|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

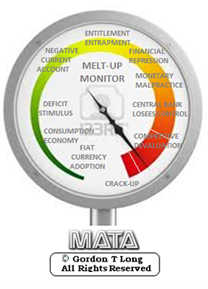

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Tue. Mar. 18th, 2014

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

STRATEGIC MACRO INVESTMENT INSIGHTS

2014 THESIS: GLOBALIZATION TRAP

2014 THESIS: GLOBALIZATION TRAP

NOW AVAILABLE FREE to Trial Subscribers

185 Pages

What Are Tipping Poinits?

Understanding Abstraction & Synthesis

Global-Macro in Images: Understanding the Conclusions

| MARCH | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1 - Risk Reversal |

| 2 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 3- Bond Bubble |

| 4- EU Banking Crisis |

| 5- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 6 - China Hard Landing |

| 7 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 8 - Geo-Political Event |

| 9 - Global Governance Failure |

| 10 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 11 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 12 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 15 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 16 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 17 - Credit Contraction II |

| 18- State & Local Government |

| 19 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 20 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 21 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 22 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 23 - US Reserve Currency |

| 24 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 25 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 26 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 27 - Food Price Pressures |

| 28 - Global Output Gap |

| 29 - Corruption |

| 30 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 31 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 32- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - US Reserve Currency |

| 35- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 36 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 37 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 38 - Terrorist Event |

| 39 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

| 41 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

|

Scroll TWEETS for latest Analysis

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||||

UKRAINE - The Unfolding Financial Battle

|

|||||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

|||||

"BEST OF THE WEEK " |

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags | TIPPING POINT or 2014 THESIS THEME |

||

|

|||||

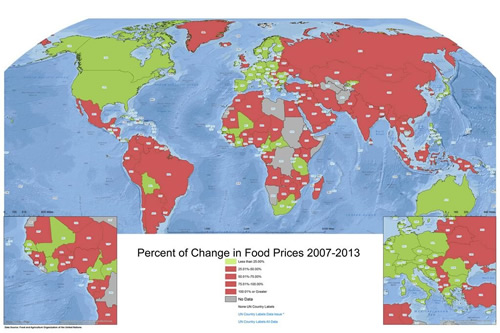

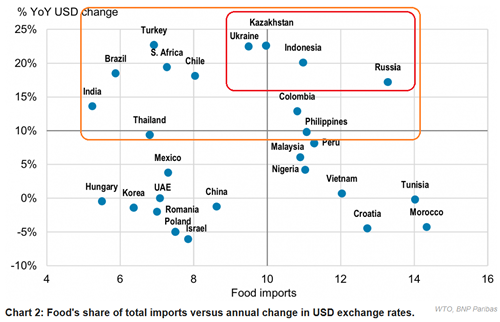

FOOD INFATION - Its Initially Going to Be A Retail CRE and EM Problem There is a Correlation Between Food Price Inflation & Social Unrest

The Ukrainean Breadbasket Has Food Price Pressures

Things Could Potentially Get Worse

|

03-18-14 | GLOBAL RISK FOOD |

27 - Food Price Pressures | ||

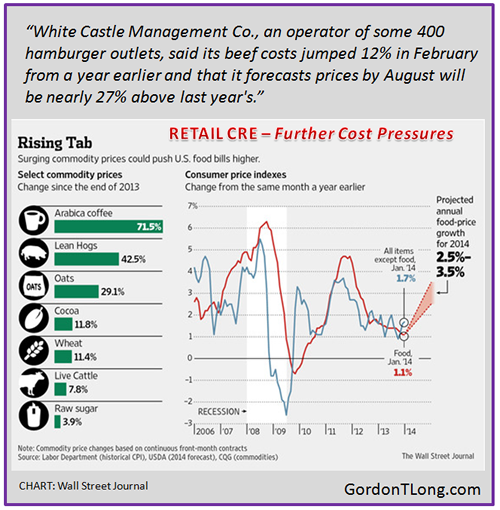

FOOD INFATION - Its Initially Going to Be A Retail CRE and EM Problem Food Prices Surge as Drought Exacts a High Toll on Crops 03-17-14 WSJ Costs Pinch Consumers, Companies Still Grappling With Sluggish Economic Recovery Surging prices for food staples from coffee to meat to vegetables are driving up the cost of groceries in the U.S., pinching consumers and companies that are still grappling with a sluggish economic recovery. Federal forecasters estimate retail food prices will rise as much as 3.5% this year, the biggest annual increase in three years, as drought in parts of the U.S. and other producing regions drives up prices for many agricultural goods. Globally, food inflation has been tame, but economists are watching for any signs of tighter supplies of key commodities such as wheat and rice that could push prices higher. In the U.S., much of the rise in the food cost comes from higher meat and dairy prices, due in part to tight cattle supplies after years of drought in states such as Texas and California and rising milk demand from fast-growing Asian countries. But prices also are higher for fruits, vegetables, sugar and beverages, according to government data. In futures markets, coffee prices have soared so far this year more than 70%, hogs are up 42% on disease concerns and cocoa has climbed 12% on rising demand, particularly from emerging markets. Drought in Brazil, the world's largest producer of coffee, sugar and oranges, has increased coffee prices, while dry weather in Southeast Asia has boosted prices for cooking oils such as palm oil.

Though rising, U.S. food inflation isn't yet near some lofty recent levels. In 2008, food prices jumped 5.5%, the most in 18 years, and they climbed 3.7% in 2011. Inflation also could be tempered if U.S. farmers, as expected, plant large corn and soybean crops this spring and receive favorable weather during the summer. That would hold down feed prices for livestock and poultry, as well as ingredient costs for breakfast cereals and baked goods. The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated last month that retail food prices will rise between 2.5% and 3.5% this year, up from 1.4% last year. The inflation comes despite sharp decreases over the past year in the prices of grains, including corn, after a big U.S. harvest. In other years—notably 2008—surging grain prices were a key contributor to higher food costs. Food prices have gained 2.8%, on average, for the past 10 years, outpacing the increase in prices for all goods, which rose 2.4%, according to the government. Overall consumer prices are expected to rise 1.9% this year, according to economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal. RETAIL PRESSURES Still, the price increases pose a challenge for food makers, restaurants and retailers, which must decide how much of the costs they can pass along and still retain customers at a time of intense competition and thin profit margins. During previous inflationary periods, food makers switched to less-expensive ingredients or reduced package sizes to maintain their profit margins. Retailers and restaurants usually raise prices as a last resort.

One reason prices are higher now is the lingering effect from the historic 2012 U.S. drought, which sent animal-feed prices surging to record highs and caused livestock and dairy farmers to cull herds, analysts said. In California, the biggest U.S. producer of agricultural products, about 95% of the state is suffering from drought conditions, according to data from the U.S. Drought Monitor. This has led to water shortages that are hampering crop and livestock production. U.S. fresh-vegetable prices that jumped 4.7% last year are forecast to rise as much as 3% this year, while fruit that gained 2% last year will rise up to 3.5% in 2014, according to the USDA. Dry weather in Brazil has contributed to a dramatic increase this year in prices for arabica coffee, the world's most widely produced variety. Arabica-coffee futures, which were at a seven-year low last year, settled at a two-year high of $2.0505 a pound on March 13. In each of the past two years, global food prices on average declined from the previous year, as farmers ramped up production of wheat, sugar and other commodities, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, which publishes a monthly food-price index. But that index rose 5.2 points to 208.1 last month compared with January, the sharpest jump since mid-2012. EMERGING MARKETS Food-price increases are a particularly touchy issue for emerging markets, where spending on food accounts for a higher share of monthly budgets than in wealthier countries. In 2008, a spike in food prices caused riots from Haiti to sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Three years later, in 2011, rising food prices were a factor behind the Arab Spring protests in North Africa and the Middle East that ultimately toppled governments in Tunisia and Egypt. The increase in global prices last month surprised some economists, and raised the specter of more severe increases that could hit the world's poorest countries, economists said.

"To be honest, until a month ago, our feeling and thinking was that most markets were well-supplied," said John Baffes, a senior economist at the World Bank. "Now, the question is: Are those adverse weather conditions going to get worse? If they do, then indeed, we may see more food price increases. |

03-18-14 | GLOBAL RISK FOOD |

27 - Food Price Pressures | ||

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - March 16th - March 22nd, 2014 | |||||

| RISK REVERSAL | 1 | ||||

RISK - Reflexivity Suggests another Crash Is Inevitable Soros’s Reflexivity Suggests another Crash Is Inevitable 03-13-14 Chase Van Der Rhoer, Bloomberg Markets slumped on a toxic brew of headlines about the dismantling of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, writedowns from UniCredit, losses at Ceasars Entertainment and escalating tension between the West and the kremlin. Investment-grade corporates responded by widening 1 basis point with a 1:3 tightening to widening ratio, high yield widened 5 basis points with a 1:6 ratio and emerging markets widened 10 basis points with a 1:6 ratio. a market confronted with extreme complexity is obliged to resort to methods of simplification as George Soros points out in a paper entitled “Fallibility, Reflexivity, and the Human Uncertainty Principle.” He argues that interpreting the world, then acting upon that world, with both actions subject to great fallibility, creates a reflexive feedback loop that causes an escalat- ing probability of disaster. When the entanglement of flawed market expectations becomes large enough, Soros says, the market experiences a bust following predictable trends and stages. Echoing this analysis, stock analyst Tom Demark last year pointed to the similarity between the stock market trend that preceded the 1929 crash and the present day. The following two charts are examples of the boom-bust cycles overlaid with today’s equity market. |

03-17-14 | RISK CANARIIES | 1 - Risk Reversal | ||

RISK - Historically, Extended Bull Market Runs Ended Badly

|

03-17-14 | RISK CANARIIES | 1 - Risk Reversal | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 2 | ||||

| BOND BUBBLE | 3 | ||||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

4 |

||||

| SOVEREIGN DEBT CRISIS [Euope Crisis Tracker] | 5 | ||||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 6 | ||||

| TO TOP | |||||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||||

| Market | |||||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||||

PATTERNS - Beware When the Fed's Asset Quarterly (13 Wk) ROC Goes Negative FLOWS: Its the 2nd Derivative

|

03-17-14 | FLOWS | |||

| COMMODITY CORNER - HARD ASSETS | PORTFOLIO | ||||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||||

| THESIS | |||||

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|||

|

2013 2014 |

|||||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||||

| THEMES | |||||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | THEME | ||||

| SHADOW BANKING -LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | THEME | ||||

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | THEME | ||||

| ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | THEME | ||||

| PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX -NATURE OF WORK | THEME | ||||

| STANDARD OF LIVING -EMPLOYMENT CRISIS | THEME | ||||

| CORPORATOCRACY -CRONY CAPITALSIM | THEME |  |

|||

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE -MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|||

| SOCIAL UNREST -INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | THEME | ||||

| SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX -STATISM | THEME | ||||

| GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | THEME | ||||

| CENTRAL PLANINNG -SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER | THEME | ||||

| CATALYSTS -FEAR & GREED | THEME | ||||

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||||

| TO TOP | |||||

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP