|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

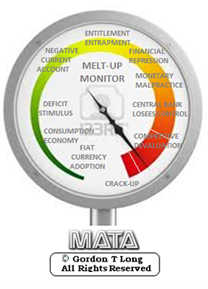

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

Weekend July 4th, 2015

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

![]()

| JUNE | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| 20 - US Dollar Weakness |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

| 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

TODAY'S TIPPING POINTS

|

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

|

|||

TIPPING POINTS |

|||

| SII | |||

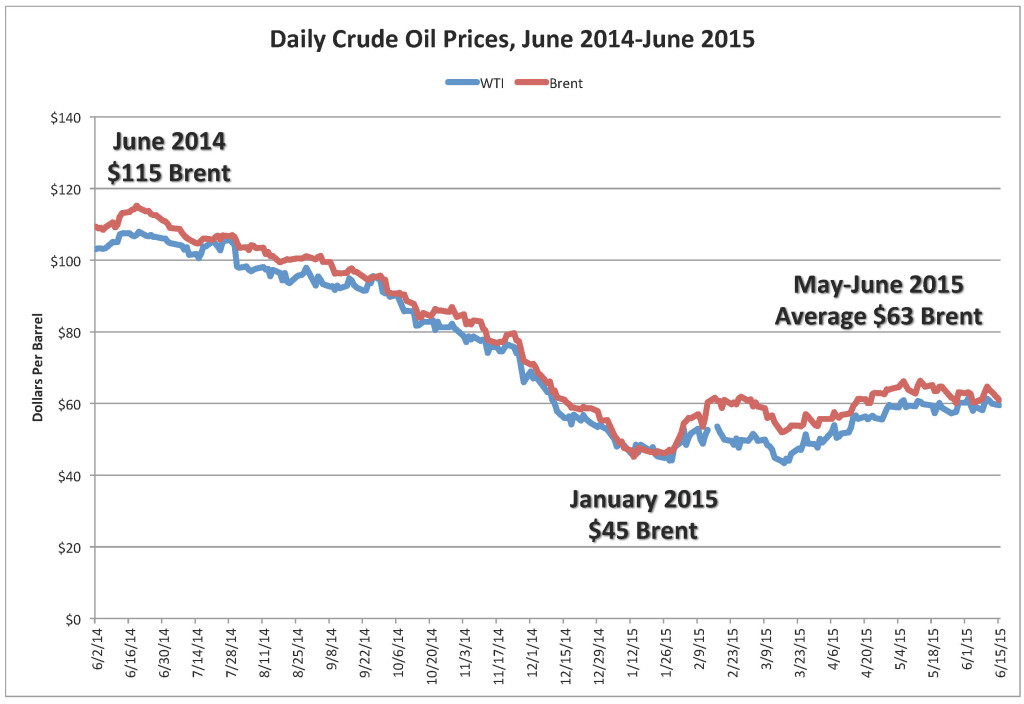

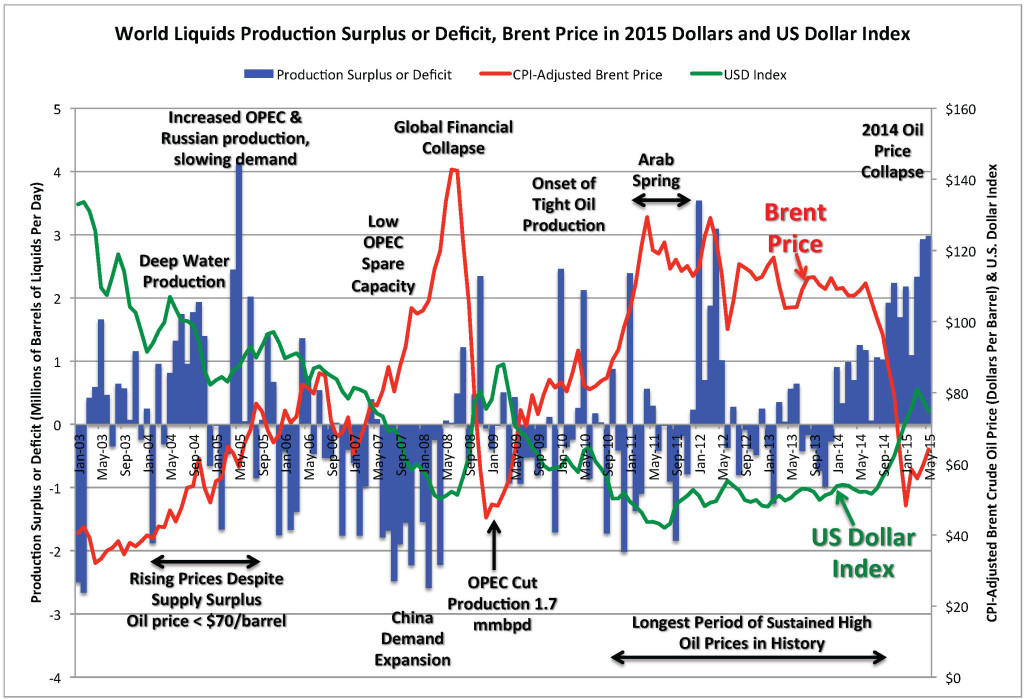

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 07/01/2015 19:30 -0400 The Current Oil Price Slump Is Far From OverThe oil price collapse of 2014-2015 began one year ago this month (Figure 1). The world crossed a boundary in which prices are not only lower now but will probably remain lower for some time. It represents a phase change like when water turns into ice: the composition is the same as before but the physical state and governing laws are different.*

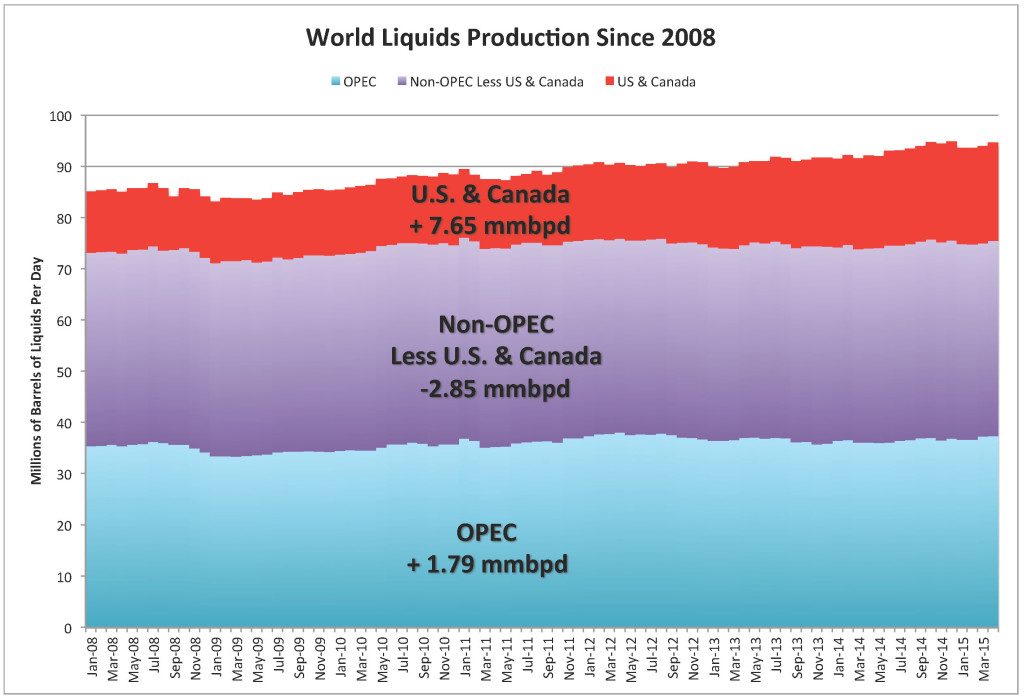

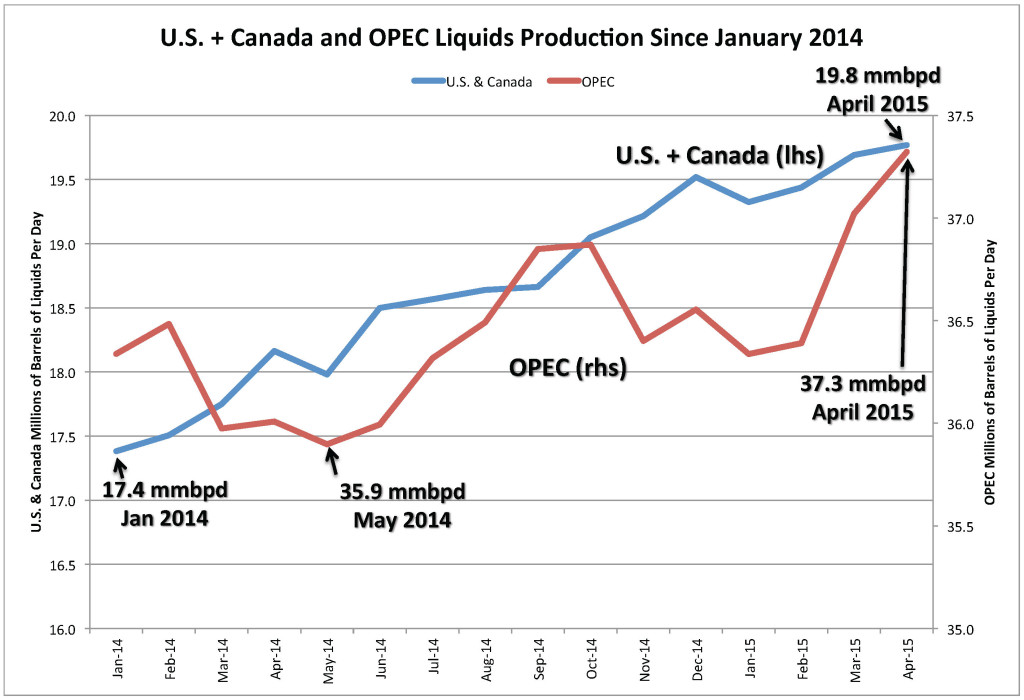

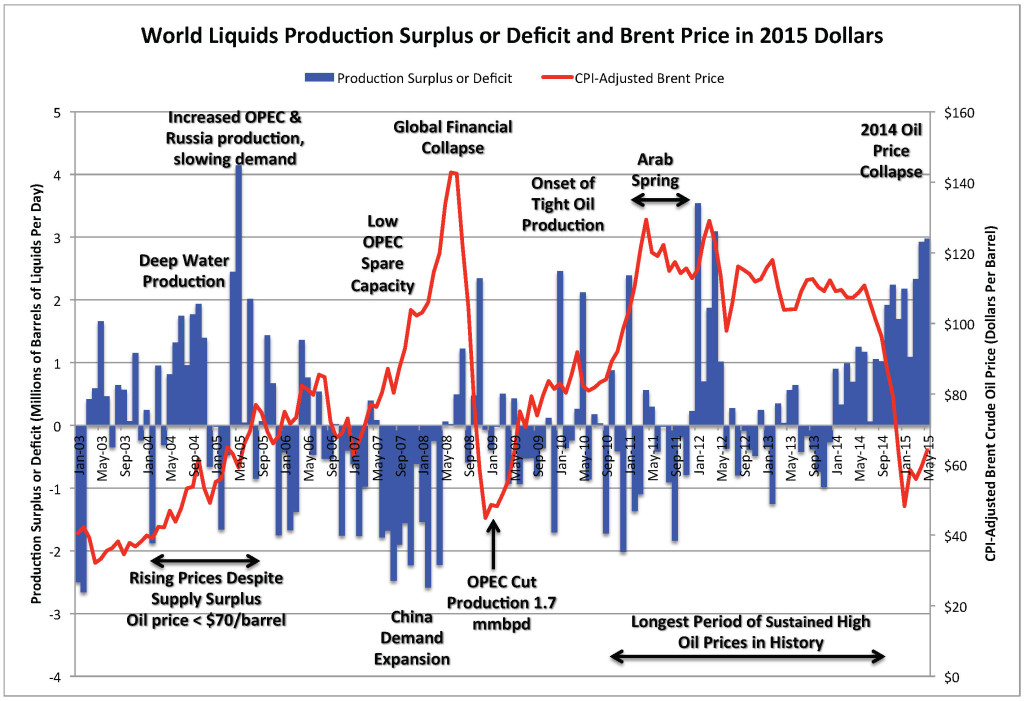

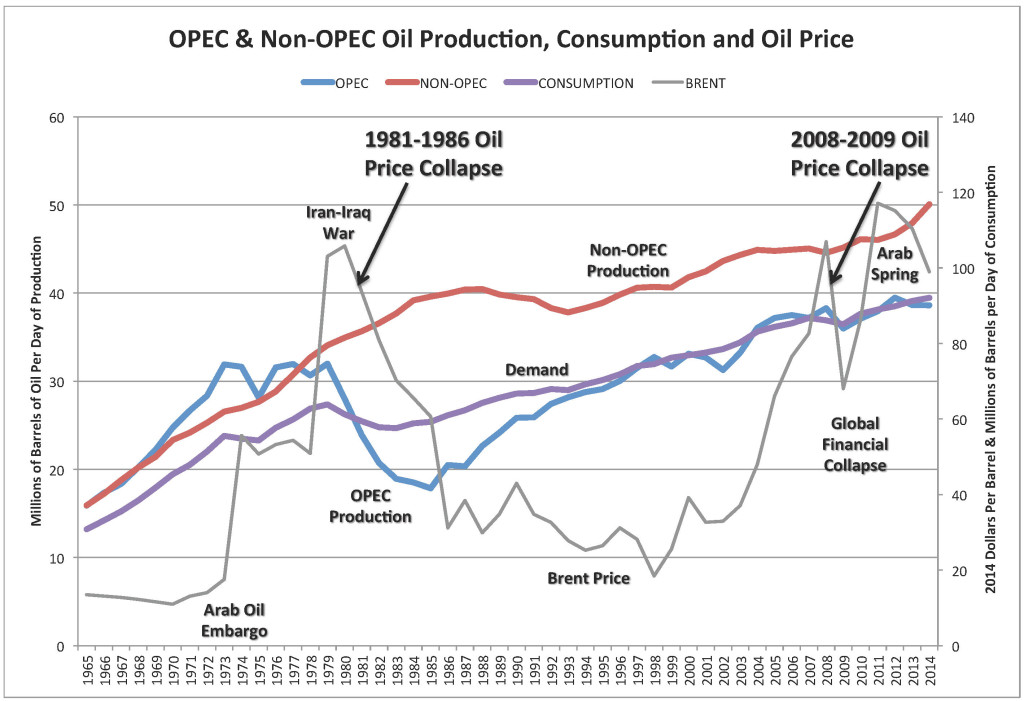

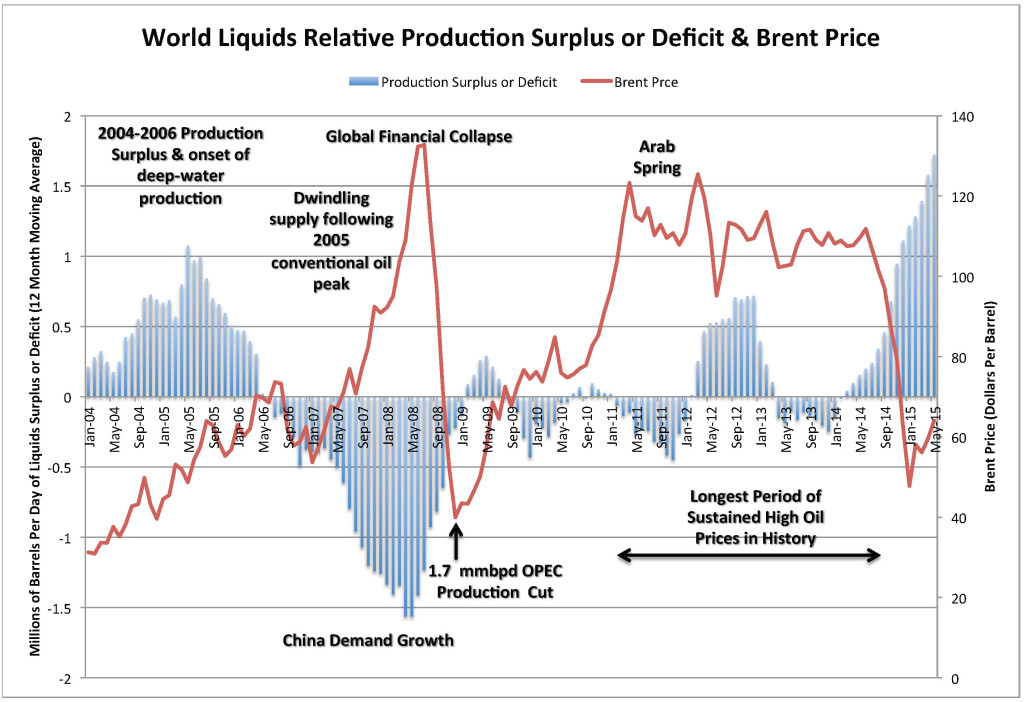

For oil prices, the phase change was caused mostly by the growth of a new source of supply from unconventional, expensive oil. Expensive oil made sense only because of the longest period ever of high oil prices in real dollars from late 2010 until mid-2014. The phase change occurred also because of a profoundly weakened global economy and lower demand growth for oil. This followed the 2008 Financial Collapse and the preceding decades of reliance on debt to create economic expansion in a world approaching the limits of growth. If the cause of the Financial Collapse was too much debt, the solution taken by central banks was more debt. This may have saved the world from an even worse crisis in 2008-2009 but it did not result in growing demand for oil and other commodities necessary for an expanding economy. Monetary policies following the 2008 Collapse produced the longest period of sustained low interest rates in recent history. As a result, capital flowed into the development and over-production of marginally profitable unconventional oil because of high coupon yields compared with other investments. The devaluation of the U.S. dollar following the 2008 Financial Collapse corresponded to a weak currency exchange rate and an increase in oil prices. The fall in oil prices in mid-2014 coincided with monetary policies that strengthened the dollar. Prolonged high oil prices caused demand destruction. This also allowed the expansion of renewable energy that could compete only at high energy costs. Concerns about global climate change and its relationship to burning oil and other fossil energy threatened the future interests of conventional oil-exporting countries. OPEC hopes to regain market share from expensive unconventional oil and renewable energy, and to renew demand for oil through several years of low oil prices. OPEC increased production in mid-2014, and decided not to cut production at its November 2014 meeting By January 2015 oil prices fell below $50 per barrel. Most observers expected a sharp reduction in U.S. tight oil production after rig counts fell with lower prices. Production fell in early 2015 but recovered as new capital poured into North American E&P companies. This and the partial recovery of oil prices into the mid-$60 per barrel range gave expensive oil another day to survive and fight. If capital continues to flow to unconventional oil companies and OPEC’s resolve stays firm, oil prices could average near the present range for many years. Oil prices will probably fall in the second half of 2015 as the ongoing production surplus and weak demand overcome the sentiment-based belief that a price recovery is already underway. Oil prices must inevitably rise as unconventional production peaks over the next decade and oil-exporting countries increasingly consume more of their own oil. Politically driven supply interruptions will inevitably punctuate the emerging new reality with periods of higher prices. For now, however, we have crossed a boundary and notions of normal or business-as-usual should be put aside. A New Supply Source and Over-Production The main cause of the price collapse of 2014-2015 was over-production of oil. Most of the increase came from unconventional production in the United States and Canada–tight oil, oil sands and deep-water oil. From 2008 to 2015, U.S. and Canadian production increased 7.65 million barrels per day (mmpbd). During the same period, non-OPEC production less the U.S. and Canada decreased 2.85 mmbpd and OPEC production increased 1.79 mmbpd (Figure 2).

North American unconventional and OPEC conventional production increased almost 4 mmbpd in 2014 alone (Figure 3).

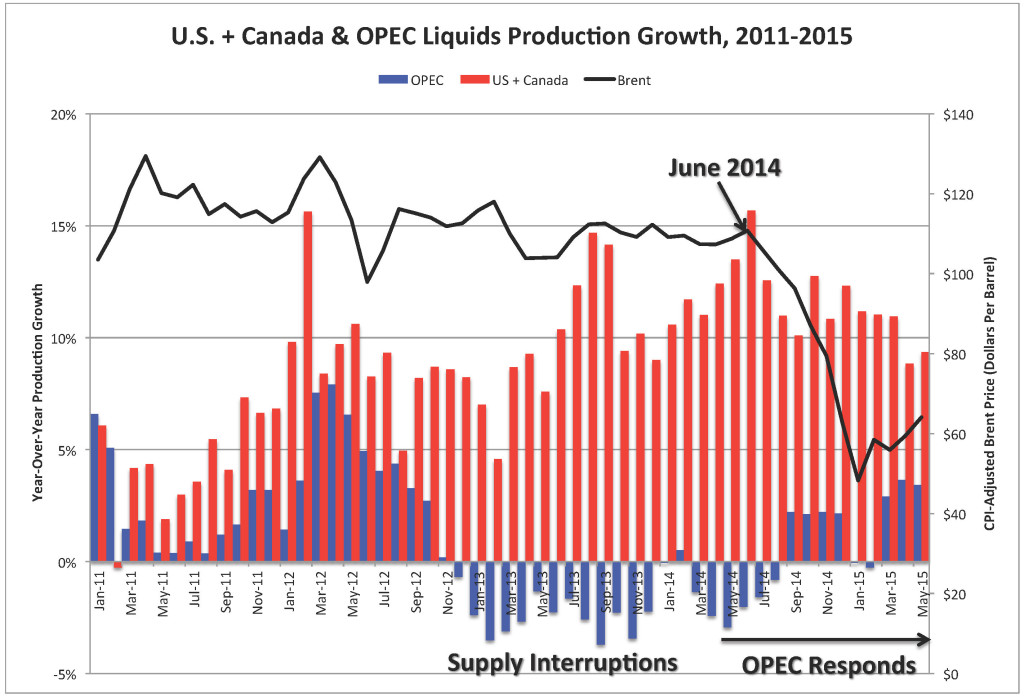

Through 2013, unconventional production growth was matched by decreases in OPEC production mostly from supply interruptions due to political events (Figure 4). The result was that prices remained high despite increases in unconventional production.

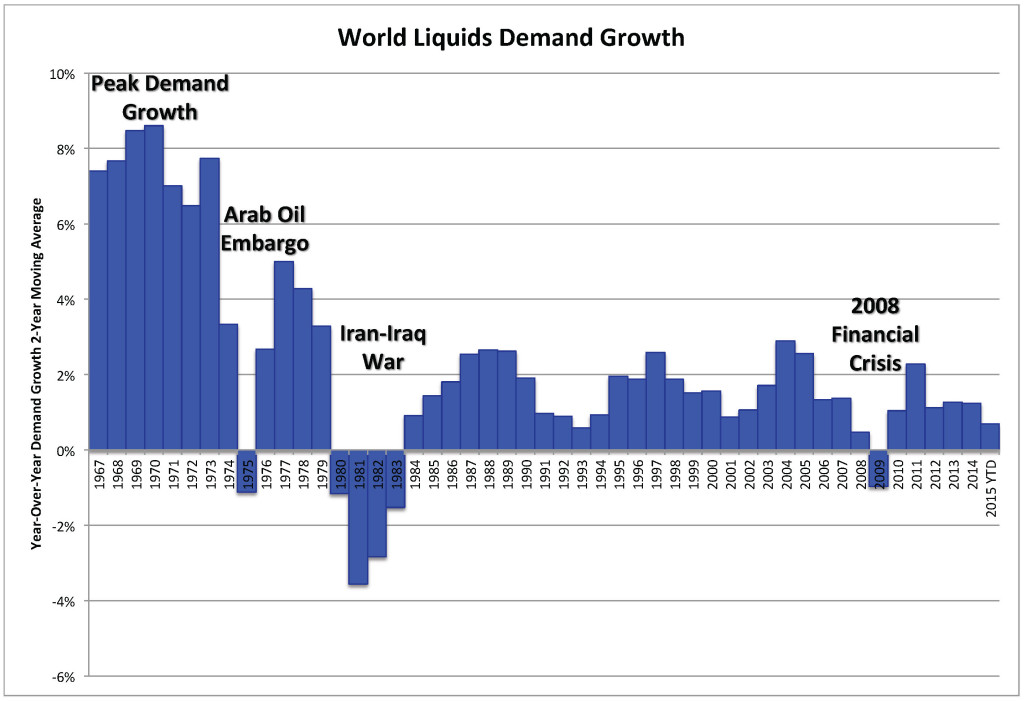

OPEC responded to defend its market share in mid-2014 by increasing production. Prices started falling in late June 2014 from $115 per barrel (Brent) and reached a low in late January 2015 of $47 per barrel after OPEC decided not to cut production at its November 2014 meeting. Unconventional production slowed and fell in early 2015. Then, prices increased beginning in February and Brent has averaged $63 per barrel since May 1 (WTI average $59 per barrel). Over-production continues as different parties struggle for market share, for cash flow to survive, or both. If high oil prices created the conditions for unconventional oil to grow and challenge OPEC’s market share, then prolonged low oil prices must be part of OPEC’s solution. By keeping prices below the marginal cost of unconventional production (about $75 per barrel), OPEC hopes that expensive oil production will decline along with the fortunes of the companies engaged in these plays. Decreased Demand and Demand Destruction OPEC is as concerned about long-term demand as it is about market share. Oil is the only major source of revenue for many OPEC countries and low demand, potential competition from other fuel sources, and the effect of a perceived link between oil use and climate change are existential threats. Demand growth for oil has been declining since the late 1960s (Figure 5). OPEC hopes to stimulate demand through low oil prices back to the peak levels that existed before the price shocks of the 1970s and 1980s.

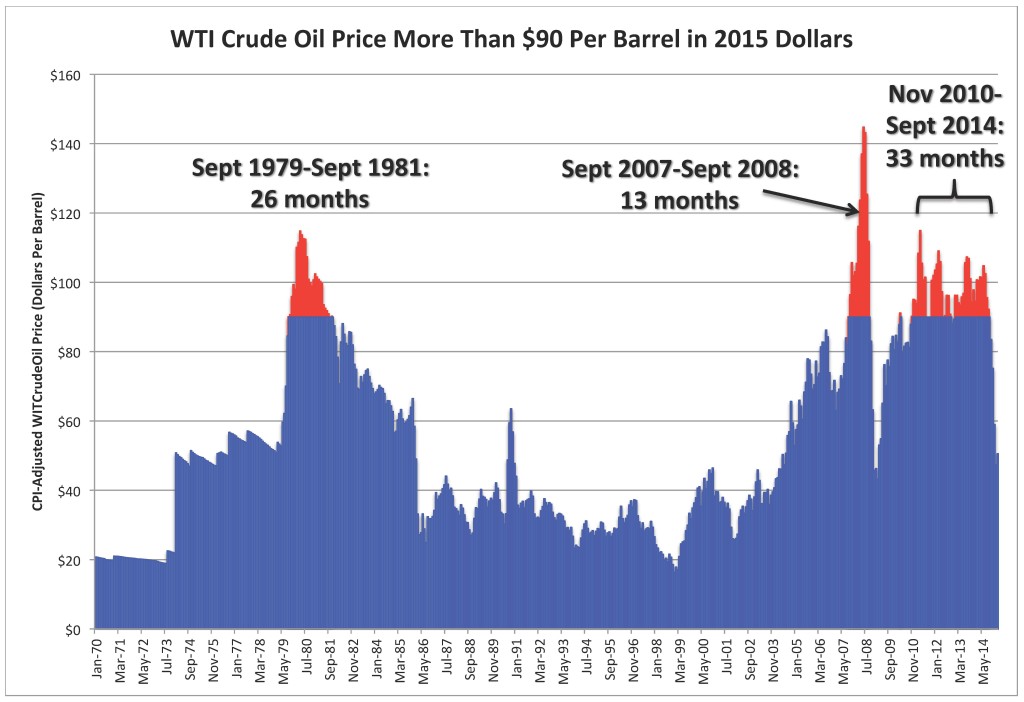

Demand destruction followed periods of high oil prices from 1979-1981 (Iran-Iraq War) and from 2007-2008 (demand growth from China). 2010-2014 was the longest period in history–33 months–of oil prices above $90 per barrel in real dollars (Figure 6). Since 2011, demand growth has fallen to only 0.5% per year so far in 2015 (Figure 5).

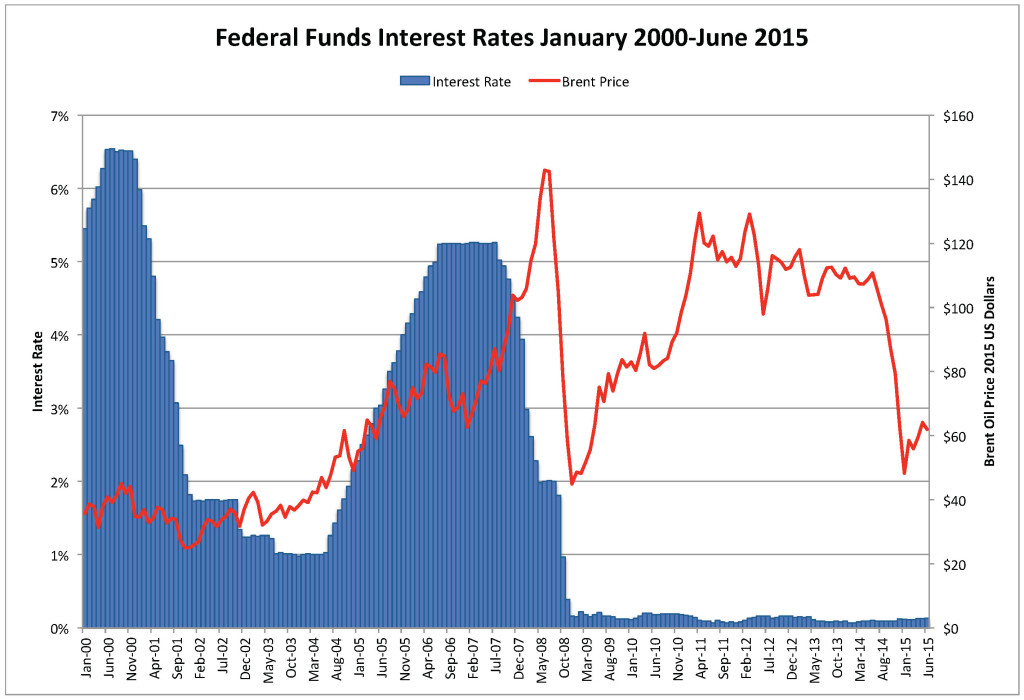

Prolonged low oil prices may restore growth to the global economy accomplishing what the central banks have failed to do since 2008. If successful, interest rates should rise and this may restrict the flow of capital to unconventional E&P companies. Most of the capital provided to these companies comes from high-yield (“junk”) corporate bond sales, preferred share offerings, and debt. In a zero-interest rate world (Figure 7), these provide yields that are are much higher than those found in more conventional investments like U.S. Treasury bonds or money market accounts. If interest rates increase with a stronger economy, capital may flow to more productive investments that offer yields that are more competitive with higher risk tight oil offerings.

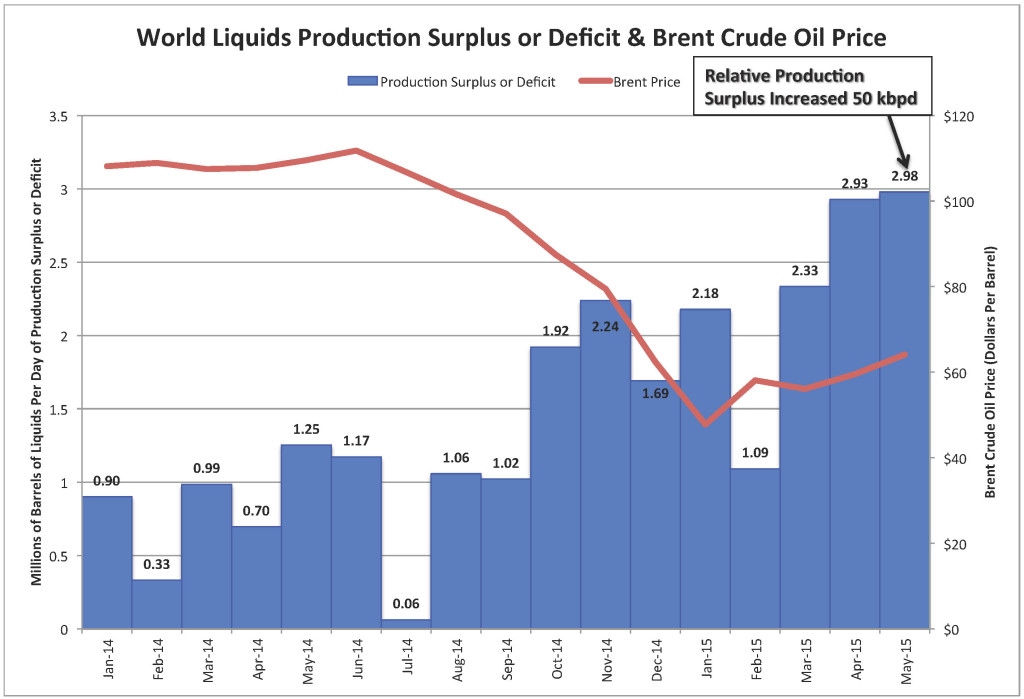

Over-Production Continues The over-production that began the oil price collapse continues and has gotten worse. The global production surplus (production minus consumption) has gone on for 17 months and has grown from 1.25 mmbpd in May 2014, just before prices began to fall, to almost 3 mmbpd in May 2015 (Figure 8).

We may take some comfort that the rate of increase has slowed but it is difficult to explain the increase in prices over the last few months based on supply and demand. The production supply surplus that is largely responsible for the current oil-price collapse is not a trivial event that will likely go away soon unless production is cut either by unconventional producers or OPEC. Earlier production surpluses in May 2005 and January 2012 were higher than today but were short-lived and related to specific non-systemic factors (Figure 9).

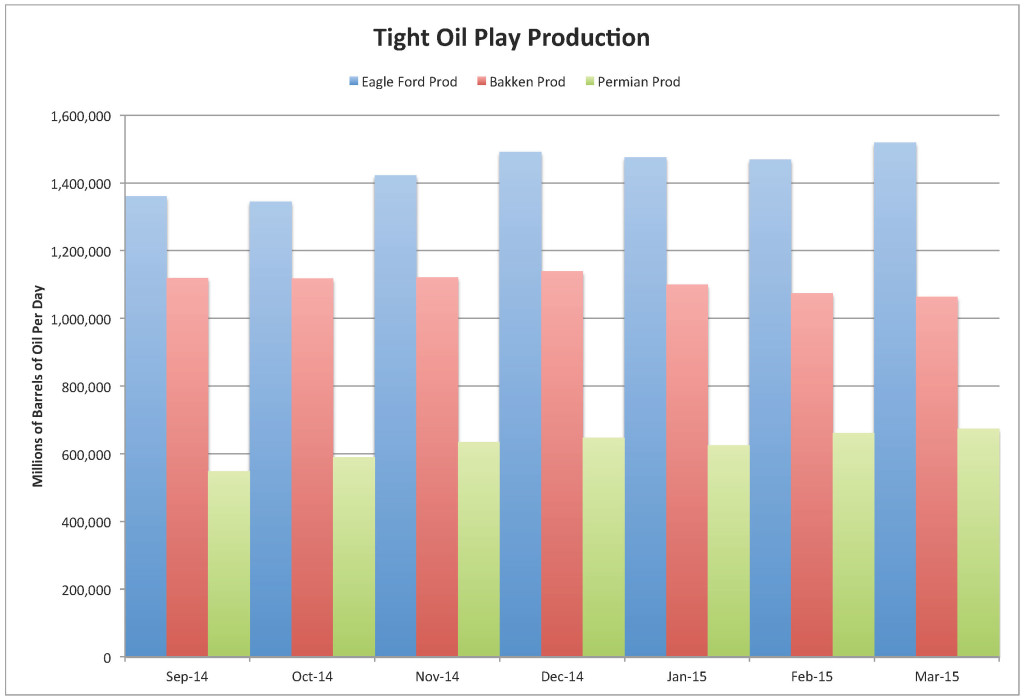

The present supply imbalance is structural and persistent. The only comparable episode in recent history was the production deficit immediately before the 2008 Financial Collapse that lasted 11 months. It was driven by growing Chinese and other Far East demand and by dwindling oil supplies following the peak of conventional production in 2005. For now, OPEC appears committed to continued over-production to achieve its goals. Its production increased 1.4 million barrels of liquids per day during the last year (Figure 3) and some analysts suggest it might increase by an equal amount again in coming months. Meanwhile, U.S. production has not fallen much so far. Production from the main tight oil plays fell about 77,000 bpd in January 2015, was basically flat in February and increased 51,000 bpd in March (Figure 10). This is partly because companies are high-grading well completions in the best parts of the plays. It is also because of the backlog of drilled but uncompleted wells that are being brought on production at a fraction of the incremental cost of drilling new wells.

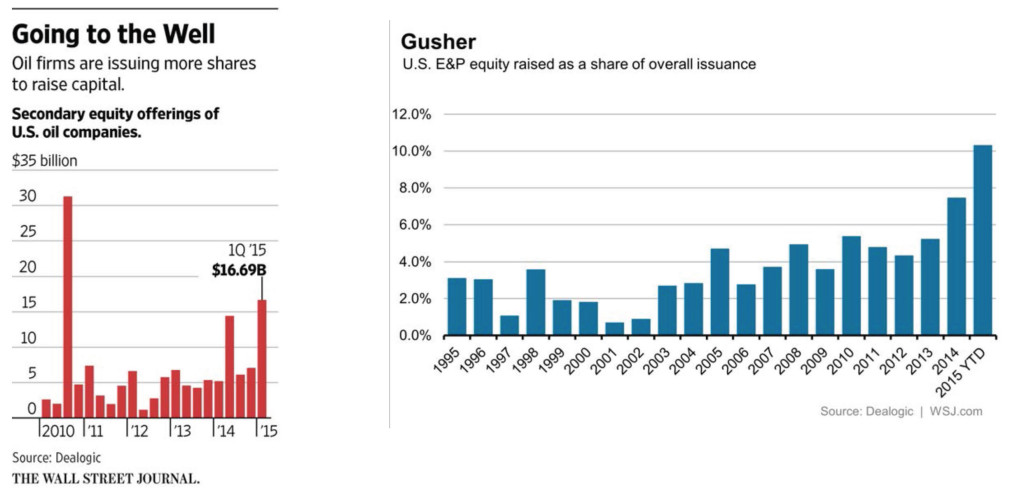

But the most significant factor is that capital flow to U.S. unconventional plays has increased. Figure 11 shows that almost $17 billion in equity offerings flowed to U.S. oil companies in the first quarter of 2015, more than in any other period since 2010. The percent of E&P equity rose to over 10% of overall issuance from an average of about 4-5% over the last decade. This can only be explained because there are no alternative investments with comparable yields and that investors believe that they are buying assets that are somehow viable at current oil prices.

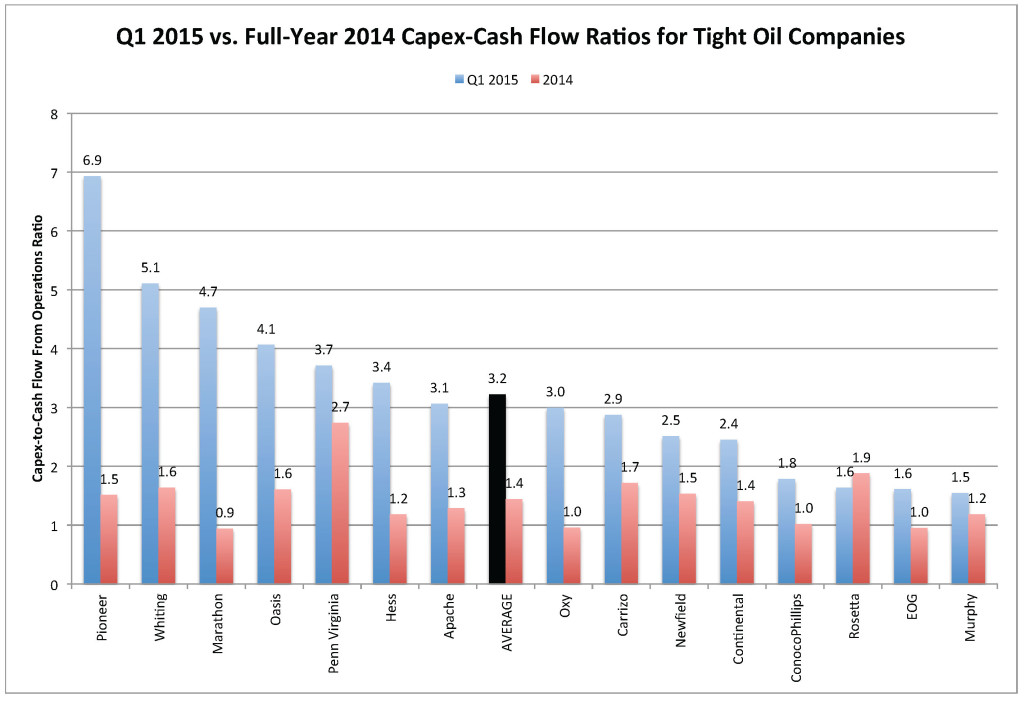

Tight oil companies have made the case that through increased efficiency and lower service costs that their economics are better at lower oil prices today than they were at $90 per barrel prices a few years ago. First quarter (Q1) financial results do not support this claim. In fact, tight oil companies are losing more than twice as much money in Q1 2015 as they were in 2014. On average, companies that were spending $1.40 for every dollar they earned from operations last year are now spending $3.20 for every dollar earned (Figure 12).

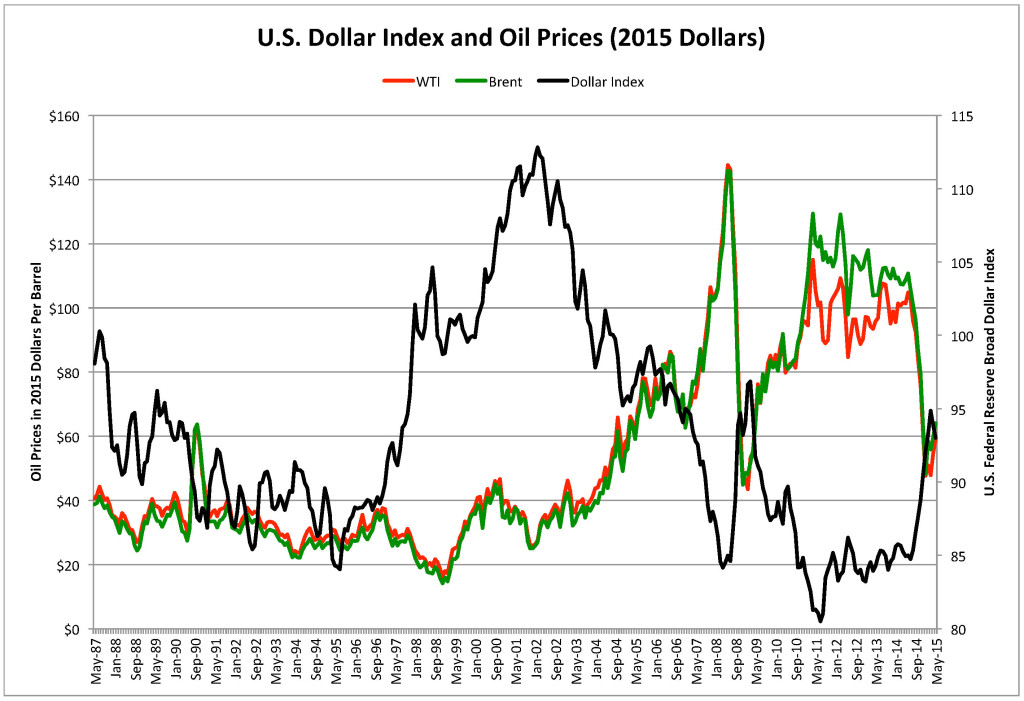

Follow The Money The strength of the U.S. dollar provides a simple and generally reliable way to cut through the complex factors that govern oil prices. A negative correlation exists between the strength of the U.S. dollar and the price of oil (Figure 13). This correlation is particularly strong beginning in about 1997.

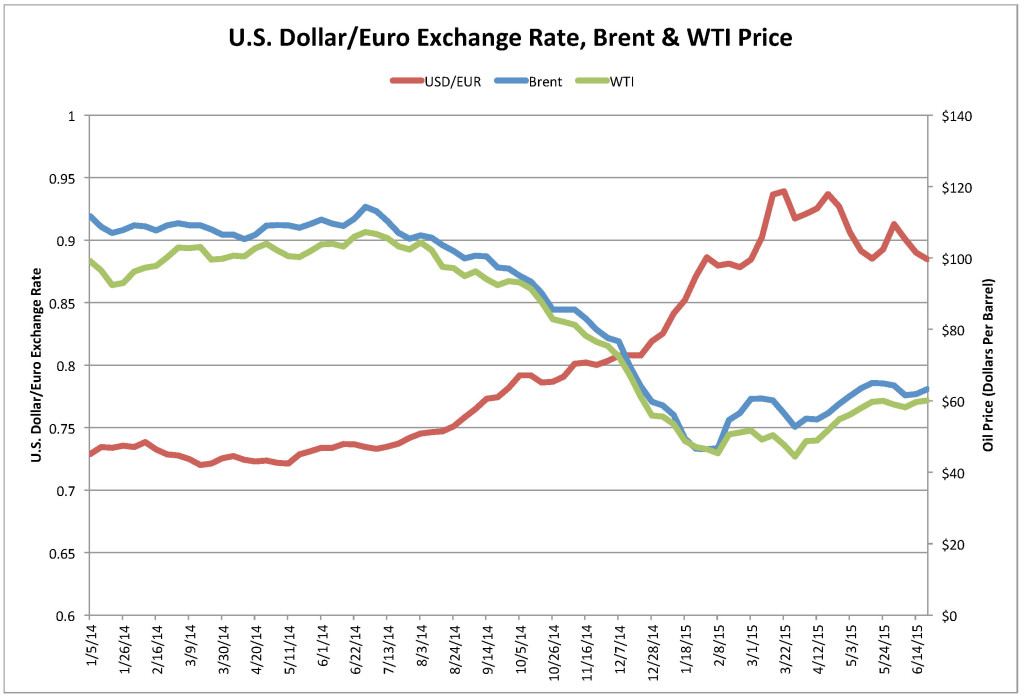

The relationship is key to understanding the current oil-price collapse. Figure 14 shows the daily exchange rate of the U.S. Dollar and the Euro in relation to Brent and WTI crude oil prices. The onset of price decline coincided with a stronger U.S. dollar beginning in June 2014 that may be related to the end of quantitative easing and to an improving U.S. economy. The recent increase in oil prices in 2015 corresponds to weakening of the dollar that may reflect disappointingly weak first quarter 2015 U.S. GDP growth.

The standard explanation for the relationship between the dollar and oil price is that global oil transactions are carried out in U.S. dollars. When the dollar is weak against other currencies, oil prices are higher and when the dollar is strong, oil prices are lower. In other words, a stronger U.S. economy and currency may reduce oil prices and vice versa. While the observation is accurate, the explanation is more complex. Oil and other commodities are hedges against economic risk and uncertainty. Oil prices increase and decrease as risk perception rises and falls. High oil-supply risk or “fear premiums” generally manifest as short-lived, upward price spikes that are quickly integrated into forward price expectations. Following the initial shock of oil-supply risk, U.S. Treasury bond and related “flight-to-safety” investments tend to lower oil price trends as the U.S. dollar appreciates. Supply and demand balance operates as a first-order cycle against which economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk fluctuate as second- and third-order cycles. When a first-order supply imbalance coincides with second- or third-order economic or geopolitical factors, an upward or downward price-cycle may develop. Higher energy costs are a weight on the economy that may lower currency values. Conversely, lower energy costs may lift the economy and currency values. The U.S. is the world’s largest economy and the U.S.dollar is the world reserve currency. This makes the U.S. dollar a fairly reliable reflection and measure of all of these factors. The 2014-2015 oil price collapse may be understood then as a supply surplus that occurred at a time of a strengthening U.S. economy (low economic uncertainty) and relatively low geopolitical risk (Figure 15). The additive effect of these three cycles was a sharp decline in oil prices.

Are Low Oil Prices Long or Short Term? Oil price collapses in 1981-1986 and 2008-2009 are the only analogues for the present price situation (Figure 16). So far, the current price collapse seems more similar to 1981-1986 than to 2008-2009.

1981-1986 was a long-term event. The price collapse itself lasted for 5 years but oil prices remained below $90 per barrel in real dollars until 2007, almost 27 years. 2008-2009 was a short-term event. Prices began falling in July 2008 and reached a low point in December 2008. Prices recovered and reached $90 per barrel in April 2010 and $100 per barrel in March 2011. Then entire cycle from $90 per barrel and back again lasted a little more than 2 years. The oil price collapse of the 1980s was similar to the present price collapse because the primary cause was a new source of supply. Non-OPEC production exceeded OPEC production in 1978 as new supply from the North Sea (U.K. and Norway), western Siberia (Russia), the Campeche Sound (Mexico) and China came on line. Unlike the present, the new supply was inexpensive conventional oil. Oil prices had increased in 1979-1981 to more than $90 per barrel in real dollars because of supply interruptions at the beginning of the Iran-Iraq war. This caused approximately 4.3 mmbpd of demand destruction. Lower demand and continued supply growth from non-OPEC countries caused a production surplus beginning in 1982. Oil prices fell from $106 per barrel in 1980 to $31 per barrel in 1986. OPEC cut 10 mmbpd of production between 1980 and 1985 with no effect on falling oil prices. In 1986, OPEC decided to increase production to protect market share, abandoning its role as “swing producer.” Although neither the volume of new supply or the amount of demand destruction during the current price collapse are as great as 1981-1986, they are more similar than to 2008-2009. The 2008-2009 oil price collapse was part of an overall crash of the entire global economy. High oil prices in 2007 and 2008 were due to a large and persistent production supply deficit because of high demand from China and the Far East, and dwindling supplies following the peak of conventional oil production in 2005 (Figures 15 and 17). The surplus had nothing to do with new supply but was completely due to decreased demand from a collapsing global economy. The surplus only lasted for 6 months and never approached the level seen in 2014-2015 (an OPEC production cut in early 2009 limited the length of the surplus and possibly its magnitude).

High oil prices preceding the 2014-2015 price collapse began because of supply interruptions resulting from the Arab Spring. Brent price reached a maximum of $129 per barrel in April 2011 at the height of the Libyan Civil War. These events corresponded with a period of U.S. currency devaluation following the 2008 Financial Collapse and an extraordinarily weak U.S. dollar (Figures 13 and 15). The additive effects of a supply deficit, economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk resulted in high oil prices. Case histories neither predict the present or the future but offer guidelines. These two case histories simply suggest is that the present period of low oil prices is more similar to that of the 1980s and 1990s than to that of the 2008-2009 period. That similarity means that the current phenomenon is likely to be a relatively long-term event. Conclusions The availability of capital to fund unconventional production is the key to how long low oil prices will last going forward. If the flow of capital continues, then the production surplus and lower oil prices will also continue, assuming that OPEC is able to maintain higher production levels and that demand growth remains relatively low. Eventually, price will win and unconventional production will fall. The market will rebalance and prices will rise. If oil prices stay low for long enough, demand will increase to support those higher prices. I doubt that prices will increase to levels before mid-2014 barring politically driven shock events. $90 per barrel appears to be the empirical threshold price above which demand destruction begins. It is more difficult to predict how the second- and third-order effects of economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk may affect supply and demand fundamentals and, therefore, price. These are the wild cards that could change the outcome that I describe. The most likely case is that oil prices will decrease in the second half of 2015 and that financial distress to all oil producers will increase. The hope and expectation that the worst is over will fade as the new reality of prolonged low oil prices is reluctantly accepted. We have had a year of lower oil prices. Based on available data, I see no end in sight yet. The market must balance before things get better and prices improve. That can only happen if production falls and demand increases. That will take time. We have crossed a boundary and things are different now. |

|||

"BEST OF THE WEEK " MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT & THEMES ARTICLES THIS WEEK June 28th, 2015 - July 4th, 2015 |

|||

| BOND BUBBLE | 1 | ||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 2 | ||

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | 3 | ||

GEO-POLITICAL EVENT RISK - Greece, Puerto Rico, China and France Greece Will Default To IMF Tomorrow, Government Official SaysTyler Durden on 06/29/2015Earlier today, as the exchange between Greece and its creditors got increasingly belligerent, Estonian Prime Minister Taavi said that "Greece’s debt would still remain outstanding and creditors would expect this money back." So did this latest antagonism change the Greek mind? According to a flash headline by the WSJ released moments ago, not all. In fact, Greece just made it official that it would default to the IMF in just over 24 hours: "Greece won't pay IMF tranche due Tuesday, government official says"

Puerto Rico Announces Bond Payment "Moratorium" Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015 Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015

Having concluded last night that Puerto Rico debt is "unpayable," and that his government could not continue to borrow money to address budget deficits while asking its residents, already struggling with high rates of poverty and crime, to shoulder most of the burden through tax increases and pension cuts, Padilla confirmed tonight that: PUERTO RICO TO SEEK "NEGOTIATED MORATORIUM", 'YEARS' OF POSTPONEMENT IN DEBT PAYMENTS. Likening his state's situation to that of Detroit and New York City (though not Greece), Padilla concluded, the economic situation is "extremely difficult," which is odd because just a few years ago when they issued that bond - everything was awesome? Strap In! China Is Crashing Again Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015 Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015

In the last 2 days, PBOC has thrown everything at the ponzi-fest they call a rational market. An RRR cut, a Benchmark rate cut, a rev repo rate cut, a CNY50 Bn rev repo injection, a stamp duty cut, IPO halts (cut supply), and last but not least permission to speculate with a reassurance that shares on a solid foundation. The outcome of all this policy-panic - CHINEXT (China's Nasdaq) is down another 6% today (down 25% in 3 days) and aside from CSI-300 futures, all other major Chinese indices are in free-fall. Add to that the fact that industrial metals are collapsing with steel rebar limit down and it appears Central Bank Omnipotence is under threat. French Economy In "Dire Straits", "Worse Than Anyone Can Imagine", Leaked NSA Cable Reveals Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015 Tyler Durden on 06/29/2015

Moscovici who served as French finance minister until 2014 and then became European commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs, used some very colorful language, i.e., the French economic situation was "worse than anyone [could] imagine and drastic measures [would] have to be taken in the next two years”. |

06-30-15 | GLOBAL RISK | 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 06-30-15 | GLOBAL RISK | 3 - Geo-Political Event | |

| Posted by Cliff Küle at 6/30/2015 04:53:00 PM | |||

16 Facts1. On Monday, the Dow fell by 350 points. That was the biggest one day decline that we have seen in two years.

|

|||

| 06-30-15 | GLOBAL RISK | 3 - Geo-Political Event | |

| Posted by Cliff Küle at 6/30/2015 05:58:00 AM | |||

The Euro CrisisAlasdair Macleod sees the criticality of the Greek crisis as being central to the solvency of the European Central Bank (ECB) itself & therefore confidence in the euro currency .. "The ECB's balance sheet, which is heavily dependent on Eurozone bond prices not collapsing, is itself extremely vulnerable to the knock-on effects from Greece. As the situation at the ECB becomes clear to financial markets, the euro's legitimacy as a currency may be questioned, given it is no more than an artificial construct in circulation for only thirteen years. In conclusion, the upsetting of the Greek applecart risks destabilizing the euro itself, and a sub-par rate to the U.S. dollar beckons."

|

|||

| 06-30-15 | GLOBAL RISK | 3 - Geo-Political Event | |

| Posted by Cliff Küle at 6/30/2015 05:56:00 AM | |||

Europeans Rush to Gold Coins as Bank of Greece Stops SalesBloomberg reports that European investors are increasing their purchases of gold as Greece's crisis intensifies .. "Investors are searching for a safe haven after Greece imposed capital controls, closed banks and stopped selling gold coins to the public until at least July 6."

|

|||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 4 | ||

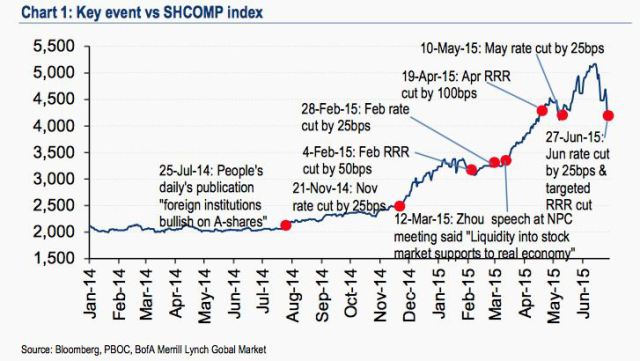

Early China Strength Fades Fast As Margin Debt Plunges Most In 3 YearsWed, 01 Jul 2015 05:16:47 GMTFollowing the much-celebrated (and massive 13% swing low-to-high) bounce yesterday at the hands of a desperate PBOC, the morning session ended with an early boost fading. Shanghai margin debt has now suffered the longest streak of declines in 3 years and as BofAML warned they "doubt that this marks the end of the de-leveraging process in the stock market given that much of the leveraged positions are yet to unwind." With both Manufacturing and Services PMIs printing above 50, stimulus is now clearly aimed at maintaining the bubble but as BofAML concludes, "after this adverse experience, we expect many investors will be much more cautious before investing into the stock market, we will be surprised to see a return of the unbridled enthusiasm of investors any time soon."

Not the follow through everyone was hoping and praying for after Greece defaulted... To summarize:

* * * Longer term, the psychological damage from the two-week long sharp market decline may linger for a while. This means that any market rebound will unlikely be strong in our view.

|

|||

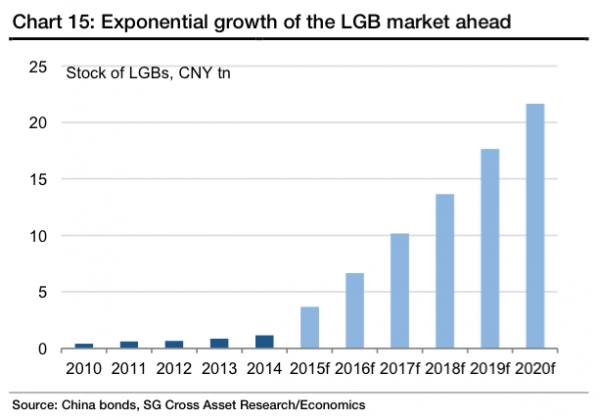

Chinese QE Calls Officially Begin: Bond Swap "Sucks Liquidity", "Contributes To Stock Slump", Broker ClaimsPosted:Wed, 01 Jul 2015 00:40:00 GMTOn Monday, we highlighted what we called an “insane” debt chart and explained what it means for the PBoC. Here’s a recap:

As a reminder, we've long said China's LGB refi initiative would eventually form the backbone of Chinese QE. Here is what we said in March when the program was in its infancy: "It seems as though one way to address the local government debt problem would be for the PBoC to simply purchase a portion of the local debt pile and we wonder if indeed this will ultimately be the form that QE will take in China." Similarly, UBS has suggested that when all is said and done, the PBoC will end up buying the new munis outright. From a March client note:

And so, here we are barely a month into the new LGB debt swap initiative (which, you're reminded, hasalready morphed into a Chinese LTRO program after the PBoC, recognizing that banks would be generally unwilling to take a 300bps hit in the swap, promised to allow participating banks to pledge the new munis for cash loans which can then be re-lent in the real economy at 6-7%) and the calls have begun for outright QE. Here's Bloomberg:

Note that this rather hyperbolic appeal for implementing full-on QE in China checks all the boxes: there's a reference to bond market illiquidy, an assertion about constraints on bank balance sheets (which, with credit creation stalling in China, is a big deal), and most importantly, a contention that somehow, the LGB debt swap program is contributing to the implosion of China's all-important equity bubble. A few more 'independent' assessments like these is likely all the PBoC will need to justify joining the global QE parade.

|

|||

How China Lost an Entire Spain in 17 DaysPosted:Tue, 30 Jun 2015 22:58:45 GMTBy EconMatters Concerned about a tumbling equity market, PBOC moved to cut both interest rates and the reserve requirement ratio for banks over the weekend. However, increasingly wary of a market bubble in China, investors still sent Shanghai Composite spiraling down another 3.3% on Monday after the dramatic 7.4% plunge last Friday despite the support from the central bank.

Investors are also unnerve by the latest development of Greece just days before a total default and Grexit out of EU, and the news that Puerto Rico could become another Greece of the U.S. facing a financial crisis and cannot pay back its $70 billion in municipal debt. Read: China's $370 Billion Margin Call VIX Spike MarketWatch reported that VIX spiked 33% to above 18, the highest since February, implying that investors are very nervous about the chaos going around. Beijing Targets Soft Landing? If you think U.S. stocks are lofty trading at an average of 16 times last year's earnings, the average Chinese stock is now trading at 30 times earnings. Analysts at HSBC think the China's central bank was trying to engineer a "soft landing" for stocks. But this could be a difficult balancing act trying to shore up investors' confidence while keeping a lid on the speculative fever among Chinese retailer investors (Remember those Chinese housewives who bought up 300 tons of gold and made Goldman Sachs swallow their gold selling recommendation?) Read: Is China Under The Skyscraper Curse? $1.3 trillion, an Entire Spain, in 17 Days

Size Does Matter Only time will tell if Beijing's able to turn the situation (i.e. slowing economy with a bubbling equity market) around. But if the world's biggest trading nation suddenly has a crisis of some sort, it would be a catastrophe of a different scale. Size does matter when it comes to financial collapse, and China could do far worse damage than any Grexit or PIIGS debt default. Chart Source: Quartz |

|||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 5 | ||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

6 |

||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market | |||

| TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

| STUDY - FUNDAMNENTALS | |||

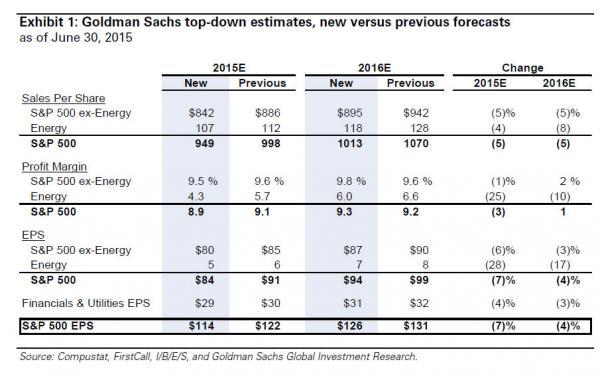

FUNDAMENTALS -The Truth "Slipped Out" Under Cover of Political Turmoil Goldman Just Crushed The "Strong Fundamentals" Lie; Cuts EPS, GDP, Revenue And Profit Forecasts Tyler Durden on 06/30/2015 Tyler Durden on 06/30/2015

To summarize: the first revenue drop for the S&P in 5 years, a major downward revision in EPS now expecting just 1% increase in 2015 EPS, a 25% cut to GDP forecasts, a machete taken to corporate profits and 10 Yields, and not to mention double digit sales declines for some of the most prominent tech companies in the world. And that, in a nutshell, is the "strong fundamentals" that everyone's been talking about. SEE BELOW FOR EXPANDED ARTICLE DETAIL

Gross Says Hold Cash, Prepare For "Nightmare Panic Selling" Submitted by Tyler Durden on 06/30/2015 - 15:21 Submitted by Tyler Durden on 06/30/2015 - 15:21

That an ETF can satisfy redemption with underlying bonds or shares, only raises the nightmare possibility of a disillusioned and uninformed public throwing in the towel once again after they receive thousands of individual odd lot pieces under such circumstances.

|

07-01-15 | STUDY | |

| 07-01-15 | STUDY | ||

Goldman Just Crushed The "Strong Fundamentals" Lie; Cuts EPS, GDP, Revenue And Profit ForecastsPosted:Wed, 01 Jul 2015 02:15:06 GMTIn the past week, the one recurring theme among the permabullish parade on financial propaganda TV has been to ignore the closed stock market and banks in suddenly imploding Greece, the situation in Puerto Rico, the recent plunge in US stocks which are now unchanged for the year, and what may be the beginning of the end of the Chinese bubble and instead focus on the "strong" US fundamentals, especially among tech stocks - the only shiny spot an an otherwise dreary landscape (and definitely ignore the energy companies; nobody wants to talk about those). So we decided to take a look at just what this "strength" looks like. Well, we already saw the collapse in hedge fund hotel Micron Technology, which plunged 30% after it slashed its guidance last week. Alas that may be just the beginning. Here are the year-over-year revenue "growth" estimates for some of the biggest tech companies in Q2:

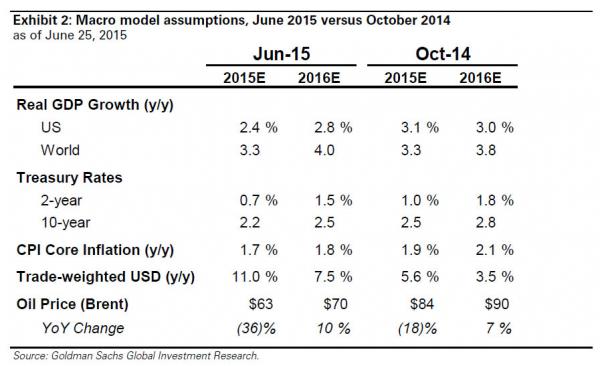

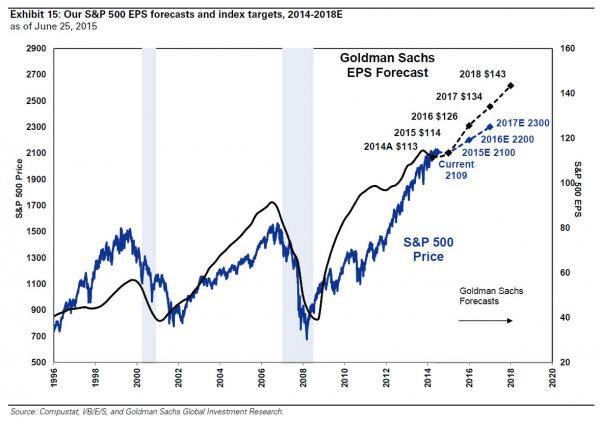

And that is the best sector among the "strong fundamentals" story. In fact, the only bright light in the entire tech space may well be AAPL whose sales are expected to grow 29%. We wish Tim Cook lot of strength if the recent Chinese market crash has dampened discretionary spending and demand for AAPL gizmoes in China. He will need it. But what's worse is that while reality will clearly be a disaster, there is always hype and always hope that the great rebound is just around the corner, if not in Q2 then Q3, or Q4, etc. This time even the hype is be over because none other than the most influential bank on Wall Street, the one all other sellside "strategists" religiously imitate, Goldman Sachs, just slashed its EPS and S&P500 year end price forecast for both 2015 and 2016. Here is Goldman with its explanation why it is lowering S&P 500 EPS:

However...

So earnings are bad and getting worse, but for Goldman that is not a reason to cut its S&P forecast simply because the economy is weaker than expected and also getting worse which means the rate hike originally forecast to take place in June is now set to take place in December, and thus boost P/E multiples (it won't of course but that will be Greece's fault).

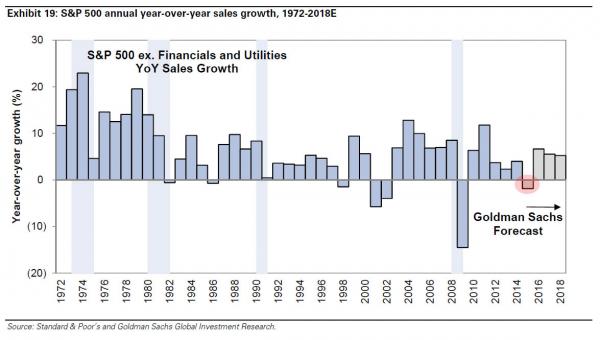

So... the combination of deteriorating earnings and an even bigger slowdown in the economy ends up being a wash and keeping the S&P year end price target at 2100. Ah, the magic of financial Goldman's financial gibberish. So aside from Goldman's 21x forward multiple (because 114 non-GAAP is about 100 GAAP which means Goldman is expecting a 21 Price to GAAP Earnings multiple) simply due to the Fed's hike delay from June to December, is there any good news? No. In fact, this is what Goldman's David Kostin has to say: "Macro headwinds diminish 2015 earnings growth prospects. S&P 500 sales will fall by 2% in 2015, the first annual decline in five years. Margins will slip to 8.9%. Energy is a drag on both sales and margins." Let's just focus on the "near-term" slip before we worry about the "long-term rebound." And before the intrepid questions of "this is only due to energy" arise, here is Goldman explaining that the weakness was broad, and impacted every single sector.

But wait, there's more: because in addition to its EPS forecast, Goldman also slashed its GDP and the 10Y yield forecast as well.

So ok, Goldman had a 25% error in its forecast in just under 9 months. Does that mean that the vampire squid is even remotely remorseful or concerned about the credibility of its 2017 and 2018 (yes, 2018) forecasts? Not at all: those are expected to remain completely unchanged on the back of some of the highest EPS gains in recent history. In fact, putting in context, Goldman now expects just 1% EPS growth in 2015 which will then magically soar to 11% in 2016 before "stabilizing" to a "modest" 7% annual EPS growth rate.

With just a little hyperbole, we can say that the only way S&P EPS will grow at that pace is if the S&P ends up buying back half its float. But while one can double seasonally adjust non-GAAP BS until a massive loss becomes a huge profit, one item can not be fabricated: sales. It is here that Goldman has far less to say for obvious reasons.

Yes you read that right "sales per share", because if buybacks can boost Non-GAAP earnings, why not revenues too. If there is a silver lining on the horizon it is one: "We forecast Health Care will grow sales faster than consensus expects." The corporations thank you Obamacare. * * * So to summarize: the first revenue drop for the S&P in 5 years, a major downward revision in EPS now expecting just 1% increase in 2015 EPS, a 25% cut to GDP forecasts, a machete taken to corporate profits and 10 Yields, and not to mention double digit sales declines for some of the most prominent tech companies in the world. And that, in a nutshell, is the "strong fundamentals" that everyone's been talking about.

|

|||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| SECURITY-SURVEILANCE COMPLEX | PORTFOLIO | ||

| THEMES | |||

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

FINANCIAL REPRESSION Is Financial Repression Here to Stay?

The First Chairman of the UK's Financial Services Authority Howard Davies writes an essay on financial repression .. "Maybe it is unreasonable for investors to expect positive rates on safe assets in the future. Perhaps we should expect to pay central banks and governments to keep our money safe, with positive returns offered only in return for some element of risk." .. Davies worries about the consequences of financial repression on the economy .. he sees distortions from the prudential regulation adopted in reaction to the financial crisis - "The question for regulators is whether, in responding to the financial crisis, they have created perverse incentives that are working against a recovery in long-term private-sector investment."

BCA Research Chief Economist Martin Barnes: "Financial Repression is Here to Stay" BCA Research's Chief Economist Martin Barnes sees financial repression as "here to stay" for the long-term, given the challenges of low economic growth & high debt globally .. Barnes has written a special report to explain why debt burdens are moe likely to rise than fall over the short & long run given demogaphic trends & the low odds of another economic boom .. BCA Research: "If governments cannot easily bring debt ratios down to more sustainable levels, then the obvious solution is to make high debt levels easier to live with. This can be done be keeping real borrowing costs down and by regulatory pressures that encourage financial institutions to hold more government securities. In other words, financial repression is the inevitable result of a world of low growth and stubbornly high debt. Martin argues that central banks are not overt supporters of financial repression, but they certainly are enablers because they have no other options other than to keep rates depressed if they cannot meet their growth and/or inflation targets. A world of financial repression is an uncomfortable world for investors as it implies continued distortions in asset prices, and it is bound to breed excesses that ultimately will threaten financial stability." LINK HERE to the Article & Link to Report

The Era of Financial Repression: Norway's Sovereign Wealth Fund says Monetary Policy is a Risk to Watch

“Monetary policy does affect pricing in today’s market to such an extent that monetary policy itself has been a risk you have to watch .. Investors are focused more on monetary policy changes than has been generally the case, than at any time, as far as I can remember .. As anything that moves prices is a risk that has to be monitored, here the effects of monetary policy affect prices dramatically .. It’s of course always been the case with long rates, and now more significantly with the currency. That’s just a fact of the current market." - Yngve Slyngstad, chief executive officer of Norway’s $890 billion sovereign-wealth fund "Financial repression is not a conspiracy theory, it is rather a collective set of macroprudential policies focused on controlling and reducing excessive government debt through 4 pillars - negative interest rates, inflation, ring-fencing regulations and obfuscation - to effectively transfer purchasing power from private savings." - The Financial Repression Authority

|

06-29-15 | ||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday Themes Post & a Friday Flows Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

|||

| CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM | THEME | ||

- - CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION, SHORTAGES. |

THEME |  |

|

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | M | THEME | |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | |

II-ECONOMIC |

|||

| GLOBAL RISK | |||

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | |

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | |||

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | THEME | MACRO w/ CHS |

|

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME |  |

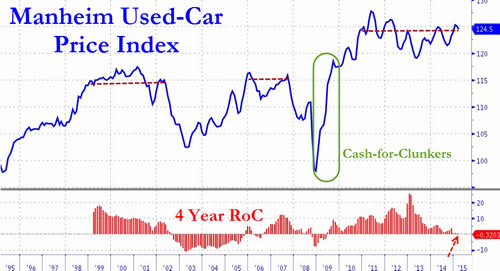

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY -Auto Loans Just as Used Car prices start to roll over again... (for the first time since the financial crisis, 4-year price changes - average term then - are now negative)

Worse yet, the most popular compact car prices are down 5.2% YoY and mid-size down 1.9% YoY. As Goldman notes,

|

07-02-15 |

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY |

|

| 07-02-15 |

SUB-PRIME ECONOMY |

|

|

Tyler Durden on 06/24/2015 20:30 -0400

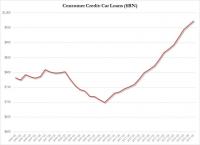

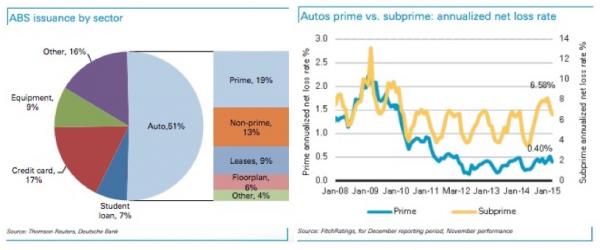

Auto Loans In "Untested" Territory Blackstone Warns As Subprime ABS Sales AccelerateEarlier this month, we gave readers a snapshot of the US auto market on the way to explaining why it was that car sales hit a 10-year high in May. To recap:

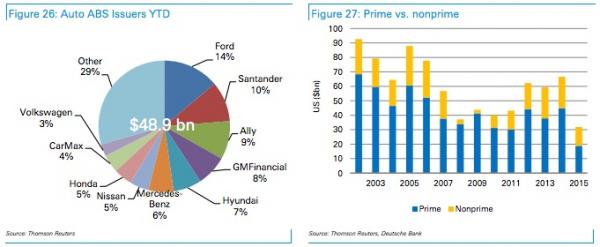

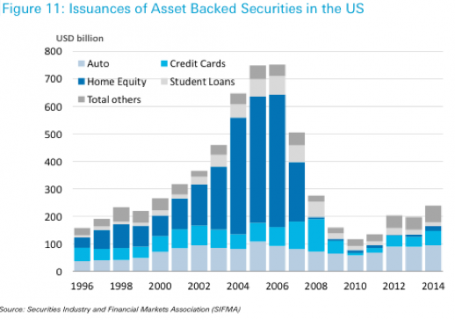

We went on to note that despite the worrying statistics shown above, optimists (like Experian) will likely point to the fact that the average FICO score for borrowers financing new cars fell only slighty from 714 to 713 Y/Y while the same Y/Y scores for those financing used vehicles actually rose from 641 in Q1 2014 to 643 in Q1 2015. While that's all well and good, there's every indication that those figures are likely to deteriorate significantly going forward. Why? Because Wall Street's securitization machine is involved. in the consumer ABS space (which encompasses paper backed by student loans, credit cards, equipment, auto loans, and other, more esoteric types of consumer credit), auto loan-backed issuance accounts for half of the market and a quarter of auto ABS is backed by loans to subprime borrowers. Put simply, those subprime borrowers are getting subprimey-er. In other words, the same dynamic that prevailed in the US housing market prior to the collapse is at play in the auto loan market. Lenders are competing for borrowers as lucrative securitization fees beckon, and this competition is directly responsible for loose underwriting standards. Bloomberg has more on the interplay between auto ABS issuance and “stretched” auto loan terms:

Here's a visual overview of the auto loan-backed ABS market (note the resurrgence of subprime as a percentage of total issuance post-2009 and the rising net loss rates):

* * * The takeaway here is simple: under pressure to keep the US auto sales miracle alive and feed Wall Street's securitization machine (which is itself driven by demand from yield-starved investors) along the way, lenders are lowering their underwriting standards and extending loans to underqualified borrowers. Particularly alarming is the fact that even as average loan terms hit record highs, average monthly payments are not only not falling, but are in fact also sitting at all-time highs. This cannot and will not end well. |

|||

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 02/21/2015 20:14 -0400 Subprime Car Loan Bubble 2.0 Full FrontalWith the total balance of auto loans for new and used vehicles approaching $1 trillion in the U.S., the folks at Experian want you to know that no matter what the numbers say, there’s no speculative bubble forming in the industry. Just ask Melinda Zabritski, the group’s director of automotive finance, who is quick to dismiss the growing chorus of Chicken Littles who are concerned about subprime auto lending:

That would be great if it were true. Of course the reality is that, according to the NY Times, early delinquencies (i.e. borrowers who have missed a payment within 8 months of origination) are at their highest level since 2008:

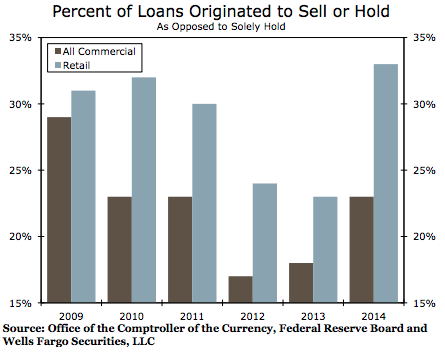

Combine that with the fact that the percentage of total auto loan originations made to subprime borrowers surged to 27% in 2013 (the highest level since 2006), the same year that 1.1 million U.S. households took out auto title loans (i.e. the new home equity loan), and you’ve got a rather strong argument for the contention that anything we learned in 2008 about the perils of loose lending standards has now been completely forgotten. Reinforcing this point is Wells Fargo, who notes that things are now officially back to “normal,” where “normal” is amusingly defined by the conditions that prevailed in 2006:

Of course the bad news is that Americans are again overextended at just the wrong time:

The prudent thing to do, from a lender’s perspective, is to tighten standards when it appears borrowers are exhibiting a propensity to take on an undue amount of risk. Instead, standards are actually falling as risk-taking increases:

And, not surprisingly, recklessness is most prevalent in the two categories that have combined to underpin consumer credit growth post-crisis:

Most disturbing of all, lenders seem to have reverted to their pre-crisis mindset: “If we can sell the loan, who cares about the creditworthiness of the borrower?” In 2014, a third of all firms originated retail loans with the intent to sell or hold the loan (as opposed to the sole intention to hold the loan). This trend indicates that some firms could be extending loans that they consider less creditworthy and could be eager to get these higher-risk loans off of their balance sheets. As a reminder, ABS issuance hit its highest level since the crisis last year with student and auto loans accounting for the lion’s share. That's no coincidence. |

|||

III-FINANCIAL |

|||

| FLOWS -FRIDAY FLOWS | MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt |

07-03-15 | THEMES | FLOWS |

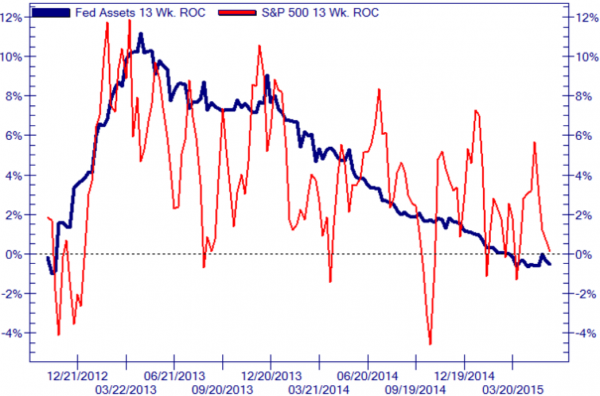

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 06/05/2015 13:35 -0400 It's Not The Economy, Stupid, It's The FlowBy now it should be clear, without the flow of Federal Reserve funny money, the wedge between the reality of collapsing macro- and micro-fundamentals and ever-expanding valuation hope-based stock prices is bound to close... and that is why the following 2 charts must be scary for Janet (and every asset-gathering commission-taking talking head out there). The Wedge: (the Fed-engineered gap between reality and unicorns) And the flow: (the rate of change of The Fed balance sheet - as opposed to the level or 'stock' of The Fed balance sheet - is what matters after all, via NJC)

So once again we'll ask, as we have ever since 2014: is the Fed simply rising rates just so it badly crashes the economy and has the cover to launch QE4, the same way Russian sanctions crippled Germany's economy and led to the ECB's very first episode of bond monetization? |

|||

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 06/21/2015 21:36 -0400

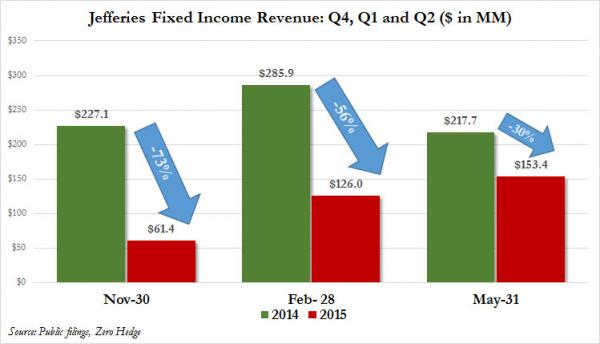

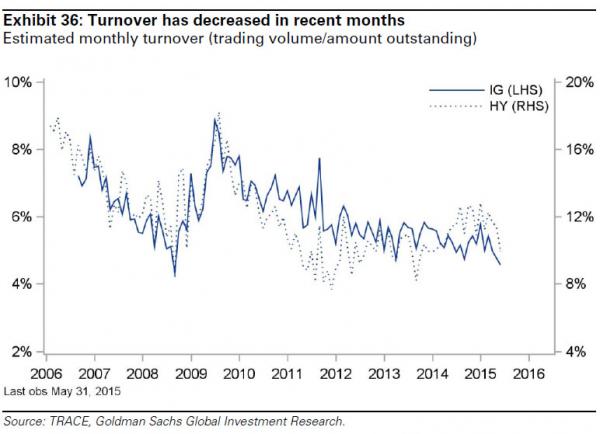

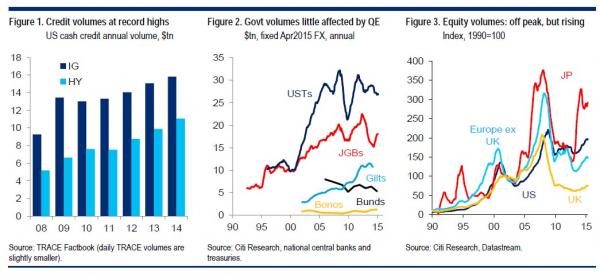

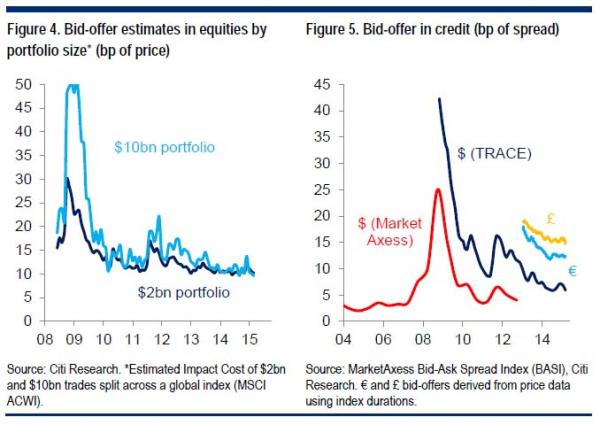

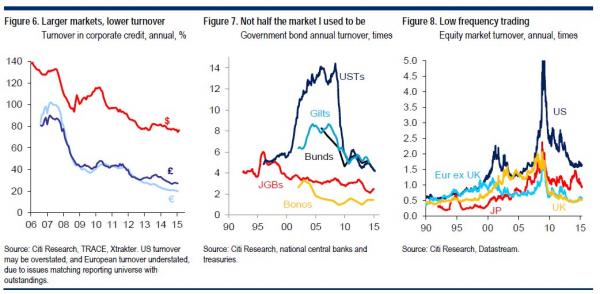

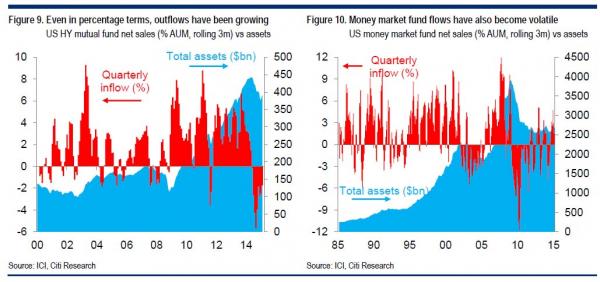

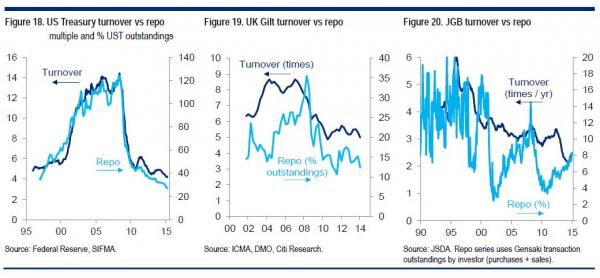

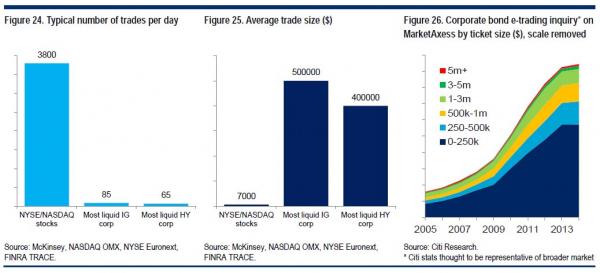

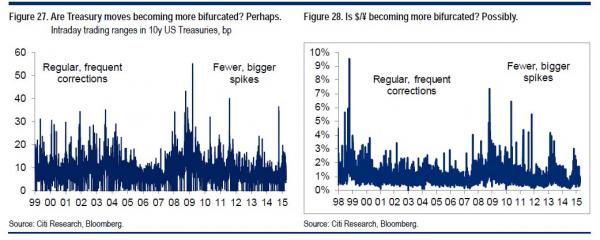

Bond Trading Revenues Are Plunging On Wall Street, And Why It Is Going To Get WorseAmong the renewed Greek drama, many missed a key development in the past week, namely Jefferies Q2 earnings, and particularly the company's fixed income revenue: traditionally a harbinger of profitability for Wall Street's biggest source of profit (or at least biggest source of profit in the Old Normal). And while not as abysmal as the 56% collapse in the first quarter, in the three months ended May 31 what has traditionally been the bread and butter of Dick Handler's operation generated just $153 million in revenue. CEO Handler blamed that decline on a lack of trading in the market and fewer companies selling junk bonds. To be sure, Q2 was better than the paltry $126 million in the previous quarter, however, the streak of year-over-year declines is now becoming very disturbing for a bank for which an ongoing collapse in fixed income trading will spell certain doom for any ambitious expanion plans, and most likely will result in dramatic headcount reductions to the point where not even fired UBS bankers will be able to find a job at what has long been known as Wall Street's "safety bank." Unfortunately for both Jefferies and all of its other FICC-reliant peers, we have bad news: the drought in fixed income profits is only going to get worse for two main reasons: turnover, as a function of collapsing liquidity in all markets not just debt, has plunged to match the lowest levels in history, and while junk bond turnover is not quite record low yet, it is rapidly approaching its lowest print as well.

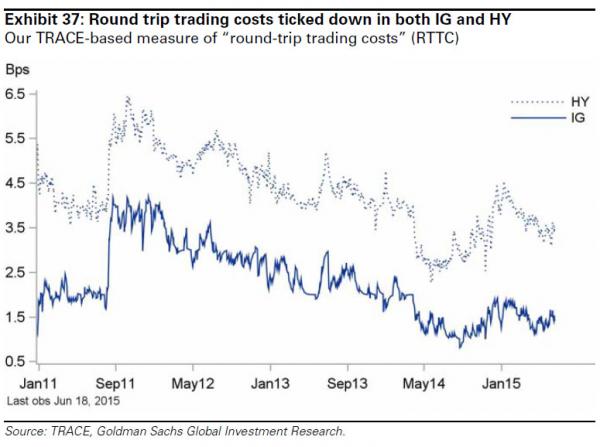

But it is not just turnover that is cratering. Even worse is that as electronic trading is increasingly penetrating this final frontier for Virtu (which recently fully took over FX trading leading to now weekly if not daily USD flash crashes following a headline overload), in addition to lack of trading interest (because in a centrally-planned market nobody sells until everybody sells... into a bidless market), the bid/ask spreads are collapsing as every broker fights tooth and nail for those last remaining pennies. In short: anyone hoping that the Goldmans of the world will fare any better than Jefferies (which unlike the aforementioned hedge fund has far less revenue diversification and is thus forced to extract every possible dollar from the product line) in the fixed income trading drought, will be disappointed, and as a result very soon even that business which until the mid-2000s was Wall Street's quiet goldmine will become commoditized to the point where Virtu algos make flash crashing junk debt a daily routine. Ironically, the only thing that can "save" this once-most profitable product line for Wall Street is the full-blown return of risk and volatility, resulting in a surge in trading i.e., selling. Just as ironic: the only thing which can save market cheerleading CNBC's sinking ratings is a market crash. Well, CNBC may be too late for saving, but if Wall Street one day realizes that it will be best suited should another crash take place, then one can be certain that that is precisely what will happen. The only question is who will be the sacrificial lamb that unleashes the next risk tsunami in the post-Lehman world.

|

|||

Submitted by Tyler Durden on 06/04/2015 21:58 -0400 The Real Reason Why There Is No Bond Market Liquidity LeftBack in the summer of 2013, we first commented on what we called "Phantom Markets" - displayed quotes and prices, in not only equities, FX and commodities but increasingly in government bonds, without any underlying liquidity. The problem, which we first addressed in 2012, had gotten so bad, even the all important Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee to the US Treasury had just sounded an alarm on the topic. Since then we have sat back and watched as our prediction was borne out, as bond market liquidity slowly devolved then sharply and dramatically collapsed recently to a level that is so unprecedented, not even we though possible, leading first to the October 15 bond flash crash and countless "VaR shock" events ever since. And while we urge those few carbon-based life forms who still trade for a living to catch up on our numerous posts on market "liquidity" and lack thereof, here is a quick and dirty primer on just why there is virtually no bond market left, courtesy of the man who, weeks ahead of the Lehman collapse when nobody had any idea what is going on, laid out precisely what happens in 2008 and onward in his seminal note "Are the Brokers Broken?", Citigroup's Matt King. Here is the gist of his recent note on the liquidity paradox which is a must read for everyone who trades anything and certainly bonds, while for the TL/DR crowd here is the 5 word summary: blame central bankers and HFTs. * * * The more liquidity central banks add, the less there is in markets