|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

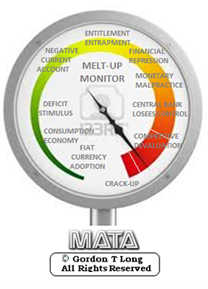

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Thurs. Sept 24th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

onTWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

ANNUAL THESIS PAPERS

FREE (With Password)

THESIS 2010-Extended & Pretend

THESIS 2011-Currency Wars

THESIS 2012-Financial Repression

THESIS 2013-Statism

THESIS 2014-Globalization Trap

THESIS 2015-Fiduciary Failure

NEWS DEVELOPMENT UPDATES:

FINANCIAL REPRESSION

FIDUCIARY FAILURE

WHAT WE ARE RESEARCHING

2015 THEMES

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY

PENSION POVERITY

WAR ON CASH

ECHO BOOM

PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX

FLOWS - LIQUIDITY, CREDIT & DEBT

GLOBAL GOVERNANCE

- COMING NWO

WHAT WE ARE WATCHING

(A) Active, (C) Closed

MATA

Q3 '15- Chinese Market Crash

(A)

Q3 '15-

GMTP

Q3 '15- Greek Negotiations

(A)

Q3 '15- Puerto Rico Bond Default

MMC

OUR STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS (SII)

NEGATIVE-US RETAIL

NEGATIVE-ENERGY SECTOR

NEGATIVE-YEN

NEGATIVE-EURYEN

NEGATIVE-MONOLINES

POSITIVE-US DOLLAR

ARCHIVES

| SEPTEMBER | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

| 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

Reading the right books?

No Time?We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

|

|||

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

||

GLOBAL GROWTH |

8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

||

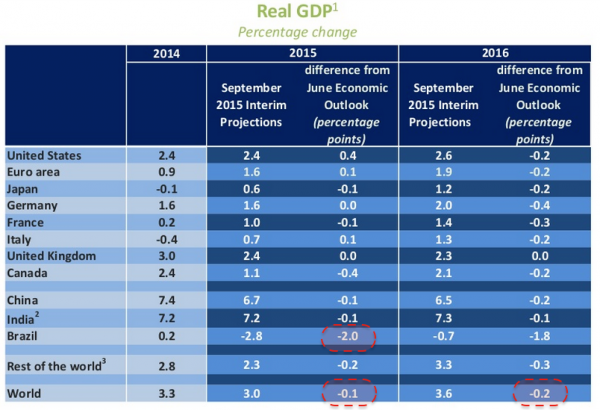

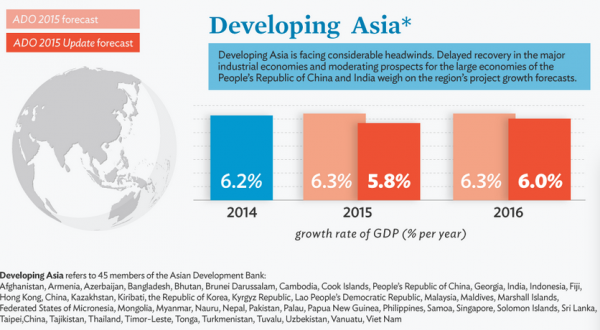

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 09/22/2015 22:13 ADB Joins OECD, WTO In Dismal Assessment Of Global GrowthExactly a week ago, we highlighted a WSJ piece which quoted WTO chief economist Robert Koopman as saying the following about the outlook for global growth: “We have seen this burst of globalization, and now we’re at a point of consolidation, maybe retrenchment. It’s almost like the timing belt on the global growth engine is a bit off or the cylinders are not firing as they should.” Explaining further, The Journal noted that “for the third year in a row, the rate of growth in global trade is set to trail the already sluggish expansion of the world economy.” In no uncertain terms: global growth and trade are grinding to a halt, something we’ve been keen to drive home this year using a variety of data points not the least of which are freight rates which, as Goldman noted back in May are likely to remain depressed until 2020, dead cat bounces in the Baltic Dry notwithstanding (for more on this, see here). All of the above was confirmed last Wednesday by the OECD which cut their forecast for global growth to 3% in 2015 and 3.6% in 2016. Of course one of the main problems is decreased demand from China, where sharply decelerating economic growth threatens to plunge the entire emerging world into crisis as the country’s previously insatiable appetite for raw materials suddenly disappeared leaving countries like Brazil out in the cold. Also hard hit is emerging Asia, where the turmoil in China combined with the threat of an imminent Fed hike has created conditions that may ultimately usher in the return of the 1997/98 Asian Currency Crisis (indeed, Malaysia’s central bank governor Zeti Akhtar Aziz has been at pains to reassure the market that the country isn’t set to return to capital controls to shore up the plunging ringgit). Against this backdrop it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the ADB slashed its growth outlook for the region on Tuesday citing a laundry list of factors, most of which are outlined above. Here’s more:

As that pretty much speaks for itself, we'll close with what we said last week in the wake of the OECD's most recent report:

|

|||

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK -Sept 20th, 2015 - Sept. 26th, 2015 | |||

| BOND BUBBLE | 1 | ||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 2 | ||

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | 3 | ||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 4 | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 5 | ||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

6 |

||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

|||

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | THEME | ||

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | |

II-ECONOMIC |

|||

| GLOBAL RISK | |||

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | |

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | |||

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

|

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

III-FINANCIAL |

|||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | THEME | ||

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | |

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

| TO TOP | |||

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP