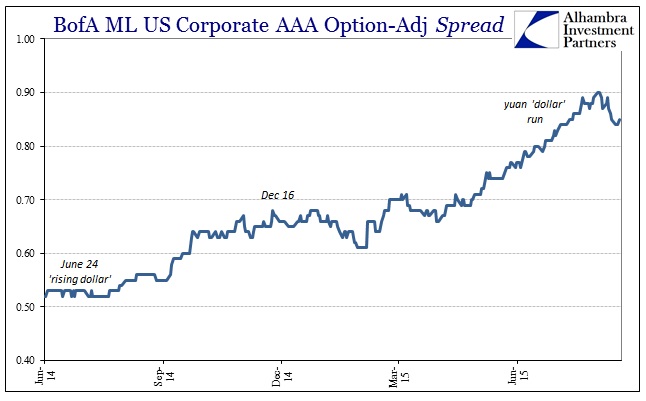

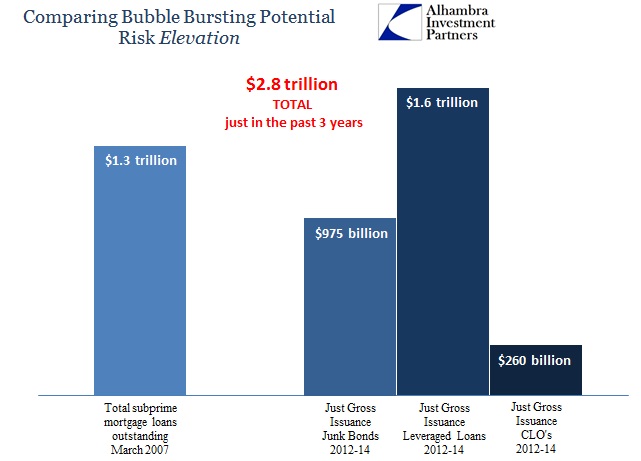

Awaiting The Spark?Alhambra Investment Partners The new week opens much the same as last week traded, with narrow ranges abounding in risky asset prices. From leveraged loans to junk debt, funding markets continue to run the correlations. From this “dollar” view, the lack of “buying” interest in the corporate bubble, bargain value or not, may more properly be understood as lack of “funding” interest. On that point, as noted earlier today, banks are the only aspect to really consider as both the near-term acceleration and long-term decaying structure. From unsecured eurodollars (LIBOR) to eurodollar futures, the funding market structure remains unkind toward assuming risk again. There is an uncomfortable closeness to the worst parts around August 24 that more than suggests an almost uniform aversion; data and events since then haven’t exactly been reassuring (and not just China), so there is, for once, some sanity and sense here (another indication of how much the cycle has turned already). While 12-month LIBOR has been the been the primary mover since December, it is really 3-month LIBOR that I think is perhaps the focal point or central axis of (il)liquidity. Friday’s read of 33.72 bps is the highest since October 2012 just before the first MBS trades on QE3 settled. In eurodollars, the curve inside of 2020 remains largely the same as its flatness of August 24. Given that the outer maturities have steepened that portion, it is significant that the “money part” of the curve (where about $10 trillion in open interest is traded and held) refuses to budge no matter the do’s and don’ts of this week’s FOMC melodrama. The funding view seems quite proportional to the corporate bubble pricing regime. On the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan 100, the market value index remains barely above 950, not really much different than the August 26 low of 947.85. The rest of the junk bond pricing views are similarly depressed to differing degrees. As mentioned last week, the primary problem here is time. August 24 was three weeks ago and it is increasingly clear that nothing was settled by the liquidations and disruptions. That possibility threatens to turn what might have been temporary adjustments in not just risky positions themselves but open and easily offered leverage into a more permanent and structural shift. Obviously, that has been the case going back to last year’s “dollar” turn and even to the high point in the junk credit cycle in May 2013. But as each of these individual “events” fail to find a durable point of stability (like even a potential bottom) and the downside momentum only accelerates with each, the risk systemically becomes more about the size of the exits than whether they would actually become necessary. The fact that outward liquidity and prices seem so very linked in the aftermath suggests we may have already arrived at that point and that institutional positions remain far more than wary of it. The real downside is where those two points intersect; funding contracts further, narrowing the exits, while the volume of those reaching for them at the same time increases exponentially into a self-reinforcing spiral. It is very much like two massive armies having already been mobilized staring directly at each other awaiting only a small spark to set “it” off. � |

|||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � |

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � |

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | � | � | � |

| � | � | � | |

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET | � |

� | � |

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � |

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � |

| � | � | � | |

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

FINANCIAL REPRESSION

JAMES BIANCO THE FED'S PLAN FOR INTEREST RATES Bianco research started in 1998 and is affiliated with Arbor research and training. It is an independent research company with James Bianco as its president. �Bianco research specializes in macro, fixed income and equity research. James views financial repression in light of what Ben Bernake said in his November 12 op-ed in the Washington post: ”the purpose of QE2 is the fed buys bonds, force down interest rates, that would make them relatively unattractive for most bond investors, seeking alternatives they would move further out the risk curve and they would not buy .They would push up those assets prices, create a wealth effect expecting a cycle in which the wealth effect creates economic growth to justify those higher prices”. The forced down interest rate will not bode well for individuals who need certain rates of return to guarantee things like pension and retirement. You end up taking more risk by buying riskier assets which pushes up its price causing you to feel wealthier. He explains that when a government body in this case the CBN steps in and sets price at levels where they would not ordinarily go by themselves, they are repressing the price of interest rate, inflating the price of risk assets. They argue it is a greater good because of the wealth effect that comes from that. James doesn’t think that the wealth effect occurs as a result of that. According to him, Milton Friedman in 1915 developed the permanent income hypothesis which states that if an asset goes up in price for example a house, you treat it as another form of permanent income. One the other hand, if your stock portfolio goes up, you perceive as temporary due to what you read in the paper. “That’s why we obsess over the fed because we think all this stuff is temporary and we want to find out how temporary it is, because when the fed raises rates… I guess to mix my metaphors a little bit with the old warren buffets’ old line that we find out that we are swimming naked when the tide goes out”.

“There are two things to keep in mind concerning what the feds will do. There’s the economic data and the market pricing of it”. He says that based on the economic data, the fed has set up some parameters for itself and from a data dependent point of view, they have everything they need, but James believes that what will hold back the feds will be market instability. Currently, there is a great deal of volatility and uncertainty in the Chinese and emerging markets. He believes the instability in these markets will cause the feds will to maintain interest rates because they are hoping that things would calm down enough by Dec. He mentions that part of the reason for the unstable markets is due to the Feds insistence on raising rates. EU On his view of the EU, James Bianco has this to say: “The history of the Europe is for the last thousand years is every generation they try to kill each other and the last one was in World War 2”. Then they decided to get closer in order to prevent more wars. This led them to create the euro. According to him, the problem with the euro, is that you have 17 different countries in different cycles using the same currencies. He says that Draghi’s plan is to get interest rates to below zero and continue trying to stimulate the economy. He goes further to explain that the current refugee crisis that the EU is facing will have a huge negative impact on their economy. He doesn’t think Draghi’s plan will work because people think it’s temporal and as long as they think that, the permanent income hypothesis will take effect. Check out his interview with Gordon T Long which covers this and much more. �

|

09-14-15 | THESIS | |

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| � | � | ||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

� | � | � |

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | � | THEME | � |

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

� | THEME |  |

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | � |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | � |

II-ECONOMIC |

� | � | � |

| GLOBAL RISK | � | � | � |

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | � |

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | � |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | � |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | � | � | � |

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | � | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

III-FINANCIAL |

� | � | � |

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | � | THEME | � |

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | � |

| GENERAL INTEREST | � |

� | � |

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

� � � |

� | SII | |

| TO TOP | |||

| � | |||

�

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

���

���

TO TOP

�

�

�

�

�� TO TOP

�

�