|

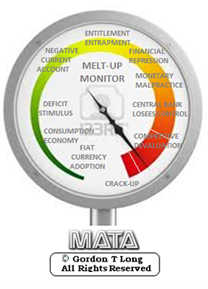

�MELT-UPMONITORMeltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013 � NEW SERIES RELEASE Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros � NOW SHOWING � � � HELD OVER MONETARY MALPRACTICE MONETARY MALPRACTICE: Deceptions, Distortions and Delusions MONETARY MALPRACTICE: Moral Malady MONETARY MALPRACTICE: Dysfunctional Markets � � � � � JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Currency Wars "

|

�

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

�

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT :� ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

�

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

�

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

�

�

�

�

Fri. Jan. 17th, 2014

MACRO WATCH Q1 2014

NOW AVAILABLE - SUBSCRIBE

�

�

�

| � | � | � | � | � |

| JANUARY | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| � | � | � | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | � |

| �� Complete Archives � |

||||||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1 - Risk Reversal |

| 2 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 3- Bond Bubble |

| 4- EU Banking Crisis |

| 5- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 6 - China Hard Landing |

| � |

| 7 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 8 - Geo-Political Event |

| 9 - Global Governance Failure |

| 10 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 11 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 12 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 15 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 16 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 17 - Credit Contraction II |

| 18- State & Local Government |

| 19 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| � |

| 20 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 21 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 22 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 23 - US Reserve Currency |

| 24 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 25 - Oil Price Pressures | 26 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 27 - Food Price Pressures |

| 28 - Global Output Gap |

| 29 - Corruption |

| 30 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| � |

| 31 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 32- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - US Reserve Currency |

| 35- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 36 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 37 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 38 - Terrorist Event |

| 39 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

| 41 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

�

Reading the right books?

No Time?

![]()

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers!

![]()

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

�

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

| THIS WEEKS TIPPING POINTS | MACRO NEWS | MARKET | 2013 THEMES |

�

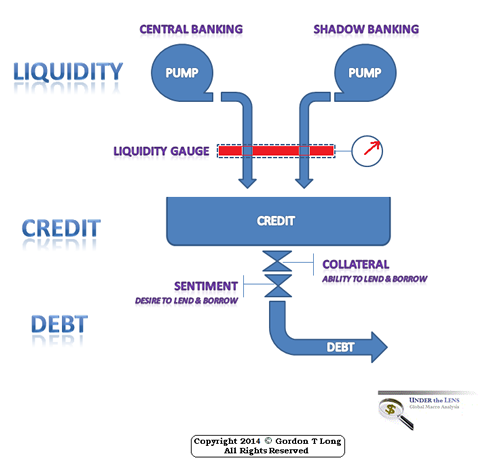

FLOWS: Liquidity, Credit and Debt

�

We have now strategically added

Richard Duncan's "Liquidity Gauge"

�

�

"BEST OF THE WEEK " |

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags | TIPPING POINT or 2013 THESIS THEME | |||

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

� | � | Theme Groupings |

|||

| � | � | � | ||||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

� | � | � | |||

|

FLOWS: Liquidity, Credit and Debt � We have now strategically added Richard Duncan's "Liquidity Gauge" to MATA FLOWS � |

� | � | ||||

FLOWS - Global Deflation THE GLOBAL DEFLATION THREAT "Here’s the bottom line. You are going to hear a lot of talk about Fed tapering. And, sometime between now and March, the Fed will begin to reduce the amount of money it creates each month. This could cause the stock markets around the world to have a significant correction. My suggestion is to be prepared for a selloff, but don’t panic. There is a very big difference between tapering QE and ending QE. I believe the Fed will have to continue printing more than $500 billion during both 2014 and 2015 in order to continue pushing up asset prices. At this point, only higher asset prices will make the US economy grow and only higher asset prices will stave off deflation."

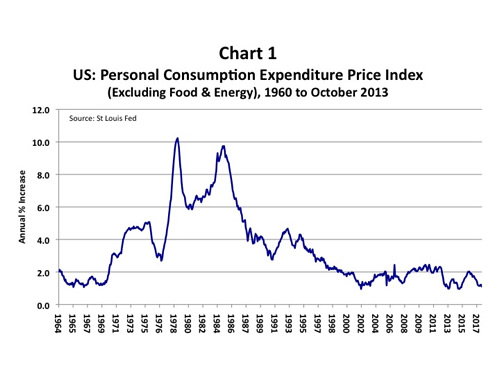

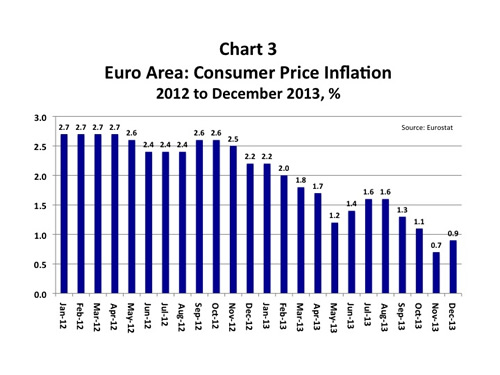

Today, I will discuss how the risk of deflation will influence the Fed’s decision-making process over the next few years. Chart 1 shows the Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (excluding Food & Energy), otherwise known as the Core PCE Index. It is the inflation index for the United States that the Fed monitors most closely. In October 2013 (the most recent data available), the index was up only 1.1% compared with one year earlier. The rate of inflation has been lower than this during only eight months since records began in 1960. Moreover, as you can see in the chart, the recent trend is downward, suggesting the possibility of even more disinflation in the US during the months ahead. Keep in mind that this weakness in US consumer prices is occurring even though the Fed is creating $85 billion a month and pumping it into the economy. I’ll come back to the US in a moment, but first consider Japan (Chart 2) and the Euro Area (Chart 3). As you can see in Chart 2, consumer prices in Japan began falling in 1995. Since then, the country has experienced deflation during 12 out of the last 19 years. This year the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is expected to rise by 0.5%. However, the Japanese Central Bank is printing money much more aggressively than even the Fed. The US central bank is currently printing new money roughly equivalent to 6% of US GDP per year, while the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is printing something closer to 18% of Japan’s GDP. Given that scale of fiat money creation, it is very surprising that inflation in Japan is still barely positive. Finally, consider the Euro Area, shown in Chart 3. The European Central Bank (ECB) is not creating fiat money through a program of Quantitative Easing, as are the Fed and the BOJ. But, in light of the pronounced downward trend in consumer price inflation during 2013, they have begun to consider it. The ECB’s key policy interest rate was cut from 0.5% to 0.25% in November; and ECB Governor Draghi has made it clear that the ECB has numerous policy tools it could employ, if necessary, to insure price stability. Against this background of global disinflation, it is unlikely that the Fed will be able to stop printing money any time soon. Here’s why. There are three kinds of inflation:

As we saw in Chart 1, consumer price inflation excluding food and energy in the US has rarely been lower than it is now. Commodity prices are�falling�sharply. The high commodity prices of a few years ago have resulted in a surge of new supply for many types of commodities; and that new supply is driving prices down. The Jefferies CRB Commodity Price Index has dropped 25% since mid-2011. Asset prices, on the other hand, are inflating sharply. The reason they are inflating is because the Fed is printing money and using it to acquire assets. The S&P 500 stock index is up 25% this year and US home prices have risen by 13% over the past 12 months. This increase in asset prices has driven up the “Net Worth” of the household sector by 11% over the past year to $77 trillion, creating a wealth effect that has allowed those Americans who own assets to spend more. Their spending has added to aggregate demand. Without the increase in aggregate demand brought about by QE and its impact on asset prices, the United States would most probably be experiencing deflation now. If the Fed ends QE altogether, asset prices will fall and aggregate demand will fall. Then, the chances are high that consumer prices will fall as well. Falling prices make it very difficult for people and businesses to repay their debts. That increases the danger that the economy will spiral into a debt-deflation depression. Deflation is the Fed’s worst nightmare. So, here’s the bottom line. You are going to hear a lot of talk about Fed tapering. And, sometime between now and March, the Fed will begin to reduce the amount of money it creates each month. This could cause the stock markets around the world to have a significant correction. My suggestion is to be prepared for a selloff, but don’t panic. There is a very big difference between tapering QE and ending QE. I believe the Fed will have to continue printing more than $500 billion during both 2014 and 2015 in order to continue pushing up asset prices. At this point, only higher asset prices will make the US economy grow and only higher asset prices will stave off deflation. The Fed will have to continue printing more than $500 billion during both 2014 and 2015 in order to continue pushing up asset prices. At this point, only higher asset prices will make the US economy grow and only higher asset prices will stave off deflation.

Richard Duncan was a consultant to the IMF in Thailand during the Asian Crisis, worked for the World Bank in Washington and was head of Global Investment Strategy for ABN AMRO in London. Few in the world are better qualified to decipher Global Liquidity and Credit FLOWS than Richard Duncan. |

� | � | MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - January 11th - January 18th | � | � | � |

| RISK REVERSAL | � | � | 1 | |||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | � | � | 2 | |||

| BOND BUBBLE | � | � | 3 | |||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

� | � | 4 |

|||

| SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS [Euope Crisis Tracker] | � | � | 5 | |||

| CHINA BUBBLE | � | � | 6 | |||

| TO TOP | ||||||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | ||||||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � | |||

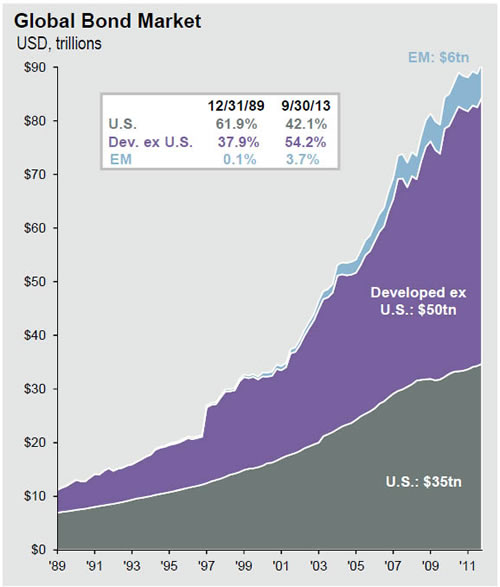

EVENTUALLY ALL THIS HAS TO BE ROLLED OVER Rates Will Have to Be Attractive Enough!

|

01-14-14 | � | � | |||

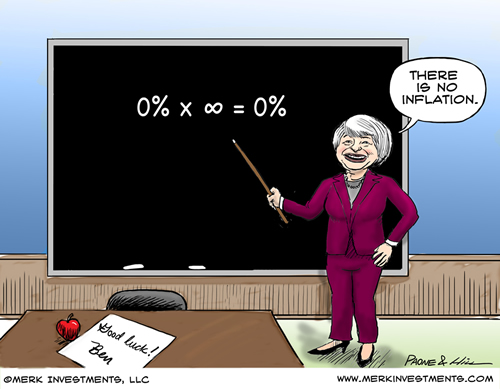

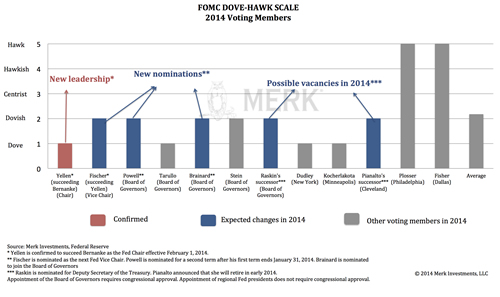

MONETARY POLICY - Dollar, Currency & Gold Outlook Merk 2014 Dollar, Currency & Gold Outlook 01-14-14 Axel Merk, Merk Investments Nothing normal about U.S. monetary policy During her confirmation hearings, incoming Fed Chair Janet Yellen testified that U.S. monetary policy is to revert towards more traditional monetary policy once the economy is back to normal. With due respect, in our assessment, that’s an oxymoron. In a “normal” economy capital is allocated according to the risk profile of the project under consideration. However, when the Fed actively distorts the price discovery mechanism with its QE programs, we believe it is impossible to move back to a normal economy. Inflation promise? The Fed has told the market in no uncertain terms that it is in no rush to raise rates. Outgoing Fed Chair Bernanke often argued one of the biggest policy mistakes during the Great Depression was to raise rates too early. Trouble is, removing stimulus might allow deflationary forces to take over once again, negating the “progress” that’s been made with cheap money. We interpret that to mean the Fed has all but promised to err on the side of inflation. Yellen is said to favor a rules-based approach to setting policy rates. In theory, that’s laudable, except that Yellen in particular appears to prefer “rules” that heavily discount inflation indicators in favor of employment indicators. Hawkish Fed? Do Pigs Fly? There is a bewildering opinion shaping that a Yellen Fed will be hawkish, especially since former Bank of Israel (BoI) Governor Stanley Fischer has been nominated to become Vice Chair. Already rumors are creeping up that uber-hawk Tom Hoenig will join the team. Let’s get a few things straight:

Taper? Anyone? Let’s look across the border to get a better assessment of what all this taper talk is all about. Unlike the taper rhetoric, the practice has looked a little different. Please consider the change in central bank balance sheets across the biggest central banks:

While central bank balance sheets for the biggest countries have been indicative of currency moves, there are limits as to what these charts show. Notably, the Swedish central bank a few months ago, as well as the Reserve Bank of Australia just recently have shown a spike in the size of their balance sheets. These movements have less to do with monetary policy than to changes in regulations and payment systems, in part requiring higher cash reserves. While on the topic of Australia: the formerly beloved commodity currency took a beating last year. While pessimism reigned in Australia, New Zealand was on a tear. In fact, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is expected to raise rates a couple of times this year. Historically, both of these currencies are highly correlated to one another. Based on fundamentals, the New Zealand dollar should do great and continue to beat the Australian dollar. However, New Zealand isn’t exactly the biggest country and its currency can be notoriously volatile. So while things look good, that provides no assurance the currency will actually do well. At some point, good economic indicators coming out of China may well push up the Australian dollar and cause substantial profit-taking in the New Zealand dollar. Norway & Sweden Throughout 2013, we became increasingly cautious about Norway. From a dovish central bank concerned about a strong currency to an increasingly populist government, we became rather disillusioned with the prospects. That, in turn, left the Swedish krona as the Nordic currency of choice. Sweden is likely to cut rates once more this year, although that action is mostly priced in. Being a smaller country, policy shifts tend to be more dynamic. Canada Oh Loonie! Once dovish Mark Carney left the Bank of Canada, we – like many in the markets – thought his hawkish deputy Tiff Macklem would succeed him. Not only did he not succeed him, he is calling it quits. Aside from losing hawkish intellectual leadership, the Bank of Canada has had, to put it mildly, fostered a benign neglect of its currency. The key risk we see with our cautious outlook for the Loonie is that we are not alone in that view. Emerging Markets Emerging markets tend to be less liquid than developed markets. Last spring showed this matters: when volatility spikes because of uncertainty over the future course at the Fed, the previously perceived free lunch in capturing yield with low volatility in emerging market local debt markets causes stomach cramps. Not only will we likely have local disturbances with numerous elections coming up in emerging markets, but we think the heavy hand of policy makers in major economies may well persist. Most vulnerable in this context are the weaker EM countries – those with current account deficits. The notably exception here is India, where Reserve Bank Governor Raghuram Rajan has introduced major reforms since taking the helm last September. While Indian reforms always suffer from implementation risk, the Indian rupee has a lot of catching up to do. Conversely, however, even as Brazil may yet again raise rates, Brazil lacks a credible inflation fighting strategy. China China is moving ever closer towards opening up its capital account. This may well be the year where China reduces its U.S. Treasury purchases in a meaningful way and paves the way for market forces to play a greater role in setting exchange rates. For those with doubts about China’s commitment, please read this interview with Yi Gang, Deputy Governor of the People’s Bank of China, as well as administrator of SAFE, China’s foreign exchange regulator. In our assessment, little can stop the rise of the Chinese yuan as a major currency in the coming years. The creation of a major currency takes more than a free float, but China is fostering all the other necessary elements. Gold The biggest risk for 2014 may be economic growth. That’s because economic growth throws a wrench into the bond market, making it ever more difficult for developed countries to finance their deficits. We believe it’s very unlikely the U.S. could afford significantly positive real interest rates for an extended period. As indicated earlier, theFed may have all but promised to be “behind the curve” in raising rates. Even if the Fed wanted to raise rates, the stockpile of excess reserves accumulated from QE means that they will have to rely on new tools that require them to pay increasing amounts of interest directly to financial institutions. The potential political backlash of these new rate-setting tools may make it more difficult to mop up liquidity. Meanwhile, if economic growth and demand for loanable funds comes back, the banking system could pyramid those excess reserves into new loans that could dramatically increase the money supply and stoke inflation. The Fed may need to rely on capital adequacy ratios to contain bank balance sheet expansion, but it should be easy for banks to raise more capital in a good economic environment. It’s in this context that the future may look bright for the shiny metal. Importantly, even with the price decline in 2013, gold played its role as a diversifier. The time to rebalance an equity portfolio is when times are good. We are not suggesting all this rebalancing should necessarily go into gold, but we are not convinced the bond market is the right place either. As our readers may well know, we think that the currency markets may provide opportunities that offer diversification. |

01-04-14 | MACRO-MONETARY | GLOBAL MACRO |

|||

| � | � | � | � | |||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

� | � | � | |||

THIS IS A STRUCTURAL PROBLEM Not A Cyclical Problem Solved By Keynesian Solution |

01-15-14 | � | � | |||

|

01-13-14 | � | � | |||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | � | � | � | |||

SHADOW BANKING - Safe Harbor Privileges The roots of shadow banking 01-16-14 Enrico Perotti The ‘shadow banking’ sector is an ill-defined financial segment that expands and contracts credit outside the regulatory perimeter.

Defining shadow banking by function By definition, shadow banking is not a precise category. In this column, I focus on financial intermediaries that take credit risk. Banks acquire illiquid risky assets, funding them with inexpensive, demandable debt.

Confidence on immediacy ensures that demandable debt is routinely rolled over, thus supporting long-term lending and high leverage.1 As bank credit volume is constrained by capital ratios and deposit base, financial markets have thought of new ways to carry risky assets on inexpensive funding. Shadow banking requires creating a variant of demandable debt, credibly backed by a direct claim on liquidity. But the dominant funding channel is issuing collateralised financial credit, such as repos or derivative-based claims.2 �This is the source of shadow banks’ very short-term, inexpensive funding source. How can these liabilities deliver investors credible liquidity upon demand? Jump the running queue: Superior bankruptcy rightsSecurity-pledging (the collateral part of collateralised financial credit) grants access to easy and cheap funding thanks to the steady expansion in the EU and US of “safe harbour status” – the so-called bankruptcy privileges for lenders secured on financial collateral. Critically, lenders in this collateralised financial credit transaction can immediately repossess and resell pledged collateral. They also escape most other bankruptcy restrictions such as cross default, netting, eve-of-bankruptcy and preference rules (see Perotti 2010).

The consequences became visible upon Lehmann’s default, when its massive stock of repo and derivative collateral was taken and resold within hours. This produced a shock wave of fire sales of ABS holdings by safe harbour lenders. While these lenders broke even,3 �their rapid sales spread losses to all others, forcing public intervention. When the safe harbour provisions were massively expanded in a coordinated legislative push in the US and EU (Perotti 2011),4 they supported an extraordinary expansion of shadow banking credit and mortgage risk taking. The guaranteed ease of escape fed the final burst in maturity and liquidity mismatch in the 2004-2007 subprime boom, where credit standards fell through the floor. Borrowing securities to generate collateralised financial creditWhile shadow banks expanded with securitisation, they can also rely on the liquidity of assets they do not own. They do this by borrowing securities from insurers, pension and mutual funds, custodians, and collateral reinvestment programmes.5 In exchange, the beneficial (i.e. real) owners of such securities receive fees for lending the assets and they book these as yield enhancement. Borrowed securities are then pledged to ‘repo lenders’ (the short name for credit grantors in a collateralised financial credit transaction) or posted as margins on derivative transactions. Experienced asset managers who lend securities in this way protect themselves via collateral swaps, i.e. a related transaction where the security borrower pledges collateral of lower liquidity. This so-called ‘liquidity risk transformation chain’ (which transforms illiquid assets into short term credit) may have more links. The financial logic behind the liquidity risk transformation chain is clear. Security pledging activates the liquidity value of assets from long-term holders who do not need it. Such extraction of unused liquidity value may be seen as enhancing “financial productivity”. It certainly increase asset liquidity, and boosts securitisation. Yet this can be an illusory gain, flattering market depth in normal times, at the cost of greater illiquidity at times of distress. The repo lenders and security lenders typically require a more than one-to-one exchange to protect themselves against the possibility of the collateral losing value. These ratios are called ‘haircuts’ since each $1 of collateral generates less than $1 of credit. Shadow banking runs: Rising haircutsA jump in market haircuts, and ultimately a refusal to roll over security loans or repos, is the classic shadow bank run.

In both cases this triggers fire sales.

First, they are not natural holders. Second, they do not suffer from a fire sale as long as the price drop is less than their haircut. Third, they are aware that others are repossessing similar collateral at the same time, so they have an incentive to front sell.

First, they may wish to re-establish their portfolio profile. More critically, they legally need to sell within days to be able to claim any shortfall in bankruptcy court.

While central banks are not in charge of shadow banks, they do come under pressure to stop fire sales and create outside liquidity. This completes the banking analogy. The safe harbour debateIt is now evident that shadow banks need the safe harbour privileges to replicate banking. No financial innovation to secure escape from distress can match the proprietary rights granted by the safe harbour status, which ensure immediate access to sellable assets. Traditional unsecured lenders have taken notice, and now request more collateral, squeezing bank funding capacity and limiting future flexibility. Many attentive observers find such an unconditional assignment of superpriority to repo and derivative claimants excessive.6 Duffie and Skeel (2012) discuss in an excellent summary the merit of safe harbour. In their words:

All these arguments demand attention. Repo lenders and derivative counterparties enjoy not just immediacy in default, but also reset margins daily. By construction, this produces a unique safe claim. Just as insured depositors, these claimants can afford to neglect credit risk, and perform no monitoring role. Collateral lending, by splitting up liquidity transformation, lengthens credit chains and expands the number of connections among intermediaries, contributing to systemic risk (Gai et al. 2011). What should happen to the safe harbour privileges?The main proposals aim at restricting eligibility. Tuckman (2010) suggested only cleared derivatives should enjoy the status. Duffie and Skeel argue it may be limited to appropriately liquid collateral (thus not ABS!) and only transparent uses (derivatives listed on proper clearing exchanges). In recent research (Perotti 2011), I suggest that claims be publicly registered (just as secured real credit is) as a precondition for safe harbour status. This will ensure proper disclosure, essential to macro prudential regulators, and avoids unauthorised or misunderstood (re)hypothecation. Investors who wish to claim superpriority in distress seek a scarce resource. They should be paying for the privilege, and for any risk externality it creates. In normal times, a low charge should be levied on registered claims. Charges should be adjusted countercyclically, lowered in difficult times, and raised when aggregate liquidity risk builds up, to brake an otherwise uncontrollable expansion. Other approaches involve limiting the stock of safe harbour claims directly (Stein 2012) by a cap and trade model, which a registry receiving fees could support. A critical issue is the treatment of collateral posted for central bank refinancing. For central banks to operate as ultimate liquidity providers, their claims should not be undermined. A specific privilege for eligible collateral is justified, as central banks are by definition not likely to create fire sales. ConclusionsThanks to the safe harbour rules, a shadow bank can hold risky illiquid assets and earn full risk premia with funding at the overnight repo rate. In what is essentially a synthetic bank, repo and collateral swap haircuts act as market-defined capital ratios. Liquidity transformation across states and entities has procyclical effects. It enhances credit and asset liquidity in normal or boom times, at the cost of accelerating fire sales in distress. While any reform to the shadow banking funding model should take into account its favourable effects on asset liquidity and credit in normal times, the associated contingent liquidity risk is not at present controllable (nor is it well measured!). There is an academic consensus that a balance has to be struck (Acharya et al. 2011; Brunnermeier et al. 2011; Gorton and Metrick 2010; Shin 2010). Appropriate tools are also necessary to align capital and risk incentives in banks and shadow banks (Haldane 2010). Security lending may also undermine Basel III liquidity (LCR) rules. At a time when all lenders seek security, questioning the logic of safe harbour provisions may seem unwise. Yet at the system level, it is simply impossible to promise security and liquidity to all. Uncertainty on the stock of pledged assets may create a self-reinforcing effect, feeding a frenzy among lenders to all seek ever-higher priority. This is already taking place, and is ultimately unsustainable at the individual and aggregate level. Finally, it is questionable whether the highest level of protection should be granted to collateralised lenders, and to shadow bank funding, over all other investors. For all these reasons, regulators and the wider society need to make an informed decision. ReferencesAcharya, Viral, Arvind Krishnamurthy, and Enrico Perotti (2011), “A consensus view on liquidity risk”, VoxEU.org, 14 September. Acharya, Viral and Sabri �nc� (2012), “A proposal for the resolution of systemically important assets and liabilities: the case of the repo market”, CEPR DP 8927, April. Brunnermeier, Markus, Gary Gorton, and Arvind Krishnamurthy (2011), “Risk Topography”, NBER Macroannual 2011. Duffie, Darrell and David Skeel (2012), A Dialogue on the Costs and Benefits of Automatic Stays for Derivatives and Repurchase Agreements, Stanford University, March. Haldane, Andrew (2010), “The $100 Billion Question”, Bank of England, March. Gai, Prasanna, Andrew Haldane, and Sujit Kapadia (2011), “Complexity, Concentration and Contagion”, Bank of England discussion paper. Gorton, Gary, and Andrew Metrick (2010), “Regulating the Shadow Banking System”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2):261-297. Perotti, Enrico (2010), “Systemic liquidity risk and bankruptcy exceptions”, VoxEU.org, 13 October. Perotti, Enrico (2011), “Targeting the Systemic Effect of Bankruptcy Exceptions”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 52 and Journal of International Banking and Financial Law (2011) Shin, Hyun Song (2010), “Macroprudential Policies Beyond Basel III”, Policy memo. Stein, Jeremy (2010), “Monetary Policy as Financial-Stability Regulation”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1):57-95. Tucker, Paul (2012), “Shadow Banking: Thoughts for a Reform Agenda”, Speech at the European Commission High Level Conference, 27 April, Brussels. Tuckman, Bruce (2010), Amending Safe Harbors to Reduce Systemic Risk in OTC Derivatives Markets, Centre for Financial Stability, New York. 1Historically, confidence was supported by high capital, reputation and limited competition. As competition increased and capital fell, central banks’ emergency liquidity transformation and deposit insurance allowed steadily higher credit and bank leverage. 2Trivially, shadow banks may also access bank credit lines (as SIVs did). 3The rest of the creditors had to wait years to get less than 20 cents on the dollar. 4Limited safe harbour status was granted as exceptions in the 1978 US Bankruptcy code, limited to Treasury repos and margins on futures exchanges for qualifying intermediaries. They were broadened progressively to include margins on OTC swaps. The massive changes took place in 2004, when any financial collateral pledged under repo or derivative contracts, whether OTC or listed, by any financial counterparty, came to enjoy the bankruptcy privileges (Perotti 2011). 5According to Poszar and Singh (2011): “At the end of 2010.. about $5.8 trillion in off-balance sheet items of banks related to the mining and re-use of source collateral… down from about $10 trillion at year end-2007”.� 6Creation of new proprietary rights is exceedingly rare. Limited liability is the last main case. |

01-16-14 | GLOBAL- GEO-POLITICAL- GROUP-INTERNATIONAL_ BANKING- SHADOW_BANKING |

CENTRAL BANKS |

|||

|

01-14-14 | � | � | |||

| � | � | � | ||||

| Market | ||||||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET | � |

� | � | |||

| � | � | � | ||||

VALUATIONS - Gap between price inflation and unit labor cost inflation Drives Profits The Most Important Driver Of Profit Margins 10-30-13 BI One of the hottest debates among experts covering the markets and the economy is over the sustainability of record high profit margins. Goldman Sachs' Jan Hatzius offered his forecast for margins in his "10 Questions for 2014" note. "Will profit margins contract?" asked Hatzius. "No." "As shown in Exhibit 10, "The most important driver of profit margins is the gap between price inflation and unit labor cost inflation. When prices grow faster than unit labor costs, firms typically manage to raise their profit margins, and vice versa. In our view, the price/ULC gap is likely to move back into slightly positive territory in 2014." Hatzius expects wage growth to stay low at least in the near-term. "[T]he underlying trend calculated from the three primary measures of hourly wages—average hourly earnings, the employment cost index, and compensation per hour—is still only growing 2%," added Hatzius. "Going forward, we expect only a modest acceleration to perhaps 2.5%. Meanwhile, we expect productivity growth to reaccelerate to 1.5%-2%. Together, these numbers imply unit labor cost growth of 0.5%-1%, which would be slightly below the rate of price inflation of 1%-1.5%." Labor market slack is one of the main reasons why economists believe inflation will stay low for a while. But getting back to profit margin dynamics, we know that wage growth is only part of the story. "Of course, the price/ULC gap is not the only driver of margins," continued Hatzius. "But other factors are also likely to look reasonably friendly. We expect foreign profits to improve in 2014 as the global economy gathers some momentum, and see no major changes in corporate income taxes or financial profits." |

01-13-14 | MACRO--FUNDAMENTALS-VALUATIONS | ||||

VALUATIONS - Historically Elevated Margins Corporate profit margins are at all-time highs. The stock market's bulls and bears are willing to agree with this fact. But that's about it. The bears are convinced that margins are doomed to mean revert. Among other things, they note that companies are no longer able to squeeze further productivity out of their workforces. They also warn that rising interest rates mean higher interest expenses. The bulls will acknowledge that margins are at risk of pulling back especially if revenues fall or if the economy goes into recession.� But for now, they don't see much giveback. Furthermore, they believe that margins are in a structural upswing as companies have slashed their exposures to debt and increased their exposures to low-cost, high margin overseas regions. Blackstone's Byron Wien thinks this is a crucial story. In fact, when Business Insider asked Wien for what he considered to be the most important chart of the year, he sent us a chart of historical profit margins on the S&P 500. "This chart worries me," said Wien. "Profit margins are at a peak and they appear to be rolling over. This could mean trouble for 2014 earnings." |

01-13-14 | MACRO--FUNDAMENTALS-VALUATIONS | ||||

VALUATIONS- JEFF SAUT: I Don't Buy The Profit Margin Compression Argument, I Think The S&P 500 Can Go To 2,000 01-04-14 BI "Year-end letters are difficult to write because there is always a tendency to discuss the year gone by or, worse, attempt to forecast the coming year," said Raymond James' Jeff Saut earlier this week. But perhaps begrudgingly, Saut offered his forecast anyway. He warms into it by first reminding us of the various psychological hurdles in recent years:

And it's not just about Fed balance sheet expansion. Saut sees plenty of bullish fundamentals driving stocks higher.

Saut thinks it's possible we go straight up without a meaningful sell-off for a while.

And since it's one of the hottest debates in the market these days, Saut offered his position on record high profit margins.

So overall, he's bullish � |

01-13-14 | MACRO--FUNDAMENTALS-VALUATIONS | ||||

| COMMODITY CORNER - HARD ASSETS | � | PORTFOLIO | � | |||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � | |||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | � | PORTFOLIO | � | |||

| � | � | � | ||||

| THESIS Themes | ||||||

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | � | � | � | |||

GLOBAL IMBALANCES - The Real Source of the Financial Crisis

A Requiem for Global Imbalances 01-13-14 Barry Eichengreen is Professor of Economics and Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley, and a former senior policy adviser at the International Monetary Fund. His most recent book is Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International

Back in 2004, there were two schools of thought on global imbalances.

We now know that both views were wrong. Global imbalances did not continue indefinitely.

There was a crisis, to be sure, but it was not a crisis of global imbalances. Although the US had plenty of financial problems, financing its external deficit was not one of them. On the contrary, the dollar was one of the few clear beneficiaries of the crisis, as foreign investors, desperate for liquidity, piled into US Treasury bonds. The principal culprits in the crisis were, rather, lax supervision and regulation of US financial institutions and markets, which allowed unsound practices and financial excesses to build up. China did not cause the financial crisis; America did (with help from other advanced economies). This is not to deny the enabling role of international capital flows. But the flows that mattered were not the net flows of capital from the rest of the world that financed America’s current-account deficit. Rather, they were the gross flows of finance from the US to Europe that allowed European banks to leverage their balance sheets, and the large, matching flows of money from European banks into toxic US subprime-linked securities. Both critics and defenders of global imbalances almost entirely overlooked these gross flows in both directions across the North Atlantic. The next time that global imbalances develop, analysts will – we must hope – know to look beneath their surface. But will there be a next time? A couple of years ago, forecasters were confident that global imbalances would reemerge once the crisis passed. That now seems unlikely: Neither the US nor China is going back to its pre-crisis growth rate or spending pattern. Nor are earlier trade balances about to reemerge. America’s trade position will be strengthened by the shale-gas revolution, which promises energy self-sufficiency, and by increases in productivity that auger further re-shoring of manufacturing production. Emerging markets, for their part, have learned that export surpluses are no guarantee of rapid growth. Nor do large international reserves guarantee financial stability. There are better ways to enhance stability, from strengthening prudential supervision to taxing and controlling destabilizing capital flows and letting the exchange rate adjust. All of this suggests that the accumulation of foreign reserves by emerging and developing countries – another phenomenon over which much ink has been spilled – may be about to peak. Then it will be just another problem laid to rest. |

01-15-14 | MACRO OUTLOOK THESIS GLOBALIZATION TRAP |

||||

2013 - STATISM |

� | � | � | |||

2012 - FINANCIAL REPRESSION |

� | � | � | |||

2011 - BEGGAR-THY-NEIGHBOR -- CURRENCY WARS |

� | � | � | |||

2010 - EXTEND & PRETEND |

� | � | � | |||

| THEMES | ||||||

| NATURE OF WORK -PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX | � | � | � | |||

| GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY & INSTABILITY | � | � | � | |||

| CENTRAL PLANINNG -SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER | � | � | � | |||

| SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX -STATISM | � | � | � | |||

| STANDARD OF LIVING -GLOBAL RE-ALIGNMENT | � | � | � | |||

| CORPORATOCRACY -CRONY CAPITALSIM | � | � | � | |||

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE -MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES.. |

� | � | � | |||

| SOCIAL UNREST -INEQUALITY & BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | � | � | � | |||

| CATALYSTS -FEAR & GREED | � | � | � | |||

| ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | � | � | � | |||

| GENERAL INTEREST | � |

� | � | |||

| TO TOP | ||||||

|

||||||

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

���

���

TO TOP

�

�

�

�

�� TO TOP

�

�

�

The flows that mattered (Regarding the Financial Crisis) were not the net flows of capital from the rest of the world that financed America’s current-account deficit. Rather, they were the gross flows of finance from the US to Europe that allowed European banks to leverage their balance sheets, and the large, matching flows of money from European banks into toxic US subprime-linked securities. Both critics and defenders of global imbalances almost entirely overlooked these gross flows in both directions across the North Atlantic.

The flows that mattered (Regarding the Financial Crisis) were not the net flows of capital from the rest of the world that financed America’s current-account deficit. Rather, they were the gross flows of finance from the US to Europe that allowed European banks to leverage their balance sheets, and the large, matching flows of money from European banks into toxic US subprime-linked securities. Both critics and defenders of global imbalances almost entirely overlooked these gross flows in both directions across the North Atlantic.