|

Scroll TWEETS for LATEST Analysis

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

|

|

Theme Groupings |

|

Investing in Macro Tipping Points

THESE ARE NOT RECOMMENDATIONS - THEY ARE MACRO COMMENTARY ONLY - Investments of any kind involve risk. Please read our complete risk disclaimer and terms of use below by clicking HERE |

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for:

LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

"BEST OF THE WEEK "

|

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags |

TIPPING POINT

or

THEME / THESIS

or

INVESTMENT INSIGHT

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

|

|

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE - Money & Politics

Excerpted from: The Value Of Wealth 01-12-15 Raul Ilargi Meijer via The Automatic Earth blog,

Please see this against the backdrop of US presidential candidates raising hundreds of millions of dollars even just for their preliminary campaigns.

Back in October, HuffPo had this portrait of Uruguayan President José Mujica.

Mujica says that money should be kept out of a political system, because if it isn’t it will end up buying and eating that system whole. (Too late for the US and Europe, but perhaps not for Uruguay).

‘World’s Poorest President’ Explains Why We Should Kick Rich People Out Of Politics

People who like money too much ought to be kicked out of politics, Uruguayan President José Mujica told CNN en Español [..] “We invented this thing called representative democracy, where we say the majority is who decides,” Mujica said in the interview. “So it seems to me that we [heads of state] should live like the majority and not like the minority.” Dubbed the “World’s Poorest President” in a widely circulated BBC piece from 2012, Mujica reportedly donates 90% of his salary to charity.

Mujica’s example offers a strong contrast to the United States, where in politics the median member of Congress is worth more than $1 million and corporations have many of the same rights as individuals when it comes to donating to political campaigns. “The red carpet, people who play – those things,” Mujica said, mimicking a person playing a cornet. “All those things are feudal leftovers. And the staff that surrounds the president are like the old court.”

“I’m not against people who have money, who like money, who go crazy for money,” Mujica said. “But in politics we have to separate them. We have to run people who love money too much out of politics, they’re a danger in politics… People who love money should dedicate themselves to industry, to commerce, to multiply wealth. But politics is the struggle for the happiness of all.”

Asked why rich people make bad representatives of poor people, Mujica said: “They tend to view the world through their perspective, which is the perspective of money. Even when operating with good intentions, the perspective they have of the world, of life, of their decisions, is informed by wealth. If we live in a world where the majority is supposed to govern, we have to try to root our perspective in that of the majority, not the minority.”

“I’m an enemy of consumerism. Because of this hyperconsumerism, we’re forgetting about fundamental things and wasting human strength on frivolities that have little to do with human happiness.”

He lives on a small farm on the outskirts of the capital of Montevideo with his wife, Uruguayan Sen. Lucia Topolansky and their three-legged dog Manuela. He says he rejects materialism because it would rob him of the time he uses to enjoy his passions, like tending to his flower farm and working outside. “I don’t have the hands of a president,” Mujica told CNN. “They’re kind of mangled.”

Money and politics don’t mix, or at least not in a democracy. And I don’t see any exceptions to that rule. Mujica is right: if and when the majority of people in a country are poor, which is true just about everywhere, and certainly in the Anglo world and most EU countries, then their president should be poor too.

Ask anyone if they would like to have $1000, or $10,000 or $1 million or more, and you know that the answer would be. But Michael Lewis shows that none of it would make you any happier, if you already have – or make – enough to survive on. Still, it’s generally accepted that more is always good.

Michael Lewis writes in ‘Extreme Wealth Is Bad for Everyone – Especially the Wealthy’:

What is clear about rich people and their money — and becoming ever clearer — is how it changes them. A body of quirky but persuasive research has sought to understand the effects of wealth and privilege on human behavior — and any future book about the nature of billionaires would do well to consult it.

One especially fertile source is the University of California at Berkeley psychology department lab overseen by a professor named Dacher Keltner. In one study, Keltner and his colleague Paul Piff installed note takers and cameras at city street intersections with four-way Stop signs. The people driving expensive cars were four times more likely to cut in front of other drivers than drivers of cheap cars.

The researchers then followed the drivers to the city’s crosswalks and positioned themselves as pedestrians, waiting to cross the street. The drivers in the cheap cars all respected the pedestrians’ right of way. The drivers in the expensive cars ignored the pedestrians 46.2% of the time – a finding that was replicated in spirit by another team of researchers in Manhattan, who found drivers of expensive cars were far more likely to double-park.

In yet another study, the Berkeley researchers invited a cross section of the population into their lab and marched them through a series of tasks. Upon leaving the laboratory testing room, the subjects passed a big jar of candy. The richer the person, the more likely he was to reach in and take candy from the jar — and ignore the big sign on the jar that said the candy was for the children who passed through the department.

Maybe my favorite study done by the Berkeley team rigged a game with cash prizes in favor of one of the players, and then showed how that person, as he grows richer, becomes more likely to cheat. In his forthcoming book on power, Keltner contemplates his findings:

If I have $100,000 in my bank account, winning $50 alters my personal wealth in trivial fashion. It just isn’t that big of a deal. If I have $84 in my bank account, winning $50 not only changes my personal wealth significantly, it matters in terms of the quality of my life — the extra $50 changes what bill I might be able to pay, what I might put in my refrigerator at the end of the month, the kind of date I would go out on, or whether or not I could buy a beer for a friend. The value of winning $50 is greater for the poor, and, by implication, the incentive for lying in our study greater. Yet it was our wealthy participants who were far more likely to lie for the chance of winning fifty bucks.

There is plenty more like this to be found, if you look for it. A team of researchers at the New York State Psychiatric Institute surveyed 43,000 Americans and found that, by some wide margin, the rich were more likely to shoplift than the poor. Another study, by a coalition of nonprofits called the Independent Sector, revealed that people with incomes below 25 grand give away, on average, 4.2% of their income, while those earning more than 150 grand a year give away only 2.7%. A UCLA neuroscientist named Keely Muscatell has published an interesting paper showing that wealth quiets the nerves in the brain associated with empathy.

If you show rich people and poor people pictures of kids with cancer, the poor people’s brains exhibit a great deal more activity than the rich people’s. “As you move up the class ladder,” says Keltner, “you are more likely to violate the rules of the road, to lie, to cheat, to take candy from kids, to shoplift, and to be tightfisted in giving to others. Straightforward economic analyses have trouble making sense of this pattern of results.”

|

01-13-15 |

FIDUCIARY FAILURE |

9 - Global Governance Failure |

CHECK OUT OUR PAGE DEDICATED TO FINANCIAL REPRESSION

The Financial Repression AuthorityTM

|

| THESIS & THEMES |

|

|

|

FINANCIAL REPRESSION - In the News

"We Are The Subjects of a Grotesque Monetary Experiment"

FRA Guest Tim Price writes:

"As investors we are all now the subjects of a grotesque monetary experiment. This experiment has never been tried before, and its outcome remains uncertain. The unproven thesis, however, runs something like this: six years into a second Great Depression, the only 'solution' is for central banks to print ever greater amounts of money. Somehow, gifting free money to the banks that helped precipitate the crisis will lead to a ‘trickle down’ wealth effect. Instead of impoverishing those with savings, inflation will be some kind of miraculous curative, and it must be encouraged at all costs. It bears repeating: we are in an extraordinary financial environment.

In the words of the fund managers at Incrementum AG:

"We are currently on a journey to the outer reaches of the monetary universe."

The market – a quaint concept of a bygone age – has largely disappeared. It has been replaced throughout the West by bureaucratic manipulation of prices, in part known as QE but better described as financial repression."

A Global Wall Street Party?

The Daily Bell sees the mainstream meme of an economic recovery with rising interest rates, but thinks otherwise .. emphasizes the result of low interest rates globally has been "malinvestments" & the financial errors of the past have not been liquidated - this is bad for efficiency, productivity & sustainability

"The Federal Reserve has used

- Regulation,

- Insider buying and

- Monetary policy

... to boost what we call the Wall Street Party.

If we're correct, there are intentions to spread this party around the world, creating a kind of equity mania that may last far longer than one or two years.

One of the easiest ways to fuel a stock explosion is to print money. All great run-ups, from what we can tell, have involved the overprinting of currency and subsequent distortive asset expansion.

Given this determination to ensure a flow of easy money, you might not want to discount the Wall Street Party too soon. It may, as we've suggested before, be going global.'

New Findings Point to “Perfect Storm” Brewing

INET Economics posted essay on new research shedding light on how today’s advanced economies depend on private sector credit more than anything we have ever seen before .. the research work indicates that our economic future could be very different from our recent past, when financial crises were relatively rare

"Crises could become more commonplace, which will impact every stage of our financial lives, from cradle to retirement. Do we just fasten our seatbelts for a bumpy ride, or is there a way to smoothe the path ahead?"

more financial instability will introduce more uncertainty down the line

"Operating in this milieu, the central banks, the governments, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and other parts of the macro-financial policy world are now taking a much keener interest in what the pros and cons of different financial regulatory structures and various macroprudential tools (designed to identify and lessen the risks to the financial system) might be."

Macroprudential tools entail Financial Repression

- Inflation,

- Negative interest rates,

- Ring fencing regulations &

- Obfuscation.

India Squeezed by Financial Repression

KUNAL KUMAR KUNDU Writes from NEW DELHI - The least desirable outcome of the recently presented union budget of India was a complete undermining of the sanctity of the budget numbers. The cash strapped government had and continues to adopt various dubious means of keeping its official fiscal deficit number under check while continuing to spend its scarce resources on leaky social sector programs. (See Chidambaram shows dangerous budget skillsAsia Times Online, March 4, 2013). Funding expenditures of such magnitude in the face of revenue scarcity leads to what is called Financial Repression.

The term financial repression was introduced in 1973 by Stanford economists Edward S Shaw and Ronald I McKinnon. It was meant to include such measures as

- Directed lending to the government,

- Caps on interest rates,

- Regulation of capital movement between countries and

- A tighter association between government and banks.

In layman's term, it refers to the means by which the government expropriates savings of ordinary people or corporations. Clearly financial repression is a key ally of profligate governments.

In its crudest form, financial repression was visible in the recent budget exercise by Finance Minister P Chidambaram, which was resorted to to enable the government to show a lower fiscal deficit and, thereby impress the credit rating agencies.

The state-owned oil companies were forced to bear 40% of the total calculated oil subsidies, and even the remaining amount that is to be paid by the government is done so with an inordinate delay which will force the oil companies to go on a borrowing spree for sheer survival. This flexing of muscles by the government not only reduces its borrowing requirement but also provides some relief in its debt servicing requirement.

All of this, for a policy that:

- Destroyed private competition (since subsidies are available only to the state-owned companies and hence private sector retailing of petrol, diesel and even cooking gas did not take off as the private companies were not in a position to sale their products at less than the cost price, which the state-owned companies did;

- Is enjoyed mostly by the rich, as reported in an International Monetary Fund study. Even the government's recently released annual economic survey believes that more than half of rural rich corner almost the entire cooking gas subsidy, leaving practically nothing for the poor for whom it is earmarked.

Given the government's mindless spending on such schemes, many with questionable benefits, the government's borrowing requirements remain elevated. However, not much of the borrowing is done from lenders who are willing to lend. In fact, a good chunk of government bond issuance is forcibly placed with various financial entities. These include banks, insurance companies and pension funds.

Banks, for example, are forced to set aside 23% of their deposits in government bonds as statutory liquidity ratio as part of what is called prudential management. That apart, they have to maintain 4% (it was higher earlier) of their deposits as cash reserve ratio, on which the government has stopped paying any interest whatsoever since March 31, 2007. In all, the banking sector has to keep 27% of their deposits with the government.

The pension system operated by the Employee Provident Fund Organization (EPFO) is almost entirely invested in domestic government bonds. That apart, of the 12.11 trillion rupees (US$222 billion) invested by life insurance companies on March 31, 2012, 38.64% was invested in central government securities; a further 17.71% was invested in state government and other approved securities.

The Indian financial policy, therefore, ensures that the government gets roughly all EPFO assets, more than half of the assets of life insurance companies and more than a quarter of the assets of banks.

Not that financial repression is new in India. In fact, this is true for all developing economies. For a capital-scarce country like India, capital control was a natural outcome, since the idea was to direct savings toward investment in certain targeted sectors as part of a development plan.

Financial repression took the form of government's ownership of intermediaries, restrictions on interest rates, control of foreign exchange (especially outflow), credit schemes that are favorable to a few sectors and so forth. Regulation also stipulated (and this continues to be the case) that the banks hold a large share of their assets in public debt instruments. These debt instruments paid below-market rate interest and hence imposed an implicit tax on financial intermediation while providing cheap source of capital to the government.

Unfortunately, for India, the requirement to follow such policies has transcended the need to address various development objectives; it is now being resorted to simply because governments of various hues have failed to adhere to fiscal discipline. I believe that the fiscal deficit is but a natural consequence for a capital scarce developing economy like India that strives to move to a path of high and sustainable growth. The problem lies with the quality of the deficit, as wasteful expenditures and politically motivated populist measures contaminate the nature of the deficit, thereby leaving very little fiscal space to carry out the developmental activities.

Thus disinvestment efforts by the government are being bailed out by state-owned institutions like the State Bank of India and the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LICI). The government has arm-twisted the Insurance Regulatory Development Authority to allow LICI to exceed the cap of 10% that an insurance company can own in any listed company.

Even the cash rich state-owned companies are being made to use their funds to buy stakes in other companies whose shares the government plans to sell, irrespective of whether such acquisitions make sense for the acquiring companies. Without such support, the government's disinvestment program during the fiscal year 2012-13 would have been an utter failure.

What is even more galling is that, while the government's wasteful expenditure is on the rise, it is way behind other countries (even many poorer countries) in terms of the share of gross domestic product spent on health and education - higher spending on which is essential if India is to reap the demographic dividend of its young population.

So the government has, very recently, mandated that corporate entities with a net profit of 50 million rupees and turnover of 10 billion rupees should mandatorily spend 2% of their net profit on acts of "Corporate Social Responsibility" - a perfect example of how a government forces private sector entities to fill in the void created by their inability.

To conclude, financial repression engendered by systemic inefficiency has the potential to distort savings and investment activity in the economy and eventually impact growth. It's time India learned from the Chinese experience and finally showed the courage to take appropriate policy measures to right the wrong. However, given the way the political circus playing out in the country, that is a long shot.

|

01-13-05 |

THEMES |

FINANCIAL REPRESSION

|

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - Jan 11th, 2014 - Jan 17th, 2014 |

|

|

|

| RISK REVERSAL |

|

|

1 |

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION |

|

|

2 |

| BOND BUBBLE |

|

|

3 |

EU BANKING CRISIS |

|

|

4 |

| SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS [Euope Crisis Tracker] |

|

|

5 |

CHINA BUBBLE |

|

|

6 |

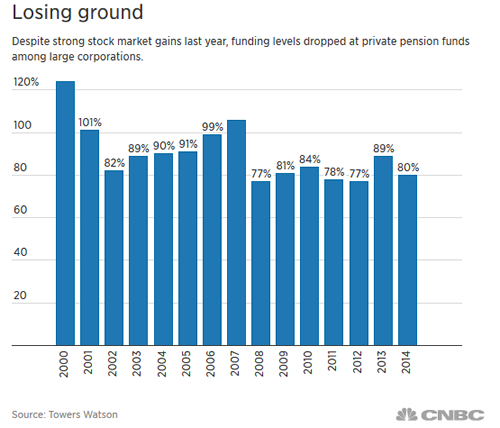

PENSIONS - Private Pensions Crisis

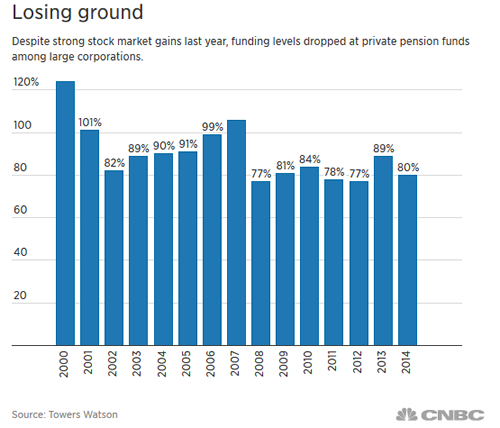

For many investors, last year's stock market gains helped make up for the heavy losses inflicted by the 2008 financial collapse. But it turned out to be a lousy year for private pension funds, which lost ground on their funding levels.

After gradual progress rebuilding the funds they need to pay retirees, the average private pension fund held about 80 percent of what it needs to cover those payments, according to a report by benefits consultant Towers Watson. That's down from 89 percent at the end of 2013 and represents an overall deficit among large corporate plans of about $343 billion, nearly double the shortfall a year earlier.

Much of the shortfall came from an increase in liabilities (or the amount they now expect to owe beneficiaries). Even as companies have pared back their defined-benefit plans—the ones that pay a guaranteed check for life—the cost of keeping that promise has increased. There are two big reasons: lower interest rates and longer life expectancies.

Low interest rates reduce the amount of money a pension fund can earn from money already set aside, raising the level it needs to generate enough cash. Interest rates also affect the way pension accountants estimate the future cost of writing all those retirement checks. Accountants look at something called the "time value of money" to compare how a given amount of money today will be worth decades in the future.

The other hit to pension funding levels came from the latest data showing that retirees are living longer than the long-term assumptions that were used to calculate how much their defined benefits will cost. Last fall, new mortality tables from the Society of Actuaries showed that between 2000 and 2014, longevity for the average male age 65 rose by two years to 86.6. For women age 65, overall longevity during the same period rose 2.4 years to age 88.8.

The SOA estimated that those gains in lifespan could add as much as 4 percent to 8 percent to a private pension plan's liability.

In a separate move last month, lawmakers finalized a last-minute, behind-the-scenes deal to shore up the government's pension insurance fund by raising premiums and allowing some troubled pension plans covering more than one employer to cut retiree benefits.

The provisions, which drew loud opposition from unions and other groups representing retirees, were part of a massive $1.1 trillion spending bill signed by President Barack Obama last month.

Proponents argued that the changes would keep the failing pension plans afloat and keep benefits flowing to retirees. But some union officials and retiree advocates, such as AARP, slammed the benefit cuts as a sneak attack on a decades-old promise to workers and their families.

Read More Congress eyes move to cut pension benefits

The fix proposed by Congress would allow some underfunded multiemployer plans to cut the benefits they pay to some current and future retirees to help cover higher premiums to shore up the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., the government insurance fund backing these plans. (Benefits reportedly would not be cut for disabled pensioners or those 80 years and older.)

About a quarter of the roughly 40 million workers who participate in a traditional defined-benefit plan are covered by multiemployer plans, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Multiemployer plans are jointly backed by employers in industries such as construction, trucking, mining and food retailing. Although many of the approximately 1,400 such plans are in good shape, an estimated 1.5 million workers are in plans that are failing.

Both public and private pension funds were hit hard by the 2008 financial crisis, which wiped out trillions of investments used to pay retiree benefits. Since then, many private plans have recovered those losses and are on a more solid footing.

But multiemployer plans, which typically cover smaller companies and unions, face a different set of financial challenges. Declining union enrollments, for example, mean there are fewer active workers to cover the cost benefits for retirees, many of whom are living longer than expected when these plans were established.

Multiemployer plans also face the added burden of their pooled pension liabilities. When one member of the plan fails to keep up with contributions, the burden on the other members increases.

|

01-12-15 |

US

PENSION CRISIS |

18- State & Local Government |

PENSIONS - State & Local Government Crisis

A $4.7 TRILLION STATE & LOCAL GOVERNMENT PROBLEM

REPORT: “Promises Made, Promises Broken 2014”

| |

Assets |

Liabilities |

Underfunded |

Funding % |

| 2013 |

$2.68T |

$7.42T |

$4.7* |

36% |

| 2012 |

|

|

$4.1 |

39% |

| * Official |

|

|

$1.0 |

|

Market Valuation instead of "Discount Rates" based on Historical Investment Return Assumptions

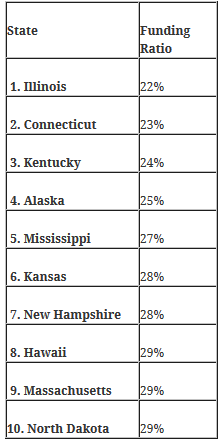

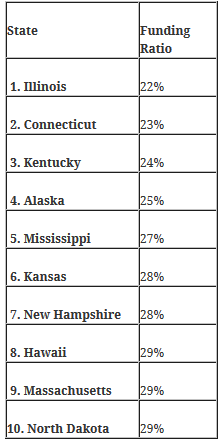

WORST BASED ON "FUNDING RATIO"

WORST BASED ON "SIZE OF BAILOUT LIABILITIES"

WORST BASED ON "PER-CAPITA LIABILITIES"

State pension funds' combined underfunding rises to $4.7 trillion 11-12-14 Pensions & Investments

State employee retirement systems are underfunded by a total of $4.7 trillion for a funding ratio of 36%, said a report from State Budget Solutions, a non-profit organization advocating state budget reform.

The report, “Promises Made, Promises Broken 2014” uses data from fiscal year 2013 comprehensive annual financial reports and actuarial valuations from individual plans. In its 2013 report, the group estimated underfunding at $4.1 trillion, or a 39% funding ratio.

The report measured state public pension liabilities by market valuation instead of discount rates based on investment return assumptions because “the discount rates that plans use are just far too high,” said Joe Luppino-Esposito, State Budget Solutions general counsel and the report's author, in an interview. A risk-free rate based on a 15-year Treasury bond rate works better when states fail to make annual contributions and address unfunded liabilities, Mr. Luppino-Esposito said. “Even if you are on target, it doesn't work. The bottom line is that on paper nothing beats a government pension. But in reality, the money isn't there,” Mr. Luppino-Esposito said.

The overall actuarial assets of state pension funds in the 50 states, according to the report, total $2.68 trillion, while liabilities total $7.42 trillion.

Using the states' own assumptions, unfunded liabilities are just over $1 trillion, the report said.

The state with the lowest funding ratio is Illinois at 22%, the report said. The state's public employee pension funds have $95 billion in assets and $426.6 billion in liabilities, according to the report.

Enormous tax hikes for next 30 years needed to honor retirement promises to state and local employees - $5 Trillion Price Tag for Public Pensions 11-08-12

2010 CONTRIBUTIONS = 5.7% OF STATE BUDGETS

FUNDING REQUIREMENT = 14.1% or $1400/Household

As strapped state and local governments scramble for ways to balance their budgets, it's become very clear that it will be impossible for many to honor their pension promises to new employees and even current retirees. According to a 2010 DATA BASED study, the cost to fully fund these promises would cost taxpayers $5 trillion over a 30-year period, or nearly $1,400 a year in higher state and local taxes and fees for every household in the country.

Contributions to pay for public employees' retirement benefits now total 5.7 percent a year of all state and local taxes, fees, and other government charges. "Government contributions to state and local pension systems must rise to 14.1 percent" to produce fully funded pension systems, the study said, and it will take 30 years to get there.

Pensions 'Timebomb' - 85% of Pension Funds Will Go Bust 04-15-14 Goldcore

EARNING 4% OR LESS

ACTUARIAL ASSUMPTIONS OF 7-8%

The “pensions timebomb” keeps on ticking and as societies we become less prepared by the day. Yet another report shows that the public pension system is in dire straits. This one comes from renowned investment manager Bridgewater Associates.

Bridgewater Associates' Study

The study estimates that public pension funds will earn an annual return of 4% or less in the coming years due to near zero percent interest rates and financial repression. That, in turn, would cause bankruptcy for 85% of the pension funds within 30 years, the study warns.

Public pension plans now have only $3 trillion in assets to invest so that they can pay out $10 trillion of retirement benefits in coming decades, according to Bridgewater. The funds would need an annual investment return of about 9% to meet those obligations, the report says.

Many pension plans assume they will earn 7% to 8% annual returns, an assumption which is far too high. But even in the best case scenario of the pension plans achieving those returns, they will face a 20% shortfall, Bridgewater notes.

Bridewater looked at a range of different market conditions, and in 80% of the scenarios, the pension funds become insolvent within 50 years.

Rockefeller Institute of Government

A little notice report issued earlier this year by the Rockefeller Institute of Government says state and local government pension systems have very significant problems.

"Bad incentives and inadequate rules allowed public sector pension underfunding to develop," the study says. "They mask the true costs of pension benefits and encourage underfunding,under-contributing, and excessive risk- taking, trapping pension administrators and government funders in potentially destructive myths and misunderstanding."

It is likely that many pension funds will go bust in the medium term and this may be a crisis that looms large sooner than the Bridgewater research suggests.

Pension funds traditional mix of equities and bonds may under perform in the coming years. Many stock markets appear overvalued after liquidity driven surges in recent years. Bonds offer all time record low yields and are at all time record highs in price. They will fall in value in the coming years.

Public Pensions Are Still Marching To Their Death 09-11-14 Forbes

Public employee pension systems have long been a source of problems. State government politicians are continually tempted to underfund pension plans in favor of using that money for something with an immediate payoff. Those same politicians also tend to grant increased pension benefits to state employees because it is a simple vote-buying scheme with no immediate budgetary cost. However, a sign of how bad the morass of public pension funds has become is that most of them have become more underfunded in the past five years. If public pensions get more underfunded in years with positive stock market gains, what hope is there for their survival?

Morningstar considers a pension plan to be so underfunded as to be declared “not fiscally sound” if it is less than 70 percent fully funded.

According to Bloomberg, in 2012 there were 26 states whose pension plans met that standard. That is bad, but when you check the pattern over time, the trend is worse.

Of those 26 states in the most trouble, only one improved its funding status from 2009 to 2012. Yet those years were after the stock market drop of the recession and during a robust stock recovery. For the years from 2009 through 2012, the S&P500 index had a cumulative return of 71.1 percent. Obviously, public pension plans are not invested only in stocks and their returns were surely lower across their full portfolios. Still, one would have expected pension plans to be in bad shape in 2008-2009 at the market bottom, but to be in improved financial health by 2012 after the market bounced back.

If public pension plans are losing ground on their funding status in years when the market is delivering above normal returns, is there any hope for their survival?

The answer is probably not, but if there is a way to save public pension funds, it will require a new political calculus by the two parties most responsible for the current sorry state of affairs: state politicians and government employee unions.

FIDUCIARY FAILURE

In the current state of political compromise between (mostly Democrat) politicians and unions, politicians vote in favor of generous pension benefits for public employee union members and then union representatives accept under-funding of those pensions. This makes the generous pension benefits seem affordable by hiding the full cost of those giveaways.

- Politicians win because they avoid the spending cuts to popular programs or the tax increases necessary to actually pay for the benefits they voted for;

- Union leaders win because they can tell their members about the new pension benefits they secured.

Unfortunately, since nothing in life is free, a cost most be paid for these decisions. That cost is the higher probability the public pension fund will collapse under the weight of this under-funding and those public sector union members will lose their pensions.

The deals hinge on a key assumption in the calculation of the cost of any deferred benefit: the expected future return on the invested funds between now and when the benefits are collected. This future expected return on the pension fund investments controls how much money the politicians need to pay into the workers’ pension funds now. A higher assumed rate of return means less money is needed now thanks to all the money the investments are assumed to make in the future.

Right now politicians and union leaders are taking a huge gamble by using expected future rates of return that are much more optimistic than reasonable. The hope is that either investment returns will save the politicians from their irresponsibility and the workers from poverty or that the courts will force states to pay up enough later to keep their promises. Union leaders are accepting such a risk because they see the only alternative to be accepting smaller pensions.

NEW YORK CITY EXAMPLE

New York City’s pension funds are a prime example.

In 2000, the City’s pension funds were more than fully funded, sitting at 136 percent of what was needed and annual contributions were around $650 million per year, or 2 percent of the city budget. Today, New York City is paying $8 billion per year (11 percent of the budget), yet the funds now hold only around 60 percent of what is needed to be fully funded.

How could this happen?

- Poor investment returns,

- Optimistic expected investment returns,

- Longer lives in retirement, and

- Promises of more generous pensions for city workers.

If Mayor de Blasio agrees to more pension benefits for workers in his current union contract negotiations, the problem is only going to get worse.

So far, union leaders have agreed to this risky strategy of overpromising and underfunding, feeling safe in the strength of many state laws protecting public employee pensions from future cuts. However, Detroit’s bankruptcy case has shown a definite flaw in this strategy. If Detroit’s final plan involves pension benefit cuts, every public employee union will need to reassess their negotiating strategy.

Having politicians and union leaders conspire to reward public employees with generous pensions and then push the costs off onto future generations was never a particularly noble endeavor. It began and still continues today because both sides win from the deal, one in votes and the other in prestige and union dues. However, Detroit may finally show the hidden dangers in such a game.

If Detroit makes other cities and states face reality and adjust their pension plans to economic reality rather than political agendas, at least Detroit’s poor employees and retired workers will have done something positive for millions of other public sector employees out there. In the meantime, public sector employees and their union leaders need to make a hard choice: settle for realistic, smaller pensions that they are sure to collect or gamble on larger pensions that can only be paid for with well-above average future investment returns or by huge tax increases. Bigger pensions only look attractive until you factor in the risk of collecting nothing.

MORE FIDUCIARY FAILURE

Congress Quietly Passed A Bill That Seriously Messes With Corporate Pensions 08-13-14 Business Insider

The WSJ article details that:

Congress passed, and Obama signed, a transportation bill that happens to contain a provision to allow companies temporary relief from fully funding their pension obligations. In the fine print of the article we learn that the pension-funding obligation comes from calculations of current interest rates, which are extraordinarily low. What companies wanted, and our leaders delivered, was a pension-funding formula that took into account interest rates of the last 25 years, rather than the last 2 years. This is a key difference.

Here’s how I assume it works: If you observe that prevailing interest rates of, say, 10 year bonds are at 2%, then you have to make the assumption that all money invested in bonds for the next ten years will return just 2% per year. That’s reasonable. And from there you can calculate how much money you’ll have in 10 years, using compound interest. (see how I always work in a link to that idea?)

The problem is that if you assume only a 2% return on your money, then you need to invest a lot more money today in order to actually have enough to meet the future obligations of your pension plan.

If you could instead assume a bond rate of return of 6% – because that was the average interest rate over the past 25 years – then you need a lot less money to fund your pension plan. Problem magically solved. Companies are happy. CEOs are happy. Workers who depend on pensions eventually are unhappy. But hey! As Meatloaf says, 2 out 3 ain’t bad.

As I’ve written previously, the low returns of bonds are a major drawback of a low interest rate environment, when you have to have enough money for the long run. Endowments and charities and pensions that previously depended on a healthy bond portfolio to kick out 5-6% returns every year are stuck either generating less money for the long run, or they’re going far out onto the risky end of the investment spectrum (over-allocating to stocks or more exotic risks) to make the numbers work.

Or, as we saw yesterday, just pretend you can get the returns on bonds that we got over the past 25 years. Ignore our actual historically low interest rates now with magical-thinking assumptions.

By the way, what happens when companies underfund their pensions?

If a company disappears or goes bust, the federal government (and therefore you and me, via taxes) picks up the unfunded pension liability through an agency known as the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation. Just as the FDIC guarantees bank deposits (up to a certain size) and insurance regulators guarantee insurance payouts (when an insurance company fails), so does the PBGC pick up pension obligations when a private company with a pension goes bust. In 2010 for example, 147 companies with pension failed, and the PBGC paid our $5.6 Billion in liabilities to pensioners.

A big factor in the GM and Chrysler bankruptcy and bailouts of 2008, for example, had to do with the government pension guaranties.

For some time before 2008, GM and Chrysler had morphed from car manufacturers with large pension plans into giant pension-liability companies that also happened to make some cars (that not enough people actually buy anymore.)

I can’t claim to know the details of the agreement signed into law yesterday, but using tricks like a 25 year average on historic interest rates, rather than current interest rates, should keep us up all night, rather frightened.

This article originally appeared at Bankers Anonymous. Copyright 2015

|

01-08-15 |

US

PENSION CRISIS |

18- State & Local Government |

| TO TOP |

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week |

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|

|

|

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|

|

|

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Market |

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

|

|

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX |

|

PORTFOLIO |

|

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX |

|

PORTFOLIO |

|

|

|

|

|

| THESIS |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP |

2014 |

|

|

2013 - STATISM |

2013-1H

2013-2H |

|

|

2012 - FINANCIAL REPRESSION |

2012

2013

2014 |

|

|

2011 - BEGGAR-THY-NEIGHBOR -- CURRENCY WARS |

2011

2012

2013

2014 |

|

|

2010 - EXTEND & PRETEND |

|

|

|

| THEMES |

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS |

|

THEME |

|

| SHADOW BANKING -LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE |

|

THEME |

|

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE |

|

THEME |

|

| ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM |

|

THEME |

|

| PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX -NATURE OF WORK |

|

THEME |

|

| STANDARD OF LIVING -EMPLOYMENT CRISIS |

|

THEME |

|

| CORPORATOCRACY -CRONY CAPITALSIM |

|

THEME |

|

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE -MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

|

THEME |

|

| SOCIAL UNREST -INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT |

|

THEME |

|

| SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX -STATISM |

|

THEME |

|

| GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY |

|

THEME |

|

| CENTRAL PLANINNG -SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER |

|

THEME |

|

| CATALYSTS -FEAR & GREED |

|

THEME |

|

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

|

|

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS |

RETAIL - CRE

|

|

SII |

|

US DOLLAR

|

|

SII |

|

YEN WEAKNESS

|

|

SII |

|

OIL WEAKNESS

|

|

SII |

|

| TO TOP |

| |

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

|

YOUR SOURCE FOR THE LATEST

GLOBAL MACRO ANALYTIC

THINKING & RESEARCH

|

�

|

2014 THESIS: GLOBALIZATION TRAP

2014 THESIS: GLOBALIZATION TRAP