|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

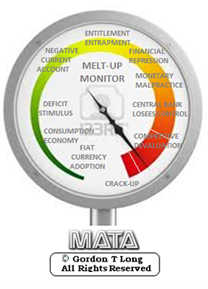

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Wed. Apr. 29th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS

2015 THESIS: FIDUCIARY FAILURE

2015 THESIS: FIDUCIARY FAILURE

NOW AVAILABLE FREE to Trial Subscribers

174 Pages

What Are Tipping Poinits?

Understanding Abstraction & Synthesis

Global-Macro in Images: Understanding the Conclusions

![]()

| APRIL | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

| 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | ||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

| 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

![]() Scroll TWEETS for LATEST Analysis

Scroll TWEETS for LATEST Analysis ![]()

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro |

|||

|

|

Posting Date |

Labels & Tags | TIPPING POINT or THEME / THESIS or INVESTMENT INSIGHT |

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

||

| STUDIES - MACRO pdf | |||

|

A Debt supercycle versus Secular Demand Stagnation Debt supercycle, not secular stagnation 04-22-15 VOX CEPR's Policy PortalKenneth RogoffWeak, post-Crisis growth has been blamed on secular stagnation. This column argues that the ‘financial crisis/debt supercycle’ view provides a more accurate and useful framework for understanding what has transpired and what is likely to come next. The difference matters. Unlike secular stagnation, a debt supercycle is not forever. After deleveraging and borrowing headwinds subside, expected growth trends might prove higher than simple extrapolations of recent performance might suggest. I want to address a narrow yet fundamental question for understanding the current challenges facing the global economy.1 Has the world sunk into ‘secular stagnation’, with a long future of much lower per capita income growth driven significantly by a chronic deficiency in global demand? Or does weak post-Crisis growth reflect the post-financial crisis phase of a debt supercycle where, after deleveraging and borrowing headwinds subside, expected growth trends might prove higher than simple extrapolations of recent performance might suggest (Lo and Rogoff 2015)? I will argue that the financial crisis/debt supercycle view provides a much more accurate and useful framework for understanding what has transpired and what is likely to come next. Recovery from financial crisis need not be symmetric; the UK and perhaps the UK have reached the end of the deleveraging cycle, while the Eurozone, due to weaknesses in its construction, is still very much in the thick of it. China, having markedly raised economy-wide debt levels in response to the crisis originating in the West, now faces its own challenges from high debt, particularly local government debt. The case for a debt supercycleThe evidence in favour of the debt supercycle view is not merely qualitative, but quantitative. The lead up to and aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis has unfolded like a garden variety post-WWII financial crisis, with very strong parallels to the baseline averages and medians that Carmen Reinhart and I document in our 2009 book, This Time is Different (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). The evidence is not simply the deep fall in output and subsequent very sluggish U-shaped recovery in per capita income that commonly characterise recovery from deep systemic financial crises. It also includes the magnitude of the housing boom and bust, the huge leverage that accompanied the bubble, the behaviour of equity prices before and after the Crisis, and certainly the fact that rises in unemployment were far more persistent than after an ordinary recession that is not accompanied by a systemic financial crisis. Even the dramatic rises in public debt that occurred after the Crisis are quite characteristic. Of course, the Crisis had unique features, most importantly the euro crisis that exacerbated and deepened the problem. Emerging markets initially recovered relatively quickly, in part because many entered the Crisis with relatively strong balance sheets. Unfortunately, a long period of higher borrowing by both the public sector and corporates has left emerging markets vulnerable to an echo of the advanced-country financial crisis, particularly as growth in China slows and the US Fed contemplates raising interest rates. Modern macroeconomics has been slow to get to grips with the of how to incorporate debt supercycles into canonical models, but there has been much progress in recent years (see Geanokoplos 2014 for a survey) and the broad contours help explain the now well-documented empirical regularities. As credit booms, asset prices rise, raising their value as collateral, thereby helping to expand credit and raise asset prices even more. When the bubble ultimately bursts, often catalysed by an underlying adverse shock to the real economy, the whole process spins into a harsh and precipitous reverse. Of course, policy played an important role. However, there has been far too much focus on orthodox policy responses and not enough on heterodox responses that might have been better suited to a crisis greatly amplified by financial market breakdown. In particular, policymakers should have more vigorously pursued debt write-downs (e.g. subprime debt in the US and periphery-country debt in Europe), accompanied by bank restructuring and recapitalisation. In addition, central banks were too rigid with their inflation target regimes. Had they been more aggressive in getting out in front of the Crisis by pushing for temporarily elevated rates, the problem of the zero lower bound might have been avoided. In general, failure to more seriously consider the kinds of heterodox responses that emerging markets have long employed is partly a reflection of an inadequate understanding of how advanced countries have dealt with banking and debt crises in the past (Reinhart et al. 2015). Fiscal policy (one of the instruments of the orthodox response) was initially very helpful in avoiding the worst of the Crisis, but then many countries tightened prematurely, as IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde rightly noted in her opening speech to the “Rethinking Macro Policy III” conference. Slowing the rate of debt accumulation was one motivation, as she notes, but let us not have collective amnesia. Overly optimistic forecasts played a central role in every aspect of most countries’ responses to the crisis. No one organisation was to blame, as virtually every major central bank, finance ministry, and international financial organisation was repeatedly overoptimistic. Most private and public forecasters anticipated that once a recovery began it would be V-shaped, even if somewhat delayed. In fact, the recovery took the form of the very slow U-shaped recovery predicted by scholars who had studied past financial crises and debt supercycles. The notion that the forecasting mistakes were mostly due to misunderstanding fiscal multipliers is thin indeed. The timing and strength of both the US and UK recoveries defied the predictions of polemicists who insisted that very slow and gradual normalisation of fiscal policy was inconsistent with recovery. Secular stagnationOf course, secular factors have played a role, as they always do in both good times and bad. Indeed, banking crises almost invariably have their roots in deeper real factors driving the economy, with the banking crisis typically being an amplification mechanism rather than a root cause. What are some particularly obvious secular factors? Well, of course, demographic decline has set in across most of the advanced world and is at the doorstep of many emerging markets, notably China. In the long run, global population stabilisation will be of huge help in achieving sustainable global economic growth, but the transition is surely having profound effects, even if we do not begin to understand all of them. Another less-trumpeted secular factor is the inevitable tapering off of rising female participation in the labour force. For the past few decades, the ever greater share of women in the labour force has added to measured per capita output, but the main shift is likely nearing an end in many countries, and as such will no longer contribute to growth. Then there is also the supercycle of Asia’s rise in the global economy, particularly China. Asian growth has been pushing up IMF estimates of global potential growth for three decades now. As China shifts to a more consumption-based domestic-demand-driven growth model, its growth will surely taper off, with significant effects around the globe on consumers’ real incomes and on commodity prices, among other factors. As Asian growth slows, global growth will likely tend back towards its 50 year average. Going forward, perhaps the most difficult secular factor to predict is technology. Technology is the ultimate driver of per capita income growth in the classic Solow growth model. Some would argue that technology is stagnating, with computers and the internet being a relatively modest and circumscribed advance compared to past industrial revolutions. Perhaps, but there are reasons to be much more optimistic. Economic globalisation, communication and computing trends all suggest an environment highly conducive to continuing rapid innovation and implementation, not a slowdown. Indeed, I personally am far more worried that technological progress will outstrip our ability to socially and politically adapt to it, rather than being worried that innovation is stagnating. Of course, given tight credit in the aftermath of the financial crisis, some technologies may have been ‘trapped’ by lack of funding. But the ideas are not lost and the cost to growth is not necessarily permanent. What of Solow’s famous 1987 remark that “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the statistics”? Perhaps, but one has to wonder to what extent the statistics accurately capture the welfare gains embodied in new goods during a period of such rapid technological advancement. Examples abound. In advanced countries, the possibilities for entertainment have expanded exponentially, with consumers having at their fingertips a treasure-trove of music, films and TV that would have been unimaginable 25 years ago. Quality-of-health improvements through the low-cost use of statins, ibuprofen and other miracle drugs are widespread. It is easy to be cynical about social media, but the fact is that humans enormously value connectively, even if GDP statistics really cannot measure the consumer surplus from these inventions. Skype and other telephony advances allow a grandmother to speak with a grandchild face to face in a distant city or country. Disruptive technologies such as Uber point the way towards vastly more efficient uses of the existing capital stock. Yes, there are negative trends such as environmental degradation that detract from welfare, but overall it is quite likely that measured GDP growth understates actual growth, especially when measured over long periods. It is quite possible that future economic historians, using perhaps more sophisticated measurement techniques, will evaluate ours as an era of strong growth in middle-class consumption, in contradiction to the often polemic discussion one sees in public debate on the issue. All in all, the debt supercycle and secular stagnation view of today’s global economy may be two different views of the same phenomenon, but they are not equal. The debt supercycle model matches up with a couple of hundred years of experience of similar financial crises. The secular stagnation view does not capture the heart attack the global economy experienced; slow-moving demographics do not explain sharp housing price bubbles and collapses. Low real interest rates mask an elevated credit surfaceWhat about the very low value of real interest rates? Low rates are often taken as prima facie by secular stagnation proponents, who argue that only a chronic demand deficiency could be responsible for steadily driving down the global real interest rate. The steady decline of real interest rates is certainly a puzzle, but there are a host of factors. First, we do not actually observe the true economic real interest rate; that would require a utility-based price index that is extremely difficult to construct in a world of rapid change in both the kinds of goods we consume and the way we consume them. My guess is that the true real interest rate is higher, and perhaps this bias is larger than usual. Correspondingly, true economic inflation is probably considerably lower than even the low measured values that central banks are struggling to raise. Perhaps more importantly, in a world where regulation has sharply curtailed access for many smaller and riskier borrowers, low sovereign bond yields do not necessarily capture the broader ‘credit surface’ the global economy faces (Geanokoplos 2014). Whether by accident or design, banking and financial market regulation has hugely favoured low-risk borrowers (governments and cash-heavy corporates), knocking out other potential borrowers who might have competed up rates. Many of those who can borrow face higher collateral requirements. The elevated credit surface is partly due to inherent riskiness and slow growth in the post-Crisis economy, but policy has also played a large role. Many governments, particularly in Europe, have rammed down the throats of pension funds, banks, and insurance companies. Financial repression of this type not only effectively taxes middle-income savers and pensioners (who receive low rates of return on their savings) but also potential borrowers (especially middle-class consumers and small businesses), which these institutions might have financed to a greater extent if they were not required to be so overweight in government debt. Surely global interest rates are also affected by the massive balance sheet expansions that most advanced-country central banks have engaged in. I don’t believe this is as important as the other effects I have discussed (even if most market participants would say the reverse). Global quantitative easing by advanced countries and sterilised intervention operations by emerging markets have also surely had a very large impact on bringing down market volatility measures. The fact that global stock market indices have hit new peaks is certainly a problem for the secular stagnation theory, unless one believes that profit shares are going to rise massively further. I won’t pretend there is one simple explanation for the stock-bond disconnect (after all, I have already listed several). But one important observation follows the work of my colleague Robert Barro. He has shown that in canonical equilibrium macroeconomic models (could be Keynesian, but his is not), small changes in the market perception of tail risks can lead both to significantly lower real risk-free interest rates and a higher equity premium. Another one of my colleagues, Martin Weitzman, has espoused a different variant of the same idea based on how people form Bayesian assessments of the risk of extreme events. Indeed, it is not hard to believe that the average global investor changed their general assessment of all types of tail risks after the global financial crisis. The fact that emerging market investors are playing a steadily increasing role in global portfolios also plausibly raises generalised risk perceptions, since of course many of these investors inhabit regions that are still inherently riskier than advanced countries. I don’t have time to go into great detail here, though I have discussed the idea for many years in policy writings (Rogoff 2015), and have explored the idea analytically in a recent paper with Carmen and Vincent Reinhart (Reinhart et al. 2015). Of course, a rise in tail risks will also initially cause asset prices to drop (as they did in the financial crisis), but then subsequently they will offer a higher rate of return to compensate for risk. All in all, a rise in tail risks seems quite plausible, even if massive central bank intervention sometimes masks the effect in market volatility measures. What are the policy differences between the debt supercycle and secular stagnation view?When it comes to government spending that productively and efficiently enhances future growth, the differences are not first order. With low real interest rates, and large numbers of unemployed (or underemployed) construction workers, good infrastructure projects should offer a much higher rate of return than usual. However, those who would argue that even a very mediocre project is worth doing when interest rates are low have a much tougher case to make. It is highly superficial and dangerous to argue that debt is basically free. To the extent that low interest rates result from fear of tail risks a la Barro-Weitzman, one has to assume that the government is not itself exposed to the kinds of risks the market is worried about, especially if overall economy-wide debt and pension obligations are near or at historic highs already. Obstfeld (2013) has argued cogently that governments in countries with large financial sectors need to have an ample cushion, as otherwise government borrowing might become very expensive in precisely the states of nature where the private sector has problems. Alternatively, if one views low interest rates as giving a false view of the broader credit surface (as Geanokoplos argues), one has to worry whether higher government debt will perpetuate the political economy of policies that are helping the government finance debt, but making it more difficult for small businesses and the middle class to obtain credit. Unlike secular stagnation, the debt supercycle is not forever. As the economy recovers, the economy will be in position for a new rising phase of the leverage cycle. Over time, financial innovation will bypass some of the more onerous regulations. If so, real interest rates will rise though the overall credit surface facing the economy will flatten and ease. Sundry unrelated issuesLet me conclude by briefly touching on a few further issues. First, it is unfortunate that in the debate over the size of government, there is far too little discussion of how to make government a more effective provider of services. The case for having a bigger government can be strengthened when combined with ways of finding out how to make government better. Education would seem to be a leading example. Second, inequality within advanced countries is certainly a problem and plausibly plays a role in the global shift to a higher savings rate. Tax policy should be used to address these secular trends, perhaps starting with higher taxes on urban land, which seems to lie at the root of inequality in wealth trends. I am puzzled again, however, that those who claim to be interested in inequality from a fairness perspective pay so much attention to the world’s upper middle class (the middle class of advanced countries), and so little attention to the true global middle class. Shouldn’t a factory worker in China should get the same weight in global welfare as one in France? If so, the past 30 years have largely been characterised by historic decreases in inequality (Rogoff 2014), not rises as many seem to believe. In any event, these are all important issues, but should not be confused with longer-term output per capita trends. Concluding remarksIn sum, the case for describing the world as being in a debt supercycle is both theoretically and empirically compelling. The case for secular stagnation is far thinner. It is always very difficult to predict long-run future growth trends, and although there are some headwinds, technological progress seems at least as likely to outperform over the next two decades as it is to exhibit a sharp slowdown. Again, the US appears to be near the tail end of its leverage cycle, Europe is still deleveraging, while China may be nearing the downside of a leverage cycle. Though many factors are at work, the view that we have lived through a debt supercycle, marked by a severe financial crisis (Lo and Rogoff 2015), is far more constructive for policy analysis than the view that the world is suffering from long-term secular stagnation due to a chronic shortfall of demand. ReferencesGeanakoplos, J (2014), “Leverage, Default, and Forgiveness: Lessons from the American and European Crises”, Journal of Macroeconomics 39, pp. 313-222. Lo, S and K Rogoff (2015), “Secular stagnation, debt overhang and other rationales for sluggish growth, six years on”, BIS Working Paper No. 482. Obstfeld, M (2013), “On Keeping Your Powder Dry: Fiscal Foundations of Financial and Price Stability", CEPR DP No. 9563. Reinhart, C and K Rogoff (2009), This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. Reinhart, C, V Reinhart and K Rogoff (2015), “Dealing with Debt”, Journal of International Economics, forthcoming. Rogoff, K (2014), “Where is the Inequality Problem?”, Project Syndicate, 8 May. Rogoff, K (2015), “The Stock-Bond Disconnect”, Project Syndicate, 9 March. [] Endnotes[1] This column is based on the author’s Background Notes for Remarks at Closing Panel, “Rethinking Macro Policy III,” IMF, Washington DC, 16 April 2015. |

04-29-15 | STUDY | |

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - April 26th, 2015 - May. 2nd, 2015 | |||

| BOND BUBBLE | 1 | ||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 2 | ||

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | 3 | ||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 4 | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 5 | ||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

6 |

||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

JOHN BROWNE is the Senior Market Strategist for Euro Pacific Capital, Inc. Mr. Brown is a distinguished former member of Britain's Parliament who served on the Treasury Select Committee, as Chairman of the Conservative Small Business Committee, and as a close associate of then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Among his many notable assignments, John served as a principal advisor to Mrs. Thatcher's government on issues related to the Soviet Union, and was the first to convince Thatcher of the growing stature of then Agriculture Minister Mikhail Gorbachev. As a partial result of Brown's advocacy, Thatcher famously pronounced that Gorbachev was a man the West "could do business with." A graduate of the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Britain's version of West Point and retired British army major, John served as a pilot, parachutist, and communications specialist in the elite Grenadiers of the Royal Guard. In addition to careers in British politics and the military, John has a significant background, spanning some 37 years, in finance and business. After graduating from the Harvard Business School, John joined the New York firm of Morgan Stanley & Co as an investment banker. He has also worked with such firms as Barclays Bank and Citigroup. During his career he has served on the boards of numerous banks and international corporations, with a special interest in venture capital. He is a frequent guest on CNBC's Kudlow & Co. and a former contributing editor and columnist of NewsMax Media's Financial Intelligence Report and Moneynews.com. He holds FINRA series 7 & 63 licenses. OPEN ACCESS JOHN BROWNE TALKS FINANCIAL REPRESSION Published 04-27-15

40 Minutes FINANCIAL REPRESSION "It is the financial repression of the ordinary individual in America. It is happenig through three main avenues or arteries.

"I don't believe the central bank is necessarily evil, just unbelievably Irresponsible! LIQUIDITY TRAP "I think we are now seeing a situation which you could call a liquidity trap. There is so much money around that if they start to raise interest rates they are going to discourage people even more from spending. Ordinary individuals have low wages (wages have been flat for six years at least) yet taxes are going up (the number of taxes) as well as charges (licenses and fees)" "They are pushing on a string. It isn't liquidity that matters but wages and income!" "How does the Fed create income without just giving us cash in the post (mail) by just sending us checks? BY DESIGN "I'm afraid I believe at the very top it is devious! If I connect all the dots together I cannot feel it is by accident - it by design. I think the president wants to distribute American wealth around America, but even worse is to distribute American wealth around the world. Its kiling the economy and its kiliing America." "It means (eventually) everyone is going to look towards the government for solutions - that is when totalitarian governments come in (to existence)" "The only solution is single term politicians - Turkey's don't vote for an early Thanksgiving!" "

|

|||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

|||

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | G | THEME | |

| - - CORPORATOCRACY - CRONY CAPITALSIM | THEME |  |

|

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | |

II-ECONOMIC |

|||

| GLOBAL RISK | |||

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | |

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | |||

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

|

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

III-FINANCIAL |

|||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | THEME | ||

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | |

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

| TO TOP | |||

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP