|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

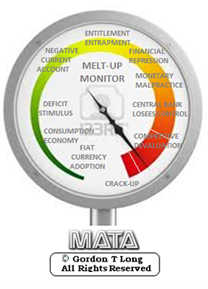

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

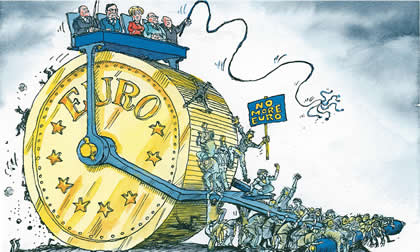

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Weekend Feb. 14th , 2015

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS

2015 THESIS: FIDUCIARY FAILURE

2015 THESIS: FIDUCIARY FAILURE

NOW AVAILABLE FREE to Trial Subscribers

174 Pages

What Are Tipping Poinits?

Understanding Abstraction & Synthesis

Global-Macro in Images: Understanding the Conclusions

![]()

| FEBRUARY | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1 - Risk Reversal |

| 2 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 3- Bond Bubble |

| 4- EU Banking Crisis |

| 5- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 6 - China Hard Landing |

| 7 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 8 - Geo-Political Event |

| 9 - Global Governance Failure |

| 10 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 11 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 12 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 15 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 16 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 17 - Credit Contraction II |

| 18- State & Local Government |

| 19 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 20 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 21 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 22 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 23 - US Reserve Currency |

| 24 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 25 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 26 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 27 - Food Price Pressures |

| 28 - Global Output Gap |

| 29 - Corruption |

| 30 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 31 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 32- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - US Reserve Currency |

| 35- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 36 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 37 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 38 - Terrorist Event |

| 39 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

| 41 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

![]() Scroll TWEETS for LATEST Analysis

Scroll TWEETS for LATEST Analysis ![]()

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

|||

"BEST OF THE WEEK " |

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags | TIPPING POINT or THEME / THESIS or INVESTMENT INSIGHT |

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

||

WEEKEND FOCUS

Vehicle: CRUDE WEAKENESS

SII OIL Weekly Dec 23, 2014 by TRIGGERS.ca on TradingView.com � |

|||

Is Energy's Dead Cat Bounce Over?

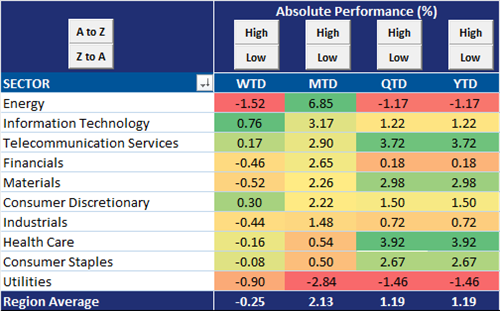

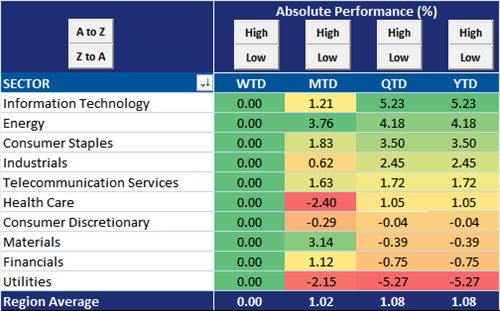

On an equal-weighted basis, the energy sector has still been the best performing sector in February. It is nearly 7% higher this month, however, it has been the worst performing sector so far this week (-1.5%).

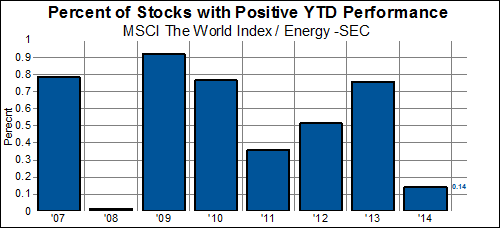

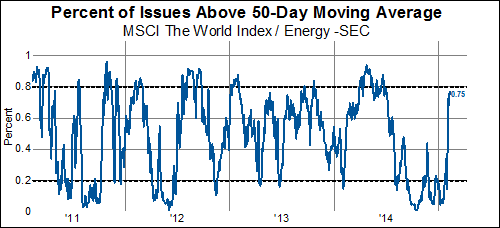

MSCI World Index Performance By Sector  Only 14% of energy stocks are positive this year but shorter term momentum has improved. Unfortunately, it has improved to the point where momentum tends to stall out. 75% of energy stocks are now trading above its 50-day moving average. 80% tends to be an unsustainable level for very long.

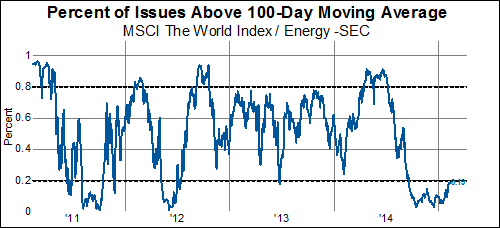

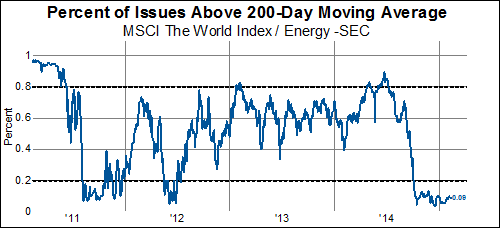

Longer term momentum still looks pretty weak. Only 19% of energy stocks are trading above its 100-day moving average and only 9% of stocks are trading above its 200-day moving average.

Lastly, only 6% of stocks have a 50-day moving average trading above its 200-day moving average. This series needs to turn higher before we would feel confident that the bearish trend in energy stocks has turned. In the chart below we chart this series against the six month returns of the MSCI Energy sector.  |

02-14-15 | SII | |

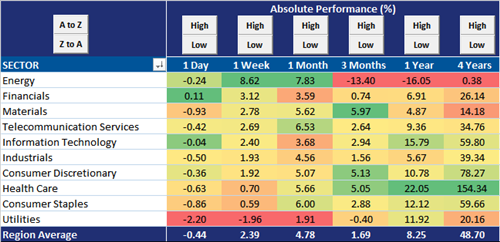

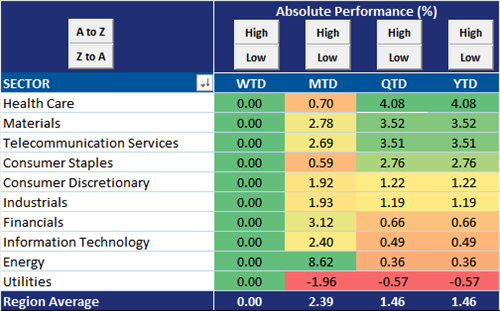

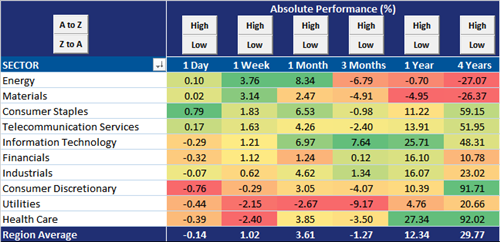

Big Cyclical Bounce Last Week (Week of Feb 02) Led By EnergyWe had a big bounce in cyclical sectors last week in the MSCI World Index. On an equal-weighted basis, the energy sector outperformed the MSCI World Index by over 6% last week. The second best performing sector was financials (+3.12%) and the the third best performing sector was materials (+2.78%). The bottom of the leader board is made up of counter-cyclical sectors. Utilities was the only sector that finished the week in the red (-1.96%), while consumer staples (+0.59%) and health care (+0.70%) rounded out the laggards. Year-to-date, health care remains the best performing sector (+4.08%) and energy (+0.36) has finally moved out of last place and into positive territory for the year. Utilities (-0.57%) has been the worst performing sector so far in 2015. MSCI World Index Performance By Sector  MSCI World Index Performance By Sector  The performance story in the emerging markets last week was similar, it just wasn't as extreme. Energy (+3.16%) was the best performing sector followed closely by materials (+3.14%). However, the third best performing sector was a counter-cyclical sector. Consumer staples ended the week 1.83% higher. The average stock in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index ended the week 1.02% higher. The worst performing sector last week was health care (-2.40%) followed by utilities (-2.15%). Year-to-date, information technology (+5.23%) is the best performing sector followed by energy (+4.18%) and consumer staples (+3.5%). Utilities is by far the worst performing sector in the emerging markets. It is down 5.27% so far this year while the second worst performing sector, financials, is only down 0.75%. MSCI Emerging Markets Index Performance By Sector  MSCI Emerging Markets Index Performance By Sector

|

02-14-15 | SII | |

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - Feb. 8th, 2015 - Feb. 14th, 2015 | |||

| RISK REVERSAL | 1 | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 2 | ||

| BOND BUBBLE | 3 | ||

US ECONOMY - Global Currency Wars & Deflationary Pressures Hoisington Quarterly Review and Outlook – Fourth Quarter 2014

Deflation“No stock-market crash announced bad times. The depression rather made its presence felt with the serial crashes of dozens of commodity markets. To the affected producers and consumers, the declines were immediate and newsworthy, but they failed to seize the national attention. Certainly, they made no deep impression at the Federal Reserve.” Thus wrote author James Grant in his latest thoroughly researched and well-penned book, The Forgotten Depression (1921: The Crash That Cured Itself). Commodity price declines were the symptom of sharply deteriorating economic conditions prior to the 1920-21 depression. To be sure, today’s economic environment is different. The world economies are not emerging from a destructive war, nor are we on the gold standard, and U.S. employment is no longer centered in agriculture and factories (over 50% in the U.S. in 1920). The fact remains, however, that global commodity prices are in noticeable retreat. Since the commodity index peak in 2011, prices have plummeted. The Reuters/Jefferies/CRB Future Price Index has dropped 39%. The GSCI Nearby Commodity Index is down 48% (Chart 1), with energy (-56%), metals (-36%), copper (-40%), cotton (-73%), WTI crude (-57%), rubber (-72%), and the list goes on. In some cases this broad-based retreat reflects increased supply, but more clearly it indicates weakening global demand. The proximate cause for the current economic maladies and continuing downshift of economic activity has been the over-accumulation of debt. In many cases debt funded the purchase of consumable and non-productive assets, which failed to create a future stream of revenue to repay the debt. This circumstance means that existing and future income has to cover, not only current outlays, but also past expenditures in the form of interest and repayment of debt. Efforts to spur spending through relaxed credit standards, i.e. lower interest rates, minimal down payments, etc., to boost current consumption, merely adds to the total indebtedness. According to Deleveraging? What Deleveraging? (Geneva Report on the World Economy, Report 16) total debt to GDP ratios are 35% higher today than at the initiation of the 2008 crisis. The increase since 2008 has been primarily in emerging economies. Since debt is the acceleration of current spending in lieu of future spending, the falling commodity prices (similar to 1920) may be the key leading indicator of more difficult economic times ahead for world economic growth as the current overspending is reversed. Currency ManipulationRecognizing the economic malaise, various economies, including that of the U.S., have instituted policies to take an increasing “market share” from the world’s competitive, slow growing marketplace. The U.S. fired an early shot in this economic war instituting the Federal Reserve’s policy of quantitative easing. The Fed’s balance sheet expansion placed downward pressure on the dollar thereby improving the terms of trade the U.S. had with its international partners (Chart 2). Subsequently, however, Japan and Europe joined the competitive currency devaluation race and have managed to devalue their currencies by 61% and 21%, respectively, relative to the dollar. Last year the dollar appreciated against all 31 of the next largest economies. Since 2011 the dollar has advanced 19%, 15% and 62%, respectively, against the Mexican Peso, the Canadian Dollar and the Brazilian Real. Latin America’s third largest economy, Argentina, and the 15th largest nation in the world, Russia, have depreciated by 115% and 85%, respectively, since 2011. The competitive export advantages gained by these and other countries will have adverse repercussions for the U.S. economy in 2015 and beyond. Historical experience in the period from 1926 to the start of World War II (WWII) indicates this process of competitive devaluations

As a reminder of the pernicious impact of unilateral currency manipulation on global growth, a brief review of the last episode is enlightening. The Currency Wars of the 1920s and 1930sThe return of the French franc to the gold standard at a considerably depreciated level in 1926 was a seminal event in the process of actual and de facto currency devaluations, which lasted from that time until World War II. Legally, the franc’s value was not set until 1928, but effectively the franc was stabilized in 1926. France had never been able to resolve the debt overhang accumulated during World War I and, as a result, had been beset by a series of serious economic problems. The devalued franc allowed economic conditions in France to improve as a result of a rising trade surplus. This resulted in a considerable gold inflow from other countries into France. Moreover, the French central bank did not allow the gold to boost the money supply, contrary to the rules of the game of the old gold standard. A debate has ensued as to whether this policy was accidental or intentional, but it misses the point. France wanted and needed the trade account to continue to boost its domestic economy, and this served to adversely affect economic growth in the UK and Germany. The world was lenient to a degree toward the French, whose economic problems were well known at the time. In the aftermath of the French devaluation, between late 1927 and mid-1929, economic conditions began to deteriorate in other countries. Australia, which had become extremely indebted during the 1920s, exhibited increasingly serious economic problems by late 1927. Similar signs of economic distress shortly appeared in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Finland, Brazil, Poland, Canada and Argentina. By the fall of 1929, economic conditions had begun to erode in the United States, and the stock market crashed in late October. Additionally, in 1929 Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil devalued their currencies and left the gold standard. Australia, New Zealand and Venezuela followed in 1930. Throughout the turmoil of the late 1920s and early 1930s, the U.S. stayed on the gold standard. As a result, the dollar’s value was rising, and the trade account was serving to depress economic activity and transmit deflationary forces from the global economy into the United States. By 1930 the pain in the U.S. had become so great that a de facto devaluation of the dollar occurred in the form of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, even as the United States remained on the gold standard. By shrinking imports to the U.S., this tariff had the same effect as the earlier currency devaluations. Over this period, other countries raised tariffs and/or imposed import quotas. This is effectively equivalent to currency depreciation. These events had consequences. In 1931, 17 countries left the gold standard and/or substantially devalued their currencies. The most important of these was the United Kingdom (September 19, 1931). Germany did not devalue, but they did default on their debt and they imposed severe currency controls, both of which served to contract imports while impairing the finances of other countries. The German action was undeniably more harmful than if they had devalued significantly. In 1932 and early 1933, eleven more countries followed. From April 1933 to January 1934, the U.S. finally devalued the dollar by 59%. This, along with a reversal of the inventory cycle, led to a recovery of the U.S. economy but at the expense of trade losses and less economic growth for others. One of the first casualties of this action was China. China, on a silver standard, was forced to exit that link in September 1934, which resulted in a sharp depreciation of the Yuan. Then in March 1935, Belgium, a member of the gold bloc countries, devalued. In 1936, France, due to massive trade deficits and a large gold outflow, was forced to once again devalue the franc. This was a tough blow for the French because of the draconian anti-growth measures they had taken to support their currency. Later that year, Italy, another gold bloc member, devalued the gold content of the lira by the identical amount of the U.S. devaluation. Benito Mussolini’s long forgotten finance minister said that the U.S. devaluation was economic warfare. This was a highly accurate statement. By late 1936, Holland and Switzerland, also members of the gold bloc, had devalued. Those were just as bitter since the Dutch and Swiss used strong anti- growth measures to try to reverse trade d eficits and the resultant gold outflow. The process came to an end, when Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, as WWII began. It is interesting to ponder the ultimate outcome of this process, which ended with World War II. The extreme over-indebtedness, which precipitated the process, had not been reversed. Thus, without WWII, this so-called “race to the bottom” could have continued on for years. In the United States, the war permitted the debt overhang of the 1920s to be corrected. Unlike the 1930s, the U.S. could now export whatever it was able to produce to its war torn allies. The income gains from these huge net trade surpluses were not spent as a result of mandatory rationing, which the public tolerated because of almost universal support for the war effort. The personal saving rate rose as high as 28%, and by the end of the war U.S. households and businesses had a clean balance sheet that propelled the postwar economic boom. The U.S., in turn, served as the engine of growth for the global economy and gradually countries began to recover from the effects of the Great Depression and World War II. During the late 1950s and 1960s, recessions did occur but they were of the simple garden-variety kind, mainly inventory corrections, and they did not sidetrack a steady advance of global standards of living. 2015As noted above, economic conditions, framework and circumstances are different today. The gold standard in place in the 1920s has been replaced by the fiat currency regime of today. Additionally, imbalances from World War I that were present in the 1920s are not present today, and the composition of the economy is different. Unfortunately, there are parallels to that earlier period.

Clearly the policies of yesteryear and the present are forms of “beggar-my-neighbor” policies, which The MIT Dictionary of Modern Economics explains as follows: “Economic measures taken by one country to improve its domestic economic conditions ... have adverse effects on other economies. A country may increase domestic employment by increasing exports or reducing imports by ... devaluing its currency or applying tariffs, quotas, or export subsidies. The benefit which it attains is at the expense of some other country which experiences lower exports or increased imports ... Such a country may then be forced to retaliate by a similar type of measure.” The existence of over-indebtedness, and its resulting restraint on growth and inflation, has forced governments today, as in the past, to attempt to escape these poor economic conditions by spurring their exports or taking market share from other economies. As shown above, it is a fruitless exercise with harmful side effects. Interest RatesThe downward pressure on global economic growth rates will remain in place in 2015. Therefore record low inflation and interest rates will continue to be made around the world in the new year, as governments utilize policies to spur growth at the expense of other regions. The U.S. will not escape these forces of deflationary commodity prices, a worsening trade balance and other foreign government actions. U.S. nominal GDP in this economic expansion since 2008 has experienced the longest period of slow growth of any recovery since WWII (Chart 3). Typical of the disappointing expansion, the fourth quarter to fourth quarter growth rate slowed from 4.6% in 2013 to 3.8% in 2014. A further slowing of nominal economic growth to around 3% will occur over the four quarters of 2015. The CPI will subside from the 0.8% level for the period December 2013 to December 2014 (Chart 4), registering only a minimal positive change for 2015. Conditions will be sufficiently lackluster that the Federal Reserve will have little choice in their overused bag of tricks but to stand pat and watch their previous mistakes filter through to worsening economic conditions. Interest rates will of course be volatile during the year as expectations shift, yet the low inflationary environment will bring about new lows in yields in 2015 in the intermediate- and long-term maturities of U.S. Treasury securities.

Van R. Hoisington

|

02-12-15 | 3- Bond Bubble | |

DEBT -Debt is a promise of something of value in the future The Problem Of Debt As We Reach Oil Limits 02-11-15 Submitted by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog, via ZH (This is Part 3 of my series – A New Theory of Energy and the Economy. These are links to Part 1 and Part 2.) Many readers have asked me to explain debt. They also wonder, “Why can’t we just cancel debt and start over?” if we are reaching oil limits, and these limits threaten to destabilize the system. To answer these questions, I need to talk about the subject of promises in general, not just what we would call debt. In some sense, debt and other promises are what hold together our networked economy. Debt and other promises allow division of labor, because each person can “pay” the others in the group for their labor with a promise of some sort, rather than with an immediate payment in goods. The existence of debt allows us to have many convenient forms of payment, such as dollar bills, credit cards, and checks. Indirectly, the many convenient forms of payment allow trade and even international trade. Figure 1. Dome constructed using Leonardo Sticks Each debt, and in fact each promise of any sort, involves two parties. From the point of view of one party, the commitment is to pay a certain amount (or certain amount plus interest). From the point of view of the other party, it is a future benefit–an amount available in a bank account, or a paycheck, or a commitment from a government to pay unemployment benefits. The two parties are in a sense bound together by these commitments, in a way similar to the way atoms are bound together into molecules. We can’t get rid of debt without getting rid of the benefits that debt provides–something that is a huge problem. There has been much written about past debt bubbles and collapses. The situation we are facing today is different. In the past, the world economy was growing, even if a particular area was reaching limits, such as too much population relative to agricultural land. Even if a local area collapsed, the rest of the world could go on without them. Now, the world economy is much more networked, so a collapse in one area affects other areas as well. There is much more danger of a widespread collapse. Our economy is built on economic growth. If the amount of goods and services produced each year starts falling, then we have a huge problem. Repaying loans becomes much more difficult. Figure 2. Repaying loans is easy in a growing economy, but much more difficult in a shrinking economy. In fact, in an economic contraction, promises that aren’t debt, such as promises to pay pensions and medical costs of the elderly as part of our taxes, become harder to pay as well. The amount we have left over for discretionary expenditures becomes much less. These pressures tend to push an economy further toward contraction, and make new promises even harder to repay. The Nature of Debt In a broad sense, debt is a promise of something of value in the future. With this broad definition, it is clear that a $10 bill is a form of debt, because it is a promise that at some point in the future you, or the person you pass the $10 bill on to, will be able to exchange the $10 bill for something of value. In a sense, even gold coins are a promise of value in the future. This is not necessarily a promise we can count on though. At times in the past, gold coins have been confiscated. Derivatives and other financial products have characteristics of debt as well. To understand how important debt is, we need to think about an economy without debt. Such an economy might have a central market where everyone brings goods to exchange. But even in such an economy, there will be a problem if there is not a precise matching of needs. If I bring apples and you bring potatoes, we could exchange with each other (“barter”). But what if I don’t have a need for potatoes? Then we might need to bring a third person into the ring, so each of us can receive what we want. Because barter is so cumbersome, barter was never widely used for everyday transactions within communities. An approach that seemed to work better is one mentioned in David Graeber’s book, Debt: The First 5,000 Years. With this system, a temple would operate a market. The operator of the market would provide a “price” for each object, in terms of a common unit, such as “bushels of wheat.” Each person could bring goods to the market (and perhaps even services–I will work for a day in your vineyard), and have them exchanged with others based on value. No “money” was really needed because the operator would take a clay tablet and on it make a calculation of the value in “bushels of wheat” of what a person brought in goods, The operator would also calculate the value in “bushels of wheat” that the same person was receiving in return, and make certain that the two matched. Of course, as soon as we start allowing “a day’s worth of labor ” to be exchanged in this way, we get back to the problem of future promises, and making certain that they really happen. Also, if we allow a person to carry over a balance from one day to another–for example, bringing in a large quantity of goods that cannot be sold in one day–then we get into the area of future promises. Or if we allow a farmer to buy seed on credit, with a promise to pay it back when harvest comes in a few months, we again get into the area of future promises. So even in this simple situation, we need to be able to handle the issue of future promises. Future Promises Even Before Debt Whenever there is division of labor, there needs to be some agreement as to how that division will take place–what are the responsibilities of each participant. In the simplest case, we have hunters and gatherers. If there is a decision that the men will do the hunting and the women will do the gathering and care for children, then there needs to be an agreement as to how the arrangement will work. The usual approach seems to have been some sort of “gift economy.” In such an economy, everyone would share whatever they were able to obtain with others, and would gain status by the amount they could offer to share. Instead of a formal debt being involved, there was an understanding that if people were to participate in the group, they had to follow the rules that the particular culture dictated, including, very often, sharing everything. People who didn’t follow the rules would be thrown out. Because of the difficulty in living in such an environment alone, such people would likely die. Thus, participants were in some sense bound together by the customs that underlay gift economies. At some point, as more of an economy was built up, there would be a need for one or more leaders, as well as some way of financially supporting those leaders. Thus, there would need to be some sort of taxation. While taxation to support the leader would not be considered debt, it has many of the same characteristics as debt. It is an ongoing payment obligation. The leader and the other members of the group plan their lives as if this situation is going to continue. In a way, the governmental services and the resulting taxation help bind the economy together. Benefits of Debt The benefits of debt are truly great, including the following:

What Goes Wrong with Debt and Other Financial Promises 1. As mentioned at the beginning of the post, debt works very badly if the economy is contracting. It becomes impossible to repay debt with interest, without reducing discretionary income. Government programs, such as health care for the elderly, become more expensive relative to current incomes as well. 2. Interest payments on debt tend to transfer wealth from the poorer members of society to the richer members of society. Economists have tended to ignore debt, because it represents a more or less balanced transaction between two individuals. The fact remains, though, that the poorer members of society find themselves especially in need of debt, and many pay very high interest rates. The ones lending money tend to be richer. Because of this arrangement, over time, interest payments tend to increase wealth disparities. 3. All too often, the payment stream upon which debt depends proves unsustainable. In the example given above, everyone thinks the North Dakota oil will continue for a while, so takes out loans as if this is the case. If it doesn’t, then this is an “Oops” situation. In the case of US student loans, many students are never able to get jobs with high enough wages to pay back the loans they were given. 4. Governments tend to put programs into place that are more expensive than they really can afford, for the long term. As an economy gets wealthier (because of more fossil fuel use), there is a tendency to add more programs. Representative government is used instead of a monarch. Medical care and pensions for the elderly are added, as are unemployment benefits, and more advanced levels of schools. Unfortunately, it is hard to properly estimate what long-run cost of these programs will be. Also, even if the programs were affordable with a high level of fossil fuels, they almost certainly will not be affordable if energy availability declines. It is virtually impossible to roll programs back, even if they are not guaranteed, once people plan their lives on the new programs. Figure 3 shows a graph of US government spending (all levels) compared to wages (including amounts paid to proprietors, including farmers). I use this base, rather than GDP, because wages have not been keeping up with GDP in recent years. The amounts shown include programs such as Social Security and Medicare for the elderly, in addition to spending on things such as schools, roads, and unemployment insurance. Figure 3. Comparison of US Government spending and receipts (all levels combined) based on US Bureau of Economic Research Data. Clearly, government spending has been rising much faster than wages. I would expect this to be true in many countries. 5. There is no real tie between amounts of debt issued and what will actually be produced in the future. We are told that money is a store of value, and that it transfers purchasing power from the present to the future. In other words, we can count on balances in our bank accounts, and in fact, in all of the paper securities that are outstanding. This story is only true if the economy can continue to create an increasing amount of goods and services forever. If, in fact, the production of goods and services drops off dramatically (most likely because prices cannot rise high enough to encourage enough extraction of commodities), then we have a major problem. In any year, all we have available is the actual amount of resources that can be pulled out of the ground, plus the actual amount of food that can be grown. Together, these amounts determine how many goods and services are available. Money acts to distribute the goods that are available. Presumably, the people who work at extraction and production of these goods and services need to be paid first, or the whole process will stop. This basically leaves the “leftovers” to be shared among those who are now being supported by tax revenue and by those who hold paper securities of some sort or other. It is hard to see that anyone other than the workers producing the goods and services will get very much, if we lose the use of fossil fuels. Workers will become less efficient, and production will drop by too much. 6. Derivatives and other financial products expose the financial system to significant risks. Certain large banks have found that they can earn considerable revenue by selling derivatives and other financial products, allowing people or businesses to essentially gamble on certain outcomes–such as the price of oil falling below a certain price, or interest rates rising very rapidly, or a certain company failing. As long as everything goes well, there is not a huge problem. The concern now is that with rapidly changing commodity prices, and rapidly changing levels of currencies, companies may fail and there may be major payouts triggered. In theory, some of these payments may be offsetting–money owed by one client may offset money owed to another client. But even if this is the case, these defaults can sometimes take years to settle. There may also be issues with one of the parties’ ability to pay. One particular problem with many of the products is the use of the Black-Scholes Pricing Model. This model is applicable when events are independent and normally distributed. This is not the case, when we are approaching oil limits and other limits of a finite world. 7. Governments tend to be badly affected by a shrinking economy, so may be of little assistance when we need them most. As noted previously, payments to governments act very much like debt. As an economy shrinks, programs that seemed affordable in the past become less affordable and badly need to be cut. Thus, governments tend to have problems at the exactly same time that banks and other lenders do. Governments of “advanced” countries now have debt levels that are high by historical standards. If there is another major financial crisis, the plan seems to be to use Cyprus-like bail-ins of banks, instead of bailing out banks using government debt. In a bail-in, bank deposits are exchanged for equity in the failing bank. For example, in Cyprus, 37.5% of deposits in excess of 100,000 euros were converted to Class A shares in the bank. This approach has a lot of difficulties. Businesses have a need for their funds, for purposes such as paying employees and building new factories. If their funds are taken in a bail-in, the ability of the business to continue may be damaged. Individual consumers depend on their bank balances as well. As noted above, deposit insurance is theoretically available, but the actual amount of funds for this purpose is very low relative to the amount potentially at risk. So we get back to the issue of whether governments can and will be able to bail out banks and other failing financial institutions. 8. More debt is needed to hide the lack of economic growth in an ailing world economy. This debt becomes increasingly difficult to obtain, as wages stagnate because of diminishing returns. If wages are rising fast enough, wages by themselves might be used to pump demand for commodities, and thus raise their prices. Our wages are close to flat–median wages have been falling in the US. If wages aren’t rising sufficiently, increasing debt must be used to raise demand. Debt is growing slowly in the household sector, according to figures compiled by McKinsey Global Institute. Household debt has grown by only 2.8% per year between Q4 2007 and Q4 2014, compared to 8.5% per year in the period between Q4 2000 and Q4 2007. Even with business demand included, debt isn’t rising rapidly enough to keep commodity prices up. This lack of sufficient growth in debt (and lack of growth in demand apart from growing debt) seems to be a major reason for the drop in prices since 2011 in many commodity prices. 9. Differing policies with respect to interest rates and quantitative easing seem to have the possibility of tearing the world financial system apart. In a networked economy, not moving too far from the status quo is a definite advantage. If the US’s policies have the effect of raising the value of the dollar, and the policies of other countries have the tendency to lower their currencies, the net effect is to make debt held in other countries but denominated in US dollars unpayable. It also makes goods sold by American companies unaffordable. The economy, as it exists today, has been made possible by countries working together. With sanctions against Iran and Russia, we are already moving away from this situation. Low oil prices are now putting the economies of oil exporters at risk. As countries try different approaches on interest rates, this adds yet another force, pulling economies apart. 10. The economy begins to act very strangely when too much of current income is locked up in debt and debt-like instruments. Economic models suggest that if oil prices drop, demand for oil will grow robustly and supply will drop off quickly. If oil producers are protected by futures contracts that lock in a high price, they may not respond in the manner expected. In fact, if they are obligated to make debt payments, they may continue drilling even when it may not otherwise make financial sense to do so. Likewise, consumers are also affected by prior commitments. If much of consumers’ income is tied up with condominium payments, auto payments, and payment of taxes, they may not have much ability to respond to lower oil prices. Instead of increasing discretionary spending, consumers may pay off some of their debt with their newfound income. Conclusion If the current economic system crashes and it becomes necessary to create a new one, the new system will have to deal with having an ever-smaller amount of goods and services available for a fairly long transition time. Because of this, the new system will have to be very different from the current one. Most promises will need to be of short duration. Transfers among people living in a particular area might still be facilitated by a financial system, but it would be hard to have long-term or long-distance contracts. As a result, the new economy will likely need to be much simpler than our current economy. It is doubtful it could include fossil fuels. Many people ask why we can’t just cancel all debt, and start over again. To do so would probably mean canceling all bank accounts as well. Most of our current jobs would probably disappear. We would probably be without grid electricity and without oil for cars. It would be very difficult to start over from such a situation. We would truly have to start over from scratch. I have not talked about a distinction between “borrowed funds” and “accumulated equity”. Such a distinction is important in terms of the rate of return investors expect, but it is not as important in a crash situation. Similarly, the difference between stocks, bonds, pension plans, and insurance contracts becomes less important as well. If there are real problems, anything that is not physical ends up in the general category of “paper wealth”. We cannot count on paper wealth (or for that matter, any wealth) for the long term. Each year, the amount of goods and services the economy can produce is limited by how the economy is performing, given limits we are reaching. If the quantity of these goods and services starts falling rapidly, governments may fail in addition to our problems with debts defaulting. Those holding paper wealth can’t count on getting very much. Workers producing whatever goods and services are actually being produced will likely need to be paid first. |

02-12-15 | 3- Bond Bubble | |

EU BANKING CRISIS |

4 |

||

| SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS [Euope Crisis Tracker] | 5 | ||

CHINA BUBBLE |

6 | ||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

| STUDIES - MACRO pdf | |||

EARNINGS - Another Year End Hockey Stock - That Never Materialize DOES ANLYONE ACTUALLY BELIEVE THESE FORECASTS?

FACTS:

REMEMBER THIS? and to put Apple Into Perspective

WALL STREET TRACK RECORD

|

02-11-15 | EARNINGS | |

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| THESIS | |||

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

"There is no FREEDOM without NOISE - and no STABILITY without VOLATILITY."

Painting by Anthony Freda 42 ADMITTED False Flag Attacks 02-08-15

So Common … There’s a Name for ItThe use of the bully’s trick is so common that it was given a name hundreds of years ago. “False flag terrorism” is defined as a government attacking its own people, then blaming others in order to justify going to war against the people it blames. Or as Wikipedia defines it:

The term comes from the old days of wooden ships, when one ship would hang the flag of its enemy before attacking another ship. Because the enemy’s flag, instead of the flag of the real country of the attacking ship, was hung, it was called a “false flag” attack. Indeed, this concept is so well-accepted that rules of engagement for naval, air and land warfare all prohibit false flag attacks. Leaders Throughout History Have Acknowledged False FlagsLeaders throughout history have acknowledged the danger of false flags:

Governments from Around the World Admit They Do ItThere are many documented false flag attacks, where a government carries out a terror attack … and then falsely blames its enemy for political purposes. In the following 42 instances, officials in the government which carried out the attack (or seriously proposed an attack) admits to it, either orally or in writing: (1) Japanese troops set off a small explosion on a train track in 1931, and falsely blamed it on China in order to justify an invasion of Manchuria. This is known as the “Mukden Incident” or the “Manchurian Incident”. The Tokyo International Military Tribunal found: “Several of the participators in the plan, including Hashimoto [a high-ranking Japanese army officer], have on various occasions admitted their part in the plot and have stated that the object of the ‘Incident’ was to afford an excuse for the occupation of Manchuria by the Kwantung Army ….” And see this. (2) A major with the Nazi SS admitted at the Nuremberg trials that – under orders from the chief of the Gestapo – he and some other Nazi operatives faked attacks on their own people and resources which they blamed on the Poles, to justify the invasion of Poland. (3) Nazi general Franz Halder also testified at the Nuremberg trials that Nazi leader Hermann Goering admitted to setting fire to the German parliament building in 1933, and then falsely blaming the communists for the arson. (4) Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev admitted in writing that the Soviet Union’s Red Army shelled the Russian village of Mainila in 1939 – while blaming the attack on Finland – as a basis for launching the “Winter War” against Finland. Russian president Boris Yeltsin agreed that Russia had been the aggressor in the Winter War. (5) The Russian Parliament, current Russian president Putin and former Soviet leader Gorbachev all admit that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered his secret police to execute 22,000 Polish army officers and civilians in 1940, and falsely blame it on the Nazis. (6) The British government admits that – between 1946 and 1948 – it bombed 5 ships carrying Jews attempting to flee the Holocaust to seek safety in Palestine, set up a fake group called “Defenders of Arab Palestine”, and then had the psuedo-group falsely claim responsibility for the bombings (and see this, this and this). (7) Israel admits that in 1954, an Israeli terrorist cell operating in Egypt planted bombs in several buildings, including U.S. diplomatic facilities, then left behind “evidence” implicating the Arabs as the culprits (one of the bombs detonated prematurely, allowing the Egyptians to identify the bombers, and several of the Israelis later confessed) (and see this and this). (8) The CIA admits that it hired Iranians in the 1950′s to pose as Communists and stage bombings in Iran in order to turn the country against its democratically-elected prime minister. (9) The Turkish Prime Minister admitted that the Turkish government carried out the 1955 bombing on a Turkish consulate in Greece – also damaging the nearby birthplace of the founder of modern Turkey – and blamed it on Greece, for the purpose of inciting and justifying anti-Greek violence. (10) The British Prime Minister admitted to his defense secretary that he and American president Dwight Eisenhower approved a plan in 1957 to carry out attacks in Syria and blame it on the Syrian government as a way to effect regime change. (11) The former Italian Prime Minister, an Italian judge, and the former head of Italian counterintelligence admit thatNATO, with the help of the Pentagon and CIA, carried out terror bombings in Italy and other European countries in the 1950s and blamed the communists, in order to rally people’s support for their governments in Europe in their fight against communism. As one participant in this formerly-secret program stated: “You had to attack civilians, people, women, children, innocent people, unknown people far removed from any political game. The reason was quite simple. They were supposed to force these people, the Italian public, to turn to the state to ask for greater security” (and see this) (Italy and other European countries subject to the terror campaign had joined NATO before the bombings occurred). And watch this BBC special. They also allegedly carried out terror attacks in France, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the UK, and other countries. (12) In 1960, American Senator George Smathers suggested that the U.S. launch “a false attack made on Guantanamo Bay which would give us the excuse of actually fomenting a fight which would then give us the excuse to go in and [overthrow Castro]“. (13) Official State Department documents show that, in 1961, the head of the Joint Chiefs and other high-level officialsdiscussed blowing up a consulate in the Dominican Republic in order to justify an invasion of that country. The plans were not carried out, but they were all discussed as serious proposals. (14) As admitted by the U.S. government, recently declassified documents show that in 1962, the American Joint Chiefs of Staff signed off on a plan to blow up AMERICAN airplanes (using an elaborate plan involving the switching of airplanes), and also to commit terrorist acts on American soil, and then to blame it on the Cubans in order to justify an invasion of Cuba. See the following ABC news report; the official documents; and watch this interview with the former Washington Investigative Producer for ABC’s World News Tonight with Peter Jennings. (15) In 1963, the U.S. Department of Defense wrote a paper promoting attacks on nations within the Organization of American States – such as Trinidad-Tobago or Jamaica – and then falsely blaming them on Cuba. (16) The U.S. Department of Defense even suggested covertly paying a person in the Castro government to attack the United States: “The only area remaining for consideration then would be to bribe one of Castro’s subordinate commanders to initiate an attack on Guantanamo.” (17) The NSA admits that it lied about what really happened in the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964 … manipulating data to make it look like North Vietnamese boats fired on a U.S. ship so as to create a false justification for the Vietnam war. (18) A U.S. Congressional committee admitted that – as part of its “Cointelpro” campaign – the FBI had used many provocateurs in the 1950s through 1970s to carry out violent acts and falsely blame them on political activists. (19) A top Turkish general admitted that Turkish forces burned down a mosque on Cyprus in the 1970s and blamed it on their enemy. He explained: “In Special War, certain acts of sabotage are staged and blamed on the enemy to increase public resistance. We did this on Cyprus; we even burnt down a mosque.” In response to the surprised correspondent’s incredulous look the general said, “I am giving an example”. (20) The German government admitted (and see this) that, in 1978, the German secret service detonated a bomb in the outer wall of a prison and planted “escape tools” on a prisoner – a member of the Red Army Faction – which the secret service wished to frame the bombing on. (21) A Mossad agent admits that, in 1984, Mossad planted a radio transmitter in Gaddaffi’s compound in Tripoli, Libya which broadcast fake terrorist trasmissions recorded by Mossad, in order to frame Gaddaffi as a terrorist supporter. Ronald Reagan bombed Libya immediately thereafter. (22) The South African Truth and Reconciliation Council found that, in 1989, the Civil Cooperation Bureau (a covert branch of the South African Defense Force) approached an explosives expert and asked him “to participate in an operation aimed at discrediting the ANC [the African National Congress] by bombing the police vehicle of the investigating officer into the murder incident”, thus framing the ANC for the bombing. (23) An Algerian diplomat and several officers in the Algerian army admit that, in the 1990s, the Algerian army frequently massacred Algerian civilians and then blamed Islamic militants for the killings (and see this video; and Agence France-Presse, 9/27/2002, French Court Dismisses Algerian Defamation Suit Against Author). (24) An Indonesian fact-finding team investigated violent riots which occurred in 1998, and determined that “elements of the military had been involved in the riots, some of which were deliberately provoked”. (25) Senior Russian Senior military and intelligence officers admit that the KGB blew up Russian apartment buildings in 1999 and falsely blamed it on Chechens, in order to justify an invasion of Chechnya (and see this report and this discussion). (26) According to the Washington Post, Indonesian police admit that the Indonesian military killed American teachers in Papua in 2002 and blamed the murders on a Papuan separatist group in order to get that group listed as a terrorist organization. (27) The well-respected former Indonesian president also admits that the government probably had a role in the Bali bombings. (28) As reported by BBC, the New York Times, and Associated Press, Macedonian officials admit that the government murdered 7 innocent immigrants in cold blood and pretended that they were Al Qaeda soldiers attempting to assassinate Macedonian police, in order to join the “war on terror”. (29) Senior police officials in Genoa, Italy admitted that – in July 2001, at the G8 summit in Genoa – planted two Molotov cocktails and faked the stabbing of a police officer, in order to justify a violent crackdown against protesters. (30) Although the FBI now admits that the 2001 anthrax attacks were carried out by one or more U.S. government scientists, a senior FBI official says that the FBI was actually told to blame the Anthrax attacks on Al Qaeda by White House officials (remember what the anthrax letters looked like). Government officials also confirm that the white House tried to link the anthrax to Iraq as a justification for regime change in that country. (31) Similarly, the U.S. falsely blamed Iraq for playing a role in the 9/11 attacks – as shown by a memo from the defense secretary – as one of the main justifications for launching the Iraq war. Even after the 9/11 Commission admitted that there was no connection, Dick Cheney said that the evidence is “overwhelming” that al Qaeda had a relationship with Saddam Hussein’s regime, that Cheney “probably” had information unavailable to the Commission, and that the media was not ‘doing their homework’ in reporting such ties. Top U.S. government officials now admit that the Iraq war was really launched for oil … not 9/11 or weapons of mass destruction (despite previous “lone wolf” claims, many U.S. government officials now say that 9/11 was state-sponsored terror; but Iraq was not the state which backed the hijackers). (32) Former Department of Justice lawyer John Yoo suggested in 2005 that the US should go on the offensive against al-Qaeda, having “our intelligence agencies create a false terrorist organization. It could have its own websites, recruitment centers, training camps, and fundraising operations. It could launch fake terrorist operations and claim credit for real terrorist strikes, helping to sow confusion within al-Qaeda’s ranks, causing operatives to doubt others’ identities and to question the validity of communications.” (33) United Press International reported in June 2005:

(34) Undercover Israeli soldiers admitted in 2005 to throwing stones at other Israeli soldiers so they could blame it on Palestinians, as an excuse to crack down on peaceful protests by the Palestinians. (35) Quebec police admitted that, in 2007, thugs carrying rocks to a peaceful protest were actually undercover Quebec police officers (and see this). (36) At the G20 protests in London in 2009, a British member of parliament saw plain clothes police officers attempting to incite the crowd to violence. (37) Egyptian politicians admitted (and see this) that government employees looted priceless museum artifacts in 2011 to try to discredit the protesters. (38) A Colombian army colonel has admitted that his unit murdered 57 civilians, then dressed them in uniforms and claimed they were rebels killed in combat. (39) The highly-respected writer for the Telegraph Ambrose Evans-Pritchard says that the head of Saudi intelligence – Prince Bandar – recently admitted that the Saudi government controls “Chechen” terrorists. (40) High-level American sources admitted that the Turkish government – a fellow NATO country – carried out the chemical weapons attacks blamed on the Syrian government; and high-ranking Turkish government admitted on tape plans to carry out attacks and blame it on the Syrian government. (41) The former Ukrainian security chief admits that the sniper attacks which started the Ukrainian coup were carried out in order to frame others. (42) Britain’s spy agency has admitted (and see this) that it carries out “digital false flag” attacks on targets, framing people by writing offensive or unlawful material … and blaming it on the target. In addition, two-thirds of the City of Rome burned down in a huge fire on July 19, 64 A.D. The Roman people blamed the Emperor Nero for starting the fire. Some top Roman leaders – including the Roman consul Cassius Dio, as well as historians like Suetonius– agreed that Nero started the fire (based largely on the fact that the Roman Senate had just rejected Nero’s application to clear 300 acres in Rome so that he could build a palatial complex, and that the fire allowed him to build his complex). Regardless of who actually started the fire, Nero – in the face of public opinion accusing him of arson – falsely blamed the Christians for starting the fire. He then rounded up and brutally tortured and murdered scores of Christians for something they likely didn’t do. We didn’t include this in the list above, because – if Nero did start the fire on purpose – he did it for his own reasons (to build his palatial complex), and not for geopolitical reasons benefiting his nation.

|

02-10-15 | THESIS | |

|

2013 2014 |

|||

FINANCIAL REPRESSION - A Failure of Global Governanace

The following was taken from The Template For How the Next Crisis Will Unfold by Graham Summers at Phoenix Capital Research WHAT LIES AHEAD

This is the template for what’s coming. The following is the proof: EUROPE AS THE MODEL Europe is ground zero for the whole debt bomb implosion, not because it has the most debt but because it’s politically and economically on the least sound footing. Some 19 countries share the currency, all of them in varying degrees of socialism (the public sector accounts for roughly 1 in 3 employees in Germany’s allegedly “free market” economy), and varying shades of broke: even Germany a real Debt to GDP of over 200%. In this regard, Europe gives the rest of us a front-row seat to learn how things will unfold when the real stuff hits the fan and the political and financial elite are at risk of losing their power and wealth. We’ve been through this mess multiple times in the last three years. The most notable cases involved Spain and Cyprus. And the formula is as follows:

THE 'BANKIA" EXAMPLE Bankia was formed by merging seven bankrupt regional Spanish banks in 2010. The new bank was funded by Spain’s Government rescue fund… which received “preference shares” in return for over €4 billion in funding for the bank (all provided by taxpayers of course). These preference shares were shares that A) yielded 7.75% and B) would get paid before ordinary investors if Bankia failed again. So right away, the Spanish Government was taking taxpayer money to give itself preferential treatment over ordinary investors (including said taxpayers). Indeed, those investors who owned shares in the seven banks that merged to form Bankia lost their shirts. They were wiped out and lost everything when the new bank was created. Bankia was taken public in 2011. Spanish investment bankers convinced the Spanish public that the bank was a fantastic investment. Over 98% of the shares were sold to Spanish investors. One year later, Bankia was bankrupt again, and required the single largest bailout in Spain’s history: €19 billion. Spain took over the bank (again) and Bankia shares were frozen on the market (meaning you couldn’t sell them if you wanted to). When the bailout took place, Bankia shareholders were all but wiped out and forced to take huge losses as part of the deal. The vast majority of these were individual investors, NOT Wall Street or its European equivalent (Bankia currently faces a lawsuit for over 140,000 claims of mis-selling shares). So that’s two wipeouts in as many years. The bank was taken public a second time in May 2013. Once again Bankia shares promptly collapsed, losing 80% of their value in a matter of days. And once again, it was ordinary investors who got destroyed. Indeed, things were so awful that a police officer stabbed a Bankia banker who sold him over €300,000 worth of shares (the banker had convinced him it was a great investment). Today Bankia is tied up in a massive compensation lawsuit whereby it is to pay out between 200 and 250 million Euros to investors who bought it during its initial IPO. Of course, this payout is based on accounting standards that are at best massaged and at worst likely outright fraudulent (this is, again a bank that has wiped out investors three in times in three years), so who knows what will happen? While certain items relating to this story are unique, the morals to Bankia’s tale can be broadly applied across the board to the economy/ financial today. |

02-09-15 | THESIS GLOBAL GOVERNANCE |

|

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| THEMES | |||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | THEME | ||

FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt Now On The Endangered Species List: Bond Traders 02-02-15 The topic of collapsing bond market liquidity (and in many cases, volume) is not new: it has been covered here for over 3 years, as we observed the amount of 10 Year equivalents soaked up by the Fed week after week and month after month, to the point where even the Treasury department agreed that in its quest to soak up "high quality collateral"... "the Fed is making the bond market dangerously illiquid". It got so bad that in the fourth quarter of last year, the US banks posted the worst collective results across what is typically their most lucrative, Fixed Income Currency and Commodity division, since Lehman. And yet while the bond market may have gotten so fragmented in recent months that even Bloomberg was amazed at how little trading volume it necessary to make a price impact, the amount of bond traders (and certainly salesmen), and certainly their bonuses, appeared to only go up. "Appeared" being the key word, however, because as Bloomberg reports, "the average number of dealers providing prices for European corporate bonds dropped to a low of 3.2 per trade last month, down from 8.8 in 2009, according to data compiled by Morgan Stanley." Curiously, what is happening in the bond market is comparable to parallel developments in stocks, where... "an ever smaller group of companies, with an ever greater market cap (here's looking at you AAPL, AMZN and V), determines the leadership of not only the NASDAQ and the DJIA, but the entire S&P500 itself" A phenomenon we dubbed the "CYNK market", in which prices keep rising on lower and lower volumes, until eventually the selling begins, and since there is nobody to buy (and certainly no shorts left to cover), and hence no liquidity, trading in the security is halted indefinitely, making sure those paper gains remains such in perpetuity. Bloomberg cuts to the chase:

Actually, judging by the record surge in bond-funded buybacks, traders are willing to buy in any case, completely ignorant of the cost of capital, and will gladly hand over "other people's money" to any management team that will ask for it, irrelevant if the "use of proceeds" is simply to pad management's own year-end bonus pool through equity-linked compensation, which in turn is facilitated by a record amount of corporate stock buybacks. Buybacks which, as a reminder according to Goldman, will be major source of stock buying in the S&P 500 now! Call it the CYNK "market", call it the pulling-yourself-by-the-bootstraps "market", just don't call it a market. But enough about bond-funded stock buybacks; back to bonds and bond traders, where one is either being laid off or has extensive opinions on what happens next, ranging from the concerned...

... to the outright idiotic:

Sure: it is all about buying-to-hold... if one is trying to justify a losing position on the books (or to bail out an entire financial system hence the halt of Mark-to-Market across the entire US financial system in the spring of 2009), or if one has an infinite balance sheet such as a central bank. For everyone else, nothing would spur panicked selling like more selling, as the self-fulfilling prophecy of margin call-driven liquidations spreads like wildfire. The problem is that once the selling begins, there will be nobody to buy:

And just like the US housing market, where everything but the ultra-luxury segment is sliding fast all over again with the US middle class on fast-track to extension, so with stocks, i.e., Apple, and with bonds, i.e., Treasurys and the highest rated corps, increasingly more trading and liquidity is only focused on the Top 10 most popular and traded names... then Top 5... then Top 1, until everyone just passes a few "hot potato" securities back and forth to one another, in hopes that one will not be the last one holding said potato when the central bank music stops and the last game of musical chairs ends with tragic consequences. And "one" is also precisely how many traders will be left when it is all said and done. In the meantime, to all the recently and not so recently unemployed bond traders out there who used to worry about the downside: thank the Chief Risk Officer of the capital "markets", the central banks, for eliminating all downside risk in perpetuity or at least until all faith in central bank collapses, but not before your job becomes extinct. Instead, just do like the E-trade baby and shift your attention to stocks. There, the "strategy" is far simpler: just BTFATH.

|

02-13-15 | THEMES | FLOWS |

| SHADOW BANKING -LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | THEME | ||

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | THEME | ||

| ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | THEME | ||

| PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX -NATURE OF WORK | THEME | ||

| STANDARD OF LIVING -EMPLOYMENT CRISIS | THEME | ||

| CORPORATOCRACY -CRONY CAPITALSIM | THEME |  |

|

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE -MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|

| SOCIAL UNREST -INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | THEME | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX -STATISM | THEME | ||

| GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | THEME | ||

| CENTRAL PLANINNG -SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER | THEME | ||

| CATALYSTS -FEAR & GREED | THEME | ||

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

| TO TOP | |||

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP