|

JOHN RUBINO'SLATEST BOOK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

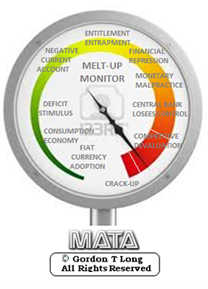

"MELT-UP MONITOR " Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - The Currency Cartel Carry Cycle - 09 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: FLOWS - Liquidity, Credit & Debt - 04 Dec 2013 Meltup Monitor: Euro Pressure Going Critical - 28- Nov 2013 Meltup Monitor: A Regression-to-the-Exponential Mean Required - 25 Nov 2013

|

"DOW 20,000 " Lance Roberts Charles Hugh Smith John Rubino Bert Dohman & Ty Andros

|

HELD OVER

Currency Wars

Euro Experiment

Sultans of Swap

Extend & Pretend

Preserve & Protect

Innovation

Showings Below

"Currency Wars "

|

"SULTANS OF SWAP" archives open ACT II ACT III ALSO Sultans of Swap: Fearing the Gearing! Sultans of Swap: BP Potentially More Devistating than Lehman! |

"EURO EXPERIMENT"

archives open EURO EXPERIMENT : ECB's LTRO Won't Stop Collateral Contagion!

EURO EXPERIMENT: |

"INNOVATION"

archives open |

"PRESERVE & PROTE CT"

archives open |

RECAP

Weekend Feb. 14th , 2016

Follow Our Updates

on TWITTER

https://twitter.com/GordonTLong

AND FOR EVEN MORE TWITTER COVERAGE

![]()

| FEBRUARY | ||||||

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | |||||

KEY TO TIPPING POINTS |

| 1- Bond Bubble |

| 2 - Risk Reversal |

| 3 - Geo-Political Event |

| 4 - China Hard Landing |

| 5 - Japan Debt Deflation Spiral |

| 6- EU Banking Crisis |

| 7- Sovereign Debt Crisis |

| 8 - Shrinking Revenue Growth Rate |

| 9 - Chronic Unemployment |

| 10 - US Stock Market Valuations |

| 11 - Global Governance Failure |

| 12 - Chronic Global Fiscal ImBalances |

| 13 - Growing Social Unrest |

| 14 - Residential Real Estate - Phase II |

| 15 - Commercial Real Estate |

| 16 - Credit Contraction II |

| 17- State & Local Government |

| 18 - Slowing Retail & Consumer Sales |

| 19 - US Reserve Currency |

| 20 - US Dollar |

| 21 - Financial Crisis Programs Expiration |

| 22 - US Banking Crisis II |

| 23 - China - Japan Regional Conflict |

| 24 - Corruption |

| 25 - Public Sentiment & Confidence |

| 26 - Food Price Pressures |

| 27 - Global Output Gap |

| 28 - Pension - Entitlement Crisis |

| 29 - Central & Eastern Europe |

| 30 - Terrorist Event |

| 31 - Pandemic / Epidemic |

| 32 - Rising Inflation Pressures & Interest Pressures |

| 33 - Resource Shortage |

| 34 - Cyber Attack or Complexity Failure |

| 35 - Corporate Bankruptcies |

| 36 - Iran Nuclear Threat |

| 37- Finance & Insurance Balance Sheet Write-Offs |

| 38- Government Backstop Insurance |

| 39 - Oil Price Pressures |

| 40 - Natural Physical Disaster |

Reading the right books?

No Time?

We have analyzed & included

these in our latest research papers Macro videos!

![]()

OUR MACRO ANALYTIC

CO-HOSTS

John Rubino's Just Released Book

Charles Hugh Smith's Latest Books

Our Macro Watch Partner

Richard Duncan Latest Books

MACRO ANALYTIC

GUESTS

F William Engdahl

OTHERS OF NOTE

Book Review- Five Thumbs Up

for Steve Greenhut's

Plunder!

|

Have your own site? Offer free content to your visitors with TRIGGER$ Public Edition!

Sell TRIGGER$ from your site and grow a monthly recurring income!

Contact [email protected] for more information - (free ad space for participating affiliates).

HOTTEST TIPPING POINTS |

Theme Groupings |

||

We post throughout the day as we do our Investment Research for: LONGWave - UnderTheLens - Macro

|

|||

|

MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES TODAY

|

|

||

TIPPING POINTS, STUDIES, THESIS, THEMES & SII COVERAGE THIS WEEK PREVIOUSLY POSTED - (BELOW)

|

|||

| MOST CRITICAL TIPPING POINT ARTICLES THIS WEEK - Feb 7th, 2016 to Feb 13th, 2016 | |||

| TIPPING POINTS - This Week - Normally a Tuesday Focus | |||

| BOND BUBBLE | 1 | ||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 2 | ||

| RISK REVERSAL - WOULD BE MARKED BY: Slowing Momentum, Weakening Earnings, Falling Estimates | 02-09-6 | 2 | |

22 Signs That The Global Economic Turmoil We Have Seen So Far In 2016Is Just The BeginningSubmitted by Michael Snyder via The Economic Collapse blog, As bad as the month of January was for the global economy, the truth is that the rest of 2016 promises to be much worse. Layoffs are increasing at a pace that we haven’t seen since the last recession, major retailers are shutting down hundreds of locations, corporate profit margins are plunging, global trade is slowing down dramatically, and several major European banks are in the process of completely imploding. I am about to share some numbers with you that are truly eye-popping. Each one by itself would be reason for concern, but when you put all of the pieces together it creates a picture that is hard to deny. The global economy is in crisis, and this is going to have very serious implications for the financial markets moving forward. U.S. stocks just had their worst January in seven years, and if I am right much worse is still yet to come this year. The following are 22 signs that the global economic turmoil that we have seen so far in 2016 is just the beginning… 1. The number of job cuts in the United States skyrocketed 218 percent during the month of January according to Challenger, Gray & Christmas. 2. The Baltic Dry Index just hit yet another brand new all-time record low. As I write this article, it is sitting at 303. 3. U.S. factory orders have now dropped for 14 months in a row. 4. In the U.S., the Restaurant Performance Index just fell to the lowest level that we have seen since 2008. 5. In January, orders for class 8 trucks (the big trucks that you see shipping stuff around the country on our highways) declined a whopping 48 percent from a year ago. 6. Rail traffic is also slowing down substantially. In Colorado, there are hundreds of train engines that are just sitting on the tracks with nothing to do. 7. Corporate profit margins peaked during the third quarter of 2014 and have been declining steadily since then. This usually happens when we are heading into a recession. 8. A series of extremely disappointing corporate quarterly reports is sending stock after stock plummeting. Here is a summary from Zero Hedge of a few examples that we have just witnessed…

9. Junk bonds continue to crash on Wall Street. On Monday, JNK was down to 32.60 and HYG was down to 77.99. 10. On Thursday, a major British news source publicly named five large European banks that are considered to be in very serious danger…

11. Deutsche Bank is the biggest bank in Germany and it has more exposure to derivatives than any other bank in the world. Unfortunately, Deutsche Bank credit default swaps are now telling us that there is deep turmoil at the bank and that a complete implosion may be imminent. 12. Last week, we learned that Deutsche Bank had lost a staggering 6.8 billion euros in 2015. If you will recall, I warned about massive problems at Deutsche Bank all the way back in September. The most important bank in Germany is exceedingly troubled, and it could end up being for the EU what Lehman Brothers was for the United States. 13. Credit Suisse just announced that it will be eliminating 4,000 jobs. 14. Royal Dutch Shell has announced that it is going to be eliminating 10,000 jobs. 15. Caterpillar has announced that it will be closing 5 plants and getting rid of 670 workers. 16. Yahoo has announced that it is going to be getting rid of 15 percent of its total workforce. 17. Johnson & Johnson has announced that it is slashing its workforce by 3,000 jobs. 18. Sprint just laid off 8 percent of its workforce and GoPro is letting go 7 percent of its workers. 19. All over America, retail stores are shutting down at a staggering pace. The following list comes from one of myprevious articles… -Wal-Mart is closing 269 stores, including 154 inside the United States. -K-Mart is closing down more than two dozen stores over the next several months. -J.C. Penney will be permanently shutting down 47 more stores after closing a total of 40 stores in 2015. -Macy’s has decided that it needs to shutter 36 stores and lay off approximately 2,500 employees. -The Gap is in the process of closing 175 stores in North America. -Aeropostale is in the process of closing 84 stores all across America. -Finish Line has announced that 150 stores will be shutting down over the next few years. -Sears has shut down about 600 stores over the past year or so, but sales at the stores that remain open continue to fall precipitously. 20. According to the New York Times, the Chinese economy is facing a mountain of bad loans that “could exceed $5 trillion“. 21. Japan has implemented a negative interest rate program in a desperate attempt to try to get banks to make more loans. 22. The global economy desperately needs the price of oil to go back up, but Morgan Stanley says that we will not see $80 oil again until 2018. It is not difficult to see where the numbers are trending. Last week, I told my wife that I thought that Marco Rubio was going to do better than expected in Iowa. How did I come to that conclusion? It was simply based on how his poll numbers were trending. And when you look at where global economic numbers are trending, they tell us that 2016 is going to be a year that is going to get progressively worse as it goes along. So many of the exact same things that we saw happen in 2008 are happening again right now, and you would have to be blind not to see it. Hopefully I am wrong about what is coming in our immediate future, because millions upon millions of Americans are not prepared for what is ahead, and most of them are going to get absolutely blindsided by the coming crisis. |

|||

| GEO-POLITICAL EVENT | 3 | ||

| CHINA BUBBLE | 4 | ||

| JAPAN - DEBT DEFLATION | 5 | ||

EU BANKING CRISIS |

6 |

||

| TO TOP | |||

| MACRO News Items of Importance - This Week | |||

GLOBAL MACRO REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

US ECONOMIC REPORTS & ANALYSIS |

|||

| CENTRAL BANKING MONETARY POLICIES, ACTIONS & ACTIVITIES | |||

| Market - WEDNESDAY STUDIES | |||

| STUDIES - MACRO pdf | |||

TECHNICALS & MARKET |

|

||

TECHNICALS & MARKET |

02-10-16 |

||

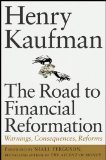

Two New Concerns Weighing On Risk

The biggest worries challenging that bull case in January were twofold: China and commodities, mostly oil. However, over the past week, two new big concerns appear to have emerged. Here, ironically, is Deutsche Bank explaining what these are (for those confused, "tightening in financial conditions in European financial credit" is a euphemism for plunging DB stock among others):

And here is the matrix breaking down all the recent conditions weighing on risk. We wish we could be as optimistic as DB that monetary support from central banks which are now running on fumes in terms of credibility, and that oil, which continues to gyrate with grotesque daily volatility, are "supportive. In fact, we are confused that DB is optimistic on central bank support: after all it was, drumroll, Deutsche Bank, which over the weekend warned against any more "easing" from central banks whose NIRP is now weighing on the German bank's profitability, something the market has clearly realized judging by the price of its public securities. |

|||

| COMMODITY CORNER - AGRI-COMPLEX | |||

| THESIS - Mondays Posts on Financial Repression & Posts on Thursday as Key Updates Occur | |||

|

2016 | THESIS 2016 |  |

| 2015 - FIDUCIARY FAILURE | 2015 | THESIS 2015 |  |

| 2014 - GLOBALIZATION TRAP | 2014 |  |

|

|

2013 2014 |

|||

| 02-08-16 | |||

John Charalambakis:IT’S ABOUT RISK MITIGATION & CAPITAL PRESERVATION!

John Charalambakis is the Managing Director of Group, a boutique style asset and wealth management firm, which focuses on risk mitigation, capital preservation and growth through strategies that are rule based. Dr. Charalambakis has been teaching economics and finance in the US for the last twenty years. Currently he teaches economics at the Patterson School of Diplomacy & International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. FINANCIAL REPRESSION“The outcome of financial repression is when the role of the markets is diminished because of the actions of central authorities, such as central banks.” Fed: Central banks of the United States, ECB: European central bank, and BoJ Bank of Japan Assets under management have skyrocketed from about 7% in 2007 for the U.S Fed, to over 20% as of the end of 2015, increasing 3 times. Over this time, the GDP did not equally increase 3 times. This increase eventually leads to a greater role of central authorities. Looking at Japan in 2007, they had about 20% of their GDP in their balance sheet, currently they have over 90%, meaning the role of the markets is diminishing and the role of central authorities is increasing, creating financial repression. Gord asks John what assets people should invest in, in this era of financial repression that would create a store of value, which may not bring in a yield, but would preserve their money. GOLD – INTRINSIC VALUE ASSETS “I think the goal of any pension fund, institutional or private investor should be capital preservation. Assets should have intrinsic value.” “Assets that have intrinsic value such as gold or silver, historically have retained their value especially in times of crisis.” John mentions how the price of gold in 2009 rose from about $500-$500 to $1900 because investors were seeking a safe haven of intrinsic value assets. “There is not enough gold for everyone. Only 1/3 of 1%, a miniscule number, is invested in precious metals.” Hypothetically if every manager by the end 2016 would invest just 3% of their wealth into precious metals, the price of gold would rise to an estimated $2700. Growing demand and financial stress can, and likely eventually will, create a financial crisis. KEY PRINCIPLES OF THE AUSTRIAN SCHOOL OF THOUGHT

“Unfortunately risks and stresses are being built up and portfolios are suffering the consequences. People think because they have wealth on a financial statement, that wealth can be preserve. When the markets collide, that wealth is destroyed because it is paper wealth, not real wealth.” INFASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT “Infrastructure investment needs to be financed, usually countries finance infrastructure through deficit spending, and that cannot happen due to big holes in their budgets.” John questions whether or not the internal rate of return justifies infrastructure. He doesn’t believe the environment is mature enough currently, due to the possibility of a looming crisis in the next couple years. This would push back infrastructure spending. PREPARING FOR A POSSIBLE CRISIS

“Since we are in an era of financial repression you cannot expect the income from treasuries or CDs, explore all sources of income”

Kamilla Guliveva

|

|||

2011 2012 2013 2014 |

|||

| THEMES - Normally a Thursday "Themes" Post & a Friday "Flows" Post | |||

I - POLITICAL |

|||

CENTRAL PLANNING - SHIFTING ECONOMIC POWER - STATISM

MACRO MAP - EVOLVING ERA OF CENTRAL PLANNING

|

G | THEME | |

| - - CRISIS OF TRUST - Era of Uncertainty | G | THEME | |

CORRUPTION & MALFEASANCE - MORAL DECAY - DESPERATION - RESENTMENT. |

US | THEME PAGE |  |

| - - SECURITY-SURVEILLANCE COMPLEX - STATISM | G | THEME | |

| - - CATALYSTS - FEAR (POLITICALLY) & GREED (FINANCIALLY) | G | THEME | |

II-ECONOMIC |

|||

| GLOBAL RISK | |||

| - GLOBAL FINANCIAL IMBALANCE - FRAGILITY, COMPLEXITY & INSTABILITY | G | THEME | |

"Negative Rates Are Dangerous"OECD Chair Warns"Our Entire System Is Unstable"Posted:Thu, 11 Feb 2016 01:00:00 GMTSubmitted by Erico Matias Tavares via Sinclair & Co., William R. White is the chairman of the Economic and Development Review Committee at the OECD in Paris. Prior to that, Dr. White held a number of senior positions with the Bank for International Settlements (“BIS”), including Head of the Monetary and Economic Department, where he had overall responsibility for the department's output of research, data and information services, and was a member of the Executive Committee which manages the BIS. He retired from the BIS on 30 June 2008. Dr. White began his professional career at the Bank of England, where he was an economist from 1969 to 1972. Subsequently he spent 22 years with the Bank of Canada. In addition to his many publications, he speaks regularly to a wide range of audiences on topics related to monetary and financial stability. In the following interview he shares his views in a totally personal capacity on the current state of the global economy and related monetary and fiscal policies. E. Tavares: Dr. White, we are delighted to be speaking with you today. You are recognized as one of the leading central bank economists in the world, and so your perspective is highly valued and appreciated. Absent the robust central bank intervention in 2008 the world’s financial system would have likely collapsed. However, in a sense the economy looks riskier now: government debt levels as a function of GDP are at record highs; big financial institutions have gotten even bigger; and while we may not have a housing credit crisis brewing in the US, we are seeing stress in many areas, from student loans to energy bank loans to emerging market convulsions. At the same time, income inequality has blown out of proportion as booming asset prices hardly benefited the less privileged in society. With the benefit of hindsight, can we say that the very loose monetary policy of central banks around the world lulled politicians and investors into a false sense of security and that those unresolved issues from the recent past could still come back to haunt them? Or can they keep things under control with these newly found monetary “bazookas”? W. White: I think your assessment of where we are at is spot on. What the central banks did in 2008 was totally appropriate. The markets were basically collapsing. We had a kind of a “Minsky moment” problem with market illiquidity and the central banks did what they had to do. Since then the focus has changed. I believe that it was in 2010 when Ben Bernanke, then Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, made clear in a speech that the objective of monetary policy – and specifically quantitative easing – was basically to stimulate aggregate demand. And since then we have had all the central banks around the world pursuing that objective through increasingly unconventional measures. However, there is a fundamental shortcoming in using monetary policy in this way. Just as you described it, the fundamental problem we all face is a problem of too much debt, you know, the headwinds of debt. In a sense it is a problem of insolvency. And relying on central banks to correct this is totally inappropriate, because they can handle problems of illiquidity but they can’t handle problems of insolvency. So I think that the fundamental orientation here is wrong. Now, why is this happening? In part, I think, it’s because dealing with problems of insolvency, debt reduction, making debt service more bearable and so forth, demands policies that only governments can implement. Moreover, these policies are likely to be technically hard to implement and will also meet stiff political resistance. You know there’s this old line from Daniel Kahneman: we have to believe – we are hardwired to believe – and so since we must believe then it’s just as well to believe in something convenient. And I think the politicians find it convenient to believe that the central banks have it all under control. But it’s not true, because what we have been doing is both losing efficacy over time, that is to say that the efficiency of the transmission mechanism seems to me to be getting less and less, while the impact of the associated unintended consequences, the side effects of monetary policy, are becoming more and more evident. In the end this is really going to cause us problems. And of all the unintended consequences I could list, lulling the governments into a false sense of security is probably the most important. ET: In a modern financial economy, liquidity is created primarily by the banks through credit creation. When that liquidity creation slows down typically the economy falters. So as the banks were forced to deal with credit and balance sheet issues from 2008 onwards, the central banks stepped into that role by cheapening the cost of credit and conducting large scale asset purchases to make sure that liquidity continued to flow throughout the economy. However, even that seems insufficient to rekindle economic growth, prompting some central banks to go a step further and adopt negative interest rates (“NIRP”). Japan is the latest convert. Is that the likely next step for other central banks, including the Fed? WW: I think it is entirely possible. But before I get into that I would like to comment first on the efficacy of monetary policy as you briefly outlined. The whole thing is premised firstly on the idea that easy money will stimulate demand, and secondly that the unintended consequences are nothing to worry about. On that first issue, I have very serious doubts whether the very easy money policies will have the impact that central bankers believe it should have. And after seven years of the slowest recovery ever, it seems to me that there is empirical support for that proposition. Now why do I think it won’t work? I think what they’ve done, particularly the unconventional stuff – and there has been so much of it, including forward guidance, quantitative easing, qualitative easing and now NIRP – has led many people into looking upon all of this as experimental policies smacking of panic. And, as a result of the associated uncertainty, they may have hunkered down instead of going out and spending the money. There’s another point which is closely related. Think about interest rates being brought down to very low levels. The whole point is trying to attract spending from the future into today, what is known as intertemporal reallocation. That is just fine. But if you’re bringing that spending forward, at a certain point when tomorrow becomes today – as indeed it must inevitably do – then that future spending that you might otherwise have done is constrained by the spending that you have already done. And that manifests itself in increasing debt levels, which indeed we have already seen. So, almost by definition, monetary policy only works for a relatively short period of time. We have had six or seven years of it at this point and I think that’s hardly a short period. There are all sorts of other issues that I won’t go into now, but that’s where we are. ET: If we have reached that exhaustion level, then the next step is NIRP right? Is that the natural progression given the “panic mindset” that you alluded to? WW: You used exactly the right word, it is a mindset. They believe that they understand how the economy works and they are going to do more of what they consider to be a good thing. And we’ve seen this process at work over the course of the years. I remind you that, when the Fed started this ultra-easy stuff, the Europeans were very hesitant to go into it. But, in the end, Mario Draghi and the ECB have gone into it with both feet and are proceeding along the broad lines of what the Americans initiated. The thing that strikes me about NIRP is the possible analogy between the zero lower bound and quantum mechanics. The Newtonian laws of motion apply as long as the body in motion is not too small and is not going too fast, otherwise you need to make use of quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity. And maybe with monetary policy there is a similar kind of a phase change that occurs at the zero lower bound. The Europeans were concerned about this, based on earlier Danish experience when the central bank started charging negative rates on excess reserves held by the banks at the central bank. The expectation is that this will lead to lower lending rates. But you can easily think of a story where this is not the outcome because those negative interest rates cut the banks’ profit margins. And then the question is what will the banks do to restore them? Well, one thing they could do is lower the deposit rate. I read in the Financial Times a few days ago that Julius Baer in Switzerland is thinking about doing just that. But then the worry is that people will take their money elsewhere, take it out in cash or whatever. If this is not possible, then what is possible is increasing the lending rate. What you end up with is a counterintuitive but highly plausible alternative description of what these policies are going to give you. So in the end they may end up being contractionary and not expansionary. So totally experimental in any event. ET: Actually we do have some empirical evidence after some central banks adopted NIRP, such as Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark. As interest rates fell, people saved more, which is the opposite of the policy objective. It seems that because people, particularly the older folks, earn less interest they have to save more to meet their needs. WW: Absolutely. But I would associate that argument more with the general question of whether additional quantitative easing will produce the desired increase in aggregate demand. The NIRP is sort of an extension of that kind of argument. There are lots of reasons why lower interest rates might produce lower consumption. For example, think about the people who are saving for an annuity or a pension for when they retire. If the roll-up rate is going down, aside from working longer, the only solution is to save more. You need a higher base, given that lower roll-up rate, to achieve a particular target level of wealth to buy an annuity of the desired size at the point in time when you want to retire. There are all these distributional issues to consider too. You know, all these policies have buoyed asset prices a lot and richer people – the ones who have the financial assets and the big houses whose values have increased the most – have gained the most. Conversely, middle class people whose financial assets are largely in the banks, have lost out. Since richer people tend to have a lower marginal propensity to consume out of both income and wealth, then these redistribution effects could cause the economy to grow more slowly, not more rapidly. Andrew Smithers of the Financial Times has offered a compelling explanation as to why business investment has also been so weak in spite of monetary conditions being so easy. It relates to the unexpected interaction between lower interest rates and corporate compensation schemes. When interest rates go down it becomes cheaper to borrow money, which can then be used to buy shares thus pushing up equity prices and the value of the associated option compensation schemes. So from the perspective of the senior management – and for that matter, the “sharp” holders of equities who know that the shares are overvalued – it makes a lot of sense to buy back shares because they are personally making a lot of money out of it. But in the process they are also hollowing out the corporation because they are cutting investment to hoard cash for the same reason. And the “dumb” holders who did not sell the shares in the buyback are left holding the bag. That shell of a corporation is not going to be able to produce the returns in the future the way it did in the past. And this is an unexpected consequence of the interaction between easy money and corporate compensation schemes. As you can see there are many reasons why lowering interest rates – and in the limit NIRP – could lead to less spending and not more. Having said that, I did notice from reading the newspapers how this thing is spreading out. Haruhiko Kuroda, the Governor of the Bank of Japan, until recently maintained that there was absolutely no way he would ever do NIRP, not even thinking about it. Then he went to Davos a couple of weeks ago, came back and did it. Insofar as the Americans are concerned, who are now outliers for not having negative rates, we had Ben Bernanke just two weeks ago saying the Fed should think about it. Alan Blinder apparently said it’s a good idea, and Janet Yellen, who previously said it is too dangerous, now says that the Fed should consider it. So here we have that mindset again. ET: It’s creeping in. You bring up a number of important counter-arguments that should be considered in policy making, which gives us some hope in our economics profession. And yet it seems the default is always more of the same, with the consequences we have been discussing. Let’s pick up on the issue of solvency you brought up earlier, which could also be frustrating the outcomes of central bank policies. We can use Portugal as a case study in this regard. Until recently it was under the direct economic supervision of major international financial institutions and all the brainpower that comes with it. The previous government, replaced only a few months ago, had been praised for implementing a very strict austerity program. And yet, the economy pretty much stagnated, unemployment remained high and government debt levels as a function of GDP exploded – to the point where nominal growth for the most part does not cover government interest payments. The banking sector in turn remains in a dicey situation, with several high profile bankruptcies just in the past months. While central banks are critical in providing liquidity, how can a country like Portugal become solvent again? WW: Here you have one of those unintended consequences I alluded to before. It turns out that these ultra-easy monetary policies induce people to take on more debt. In the longer run it’s those debt problems that become a headwind, and if that headwind is of such a magnitude that it affects the solvency of the banking system as well, then we have a real problem. There is now a huge literature on this. You are familiar with Ken Rogoff’s and Carmen Reinhardt’s book on financial follies over the ages which, along with pieces by Jorda, Taylor and Schularick and others, describe the dynamics at work here. When you get a combination of an economy which is hurting because of debt problems, where the corporate and/or the household sectors are facing these big headwinds of debt, and in addition the banking system becomes challenged, with non-performing loans and the like, the resulting periods of unusually low growth can go on for a decade or more. Carmen and Vincent Reinhardt also did a big paper at Jackson Hole on this in 2010 where I was the commentator. If you get a joint problem of this nature associated with too much debt both in and out of the financial system you have a tiger by the tail. Now specifically on Portugal, the McKinsey Global Institute recently published a paper on debt and deleveraging all over the world. Out of the six countries which had the biggest increase in sovereign debt to GDP ratios since 2007, four of them were in peripheral Europe, including Portugal. I have followed the Greek situation a little more closely and I know for a fact that in their case they have implemented actual fiscal measures that took out 18% of GDP out of the economy. In spite of this, and the fact that the private sector took a big haircut, the overall debt to GDP has risen to above 200% of GDP as GDP has sunk like a stone. ET: So, clearly, some of what has been done has made things worse, not better. The question is what are the alternative policies when you are dealing with a solvency problem of this nature? And related to that, how to make debt service more manageable? WW: The first thing I would say is to have less austerity and more pro-growth spending. Now I qualify each of these things with the recognition that sometimes and in some countries this will not be possible because of confidence effects in market. Nevertheless, European experience does point to the merits of less austerity as opposed to more. I particularly think that there are many countries, maybe Portugal is part of this, where there should be a lot more government money spent on infrastructure: the US, Germany, Canada, and the UK would certainly be included. There are needs for more infrastructure in many countries, and with the interest rates being so low, I really don’t understand what the hang up is. I also think that there are a number of countries following essentially mercantilist policies and it would be much better if they re-orientated themselves domestically so that wages could get a larger share of incomes. In countries like Germany, China, Japan, South Korea, for a long period of time and still continuing, that sort of mercantilist approach basically said that you have to keep wages down. I think that has not been helpful, and that we could do more to encourage wage income and spending in many countries. We also need many more write-offs – not just debt restructuring but actual reduction of the principal. Willem Buiter has written a lot on this, in terms of replacing debt with equity, so that the risks are more evenly shared. And lastly, we need more structural reforms. At the OECD, they believe that there’s still a lot of low hanging fruit out there, in terms of freeing up labor markets, product markets and so forth. The answer to insolvency is not simply to print more money – it may get you out of the problem in the short-run but it simply makes it worse and worse over time. At some point, maybe where we are now, you truly get to the end of a line. You see that what you have been doing is just a short term palliative that is actually making the disease worse. ET: We wrote about Greece a year ago and pointed out that the economic transformation being asked in connection with the new bailout was akin to converting a proverbial “couch potato” into an Olympic athlete almost overnight. Given how poorly they rank across a number of competitiveness statistics after being in the European Union for decades now, at best this is something that will take many more decades to turn around. It really makes you wonder what kind of shock therapy is needed to rehabilitate that economy. There’s one other policy that while a political taboo might also be considered: leaving the Euro. Greece has tried the alternative, which is austerity – internal devaluation by another name – with very poor results. So why not give this one a go? WW: This raises an important question. Suppose Greece exits and depreciates its new currency to stimulate exports and economic growth. Will depreciation prove successful? In addressing this question, we get back to some fundamental structural issues. There is in fact a developing literature on this topic at the moment. In part, this literature is a response to the puzzle that both the Japanese Yen and Sterling depreciated a lot recently yet nothing seemed to have happened in terms of the external side. I think there are a lot of grounds to believe that depreciation works less well than it used to. First, in Greece we know that wages have come down a lot. But the country is characterized by such a degree of oligopoly and rent-seeking that all that’s happened is that profit margins have gone up. As a result, there’s no signal coming through prices to get a change in resource allocation from non-tradables to tradables. Second, you have all sorts of institutional barriers to entry and to exit of old unproductive firms – in Greece it takes almost four years for your average bankruptcy proceeding. If you have all these institutional impediments to the resources actually moving from the non-tradables to the tradables this is an excellent reason why depreciation might not produce the results intended. Thirdly, it might not work because, in the end, all that will happen is that inflation will go up and any real benefits you may have gotten in the first instance just get eaten away. Now, we should be thinking about all these alternatives in a serious way. They are very important issues. But you should not just immediately assume that a depreciation is going to be output expanding, particularly via an improvement in the current account. Another thing that concerns me a great deal, and we can see this in spades inside the Eurozone, is that the portfolio elements and revaluations associated with depreciation are potentially much more important than trade effects. How are these people going to pay all these external debts which are denominated in Euros when they are earning revenues in a new but depreciated currency? To say nothing about the legal problems, there would be lawsuits left and right. George Soros made the point, in the Financial Times a while back, with an article titled “Germany Should Lead or Leave”. His view is that you could avoid a lot of problems if the Germans left, not the Greeks. When currency unions split up in the past, normally it was the creditors who left. They see the writing on the wall and they are out of it. If anyone leaves it should be the Germans, the Dutch or whoever wants to go along with them. The debtors would keep the euro, minimizing legal battles, and the creditors would have to be cooperative to minimize their losses. That’s what Soros thinks. The problems associated with leaving would be very great, so you would want to think very carefully about it. What are the benefits and what are the costs? Barry Eichengreen talked about this a few years ago in an article for Project Syndicate. He felt that an exit would precipitate the “mother” of all crises. And the other problem is you would have to do all your thinking in secret because the minute the people get a whiff of what was going on you would see the “mother” of all capital outflows. ET: What is your view on using actual cash – notes and bills – as a monetary tool to stimulate the economy? It seems to us that having a stimulus instrument that does not add to the debt burdens of countries has some appeal. And it goes straight to the real economy, bypassing bank managers who may be reluctant to lend that money out. Aren’t the Swiss voting on a similar scheme in fact? WW: I had an exchange of views in Project Syndicate with Adair Turner on this. Essentially what it comes down to is the question of helicopter money: the government spends the money and the central bank prints it. The particular variation here is you’re saying the government doesn’t actually spend the money; they just print the notes and give them to the ordinary citizens who will spend the notes. Well, a number of points can be made about this. If you give people notes, and you’re putting more notes into the economy than they want to hold, the first thing they’ll do is take the notes and deposit them in the banks again. So it really doesn’t make any difference whether a central bank pays for a deficit with notes or through a cheque that is deposited and shows up as increased reserves held by banks at the central bank. ET: True. They could also use them to reduce their debt loads… WW: Right, I was coming on to that. My first point is that there’s nothing magical about notes. People hold as many of them as they want and the rest they put in the bank. Now, I will contradict myself by saying that if the actual printing of notes was taken as a sign of the extraordinary problems being faced by the government, you could end up in a Zimbabwe-type scenario. And that could lead to hyperinflation almost immediately. OK, having said that, if you give people notes or a government cheque, what will they do with the money? They might spend it or, as you have just said, they might actually save it. The latter is more likely in a high debt environment. Whether it’s high existing levels of household sector debt, or whether it’s a Ricardian equivalence where they see-through the government and realize that government debt is really their debt and higher taxes down the line. So they might just sit on it and not spend it. In fact when you think about it, remember the old multiplier debate? Tax cut multiplier versus expenditure increase multiplier, which is greater? It was commonly said that the expenditure multiplier was larger because, when the government spent the money, it was buying goods and services with money that ended up in people’s pockets, which they could then spend again. But the problem with the tax cuts is that we’re back to what we just described. Getting a bank note or a check from the government is almost identical to a tax cut, the benefits of which you may or may not spend. The question is always what will the people do with the money? And I think the answer could be nothing. So this is a less useful way to approach the problem. If there is something to be said about government expansion – I stress the word “if” – there is less to be said about doing it through notes. Another thing worth mentioning is the suggestion that that the reserves held in the central bank are not debt. They are not liabilities of government. I think that’s just totally wrong. The central bank is 100% a creature of the government. So if you put the two balance sheets together and net them all out, whether it’s cash issued by the central banks, or whether it’s bank reserves on the liability side of the governments accounts, it’s all government debt. Well, then you might then say that there is no problem with this kind of debt because it is debt that doesn’t pay any interest. But what if there are so many reserves in the system that the central bank has to take them out at some point? And here the government really only has two choices: either the central bank sells assets, which are then interest bearing assets held by the private sector, or it pays interest rates on the reserves, in order to increase the demand for reserves commensurate with increased supply. So you end up in a world where you are paying interest on that debt. I think back to that article written by Sargent and Wallace in 1981 titled “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”. There’s also a book written by Peter Bernholz about monetary and political regimes and inflation. Both of those pieces, the first the theory and the second the historical facts, suggest that if a government is running a big deficit and it’s already got a big debt, it has a big problem. And the problem is that the government has to borrow because the deficit is so great and the employees need to get paid. However, nobody will lend them the money because the stock of debt outstanding is too high. And the only answer is to go back to the central bank. Peter has a magic number. If 40% of all of the expenditures of the government are being financed by the central bank, the historical record indicates that hyperinflation is significantly more likely. And what is really interesting at the moment in terms of magic numbers, for what all magic numbers are worth, is that the asset buying program at the Bank of Japan is now equivalent to financing 40% of government expenditures. We’re talking big numbers here. I don’t think you need rational expectations, just people seeing the writing on the wall. Everything is fine until inflationary pressures or something else shocks up the interest rates. And the minute they go up, it becomes obvious that government debt service has gone high enough so they will have no recourse but to have the central bank finance still more. And when that happens the writing is on the wall, the currency collapses and the inflation becomes essentially uncontrollable. This is a highly non-linear process that cannot be captured by the econometric models that are in widespread use. They are essentially linear. People say that all this stuff is innocuous, that “helicopter money” is a magic bullet to get us out of a debt problem. My own personal view – and I have to say that I hope I’m wrong – is that it is a highly risky and perhaps even terminally risky policy for countries that already have bad fiscal conditions. We should be thinking about the downsides. ET: If high inflation rears its ugly head again, do you think central banks won’t be able to fight it? For instance, given the high debt load the US government has taken in recent years massively raising interest rates to curb inflation could create some serious fiscal problems going forward. WW: I think it’s exactly so and it goes back to what we were just talking about. Suppose a country has a big debt, a big deficit, and a short maturity of debt and they raise interest rates. It’s entirely possible that this process of fiscal dominance not only begins but could be perceived to be beginning on the part of thoughtful investors. Then it turns into a flight to get out, and the flight then generates a dynamic which is self-fulfilling. If you ask me who I am worried about today, I guess Venezuela is on top of the list, albeit a bit of an outlier. Brazil is a country that I think is very worrisome, with high interest rates, a bad fiscal position and short maturities. The OECD over the course of the years has pointed out that Japan, the US and the UK are the countries that could have the most serious problems in this regard. However, the odd thing is that the OECD has been saying this for ages and yet everything in those three countries now has continued to be just fine. Conversely, you look at other countries like Ireland and Spain before the Eurozone crisis, which seemed to be perfectly fine, and yet the markets attacked them anyway. I suppose the bottom line is that, while we can see the potential dangers building up here, as to when they will materialize we have no real idea. ET: That’s the $57 trillion question as per the figure in that McKinsey report. It does seem that savers are surely facing some tough times ahead, with real and even nominal negative interest rates. WW: Absolutely. As soon as you get into these kinds of scenarios where further damage is being caused to the health of the middle class that is already under severe pressure – you mentioned income distribution earlier – then you do have to think in a very serious way about what the social and political ramifications might be. I mentioned before this group of researchers that included Martin Schularick. He began with a database documenting economic crises in a large number of countries over the last 100 years or so – a huge effort to pull this data together – and then expanded it to cover the political realm as well. He contends that after serious economic and financial crises it is very common to see a shift away from the political center, either to the left or the right. The left of course means more socialism and the right means more nationalism. The problem is that it’s all a big circle and you could end up with national socialism. So we definitely shouldn’t understate the social and political ramifications from all of this. ET: We’re seeing that in Europe and in the US, with candidates like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders. Switching gears to the current macro picture, what is your assessment of the global economy? Are we going into a generalized recession or is the slowdown confined to some geographical areas and sectors? What is your number one worry in that context right now? WW: As the whole tone of our conversation has indicated I’m fearful of a few things.

Any one of these things could be a trigger for broader global problems. My number one fear? That’s the same as asking me where it will start. When you view the economy as a complex, adaptive system, like many other systems, one of the clear findings from the literature is that the trigger doesn’t matter; it’s the system that’s unstable. And I think our system is unstable. Where could it start? Who knows, I’d probably say China but I have no idea and nobody has any idea. ET: Dr. White, thank you very much for sharing your thoughts. All the best to you. WW: Thank you.

|

|||

| - - SOCIAL UNREST - INEQUALITY & A BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACT | US | THEME | |

| - - ECHO BOOM - PERIPHERAL PROBLEM | M | THEME | |

| - -GLOBAL GROWTH & JOBS CRISIS | |||

| - - - PRODUCTIVITY PARADOX - NATURE OF WORK | THEME | MA w/ CHS |

|

| 01-08-16 | THEME | MA w/ CHS |

|

| - - - STANDARD OF LIVING - EMPLOYMENT CRISIS, SUB-PRIME ECONOMY | US | THEME | MA w/ CHS |

III-FINANCIAL |

|||

|

FLOWS - Liqudity, Credit & Debt

|

MATA RISK ON-OFF |

THEME | |

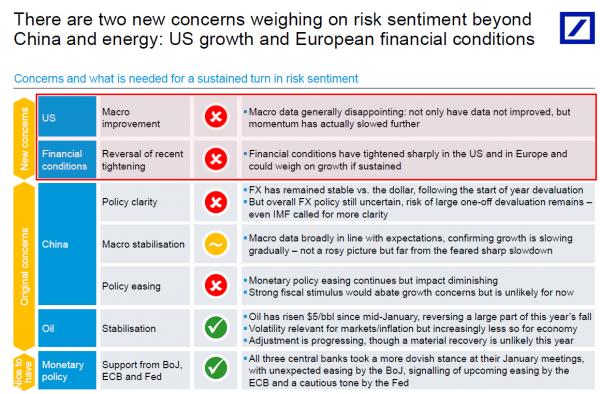

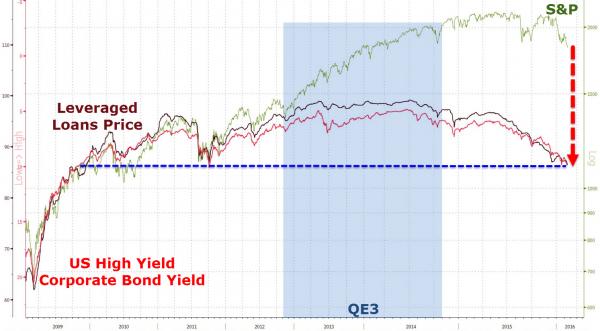

1,100 is the target... ...and credit is always right in the end! High Yield bond yields and Leveraged Loan prices are at their worst since 2009 as it seems the hosepipe of QE3 liquidity (its the flow not the stock, stupid) is slowly unwound from a buybacks-are-over equity market. |

|||

| CRACKUP BOOM - ASSET BUBBLE | 12-31-15 | THEME | |

| SHADOW BANKING - LIQUIDITY / CREDIT ENGINE | M | THEME | |

| GENERAL INTEREST |

|

||

| STRATEGIC INVESTMENT INSIGHTS - Weekend Coverage | |||

|

|||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

SII | ||

|

02-13-16 | SII | |

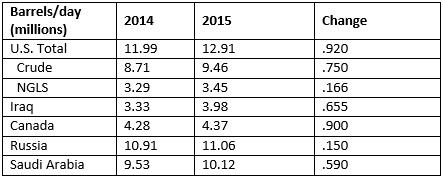

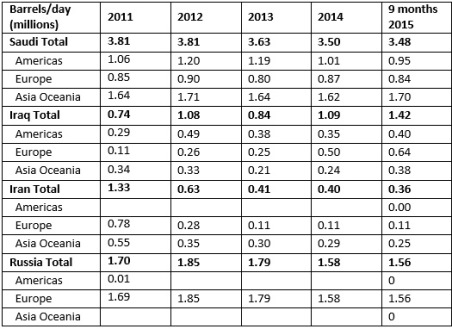

The Hidden Agenda Behind Saudi Arabia’s Market Share StrategySubmitted by Dalan McEndree via OilPrice.com, Do the Saudis have an oil market strategy beyond pumping crude to defend their market share? Are they indifferent to which countries’ oil industries survive? Or, alternatively, are they targeting specific global competitors and specific national markets? Did they start with a particular strategy in November 2014 when Saudi Petroleum and Mineral Resources Minister Ali al-Naimi announced the new market share policy at the OPEC meeting in Vienna and are they sticking with it, or has their strategy evolved with the evolution of the global markets since? And, of course, what does the Saudi strategy beyond pumping crude portend for the Saudi approach to some OPEC members’ calls for coordinated production cuts within OPEC and with Russia? Conventional Wisdom Conventional wisdom has it that the Saudis are focused primarily on crushing the U.S. shale industry.In this view, the Saudis blame the U.S. for the supply-demand imbalance that began to make itself felt in 2014. U.S. production data seems to support this. Between 2009 and 2014, U.S. crude and NGLs output increased nearly 4 million barrels per day, while Saudi Arabia’s increased only 1.64 million barrels per day, Canada’s 1.06 million, Iraq’s 0.9 million, and Russia’s 0.7 million (Saudi data doesn’t include NGLs).

In addition, the Saudis, among many others, believed that U.S. shale would be the most vulnerable to Saudi strategy, given relatively high production costs compared to Saudi production costs and shale’s rapid decline rates and the need therefore repeatedly to reinvest in new wells to maintain output. Yet, if the Saudis were focused on the U.S., their efforts have been unsuccessful, at least in 2015. As the table below shows, U.S. output growth in 2015 outstripped Saudi output growth and the growth of output from other major producers in absolute terms. In addition, many observers also came to believe that U.S. shale production will recover more quickly than production in traditional plays once markets balance due to its unique accelerated production cycle and that this quick recovery will limit price increases when markets balance.

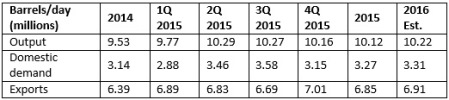

Is the U.S. Really the Primary Target? The above considerations imply the Saudis—if indeed they primarily were targeting U.S. shale—embarked on a self-defeating campaign in November 2014 that could at best deliver a Pyrrhic victory and permanent revenues losses in the US$ hundred billions. Is the U.S. the primary target? U.S. import data (from the EIA) suggests the U.S. is not now the Saudis’ primary target, if it ever was. Like other producers, the Saudis operate within a set of constraints. Domestic capacity is one. In its 2015 Medium Term Market Report (Oil), the IEA put Saudi Arabia’s sustainable crude output capacity at 12.34 million barrels per day in 2015 and at 12.42 million in 2016. Export capacity—output minus domestic demand—is another. Rather than maintaining crude output at 2014’s level in 2015, the Saudis steadily increased it after al-Naimi’s announcement in Vienna as they brought idle capacity on line (data from the IEA monthly Oil Market Report):

This allowed them to increase average daily crude exports by 460,000 barrels in 2015 over 2014 average export levels—even as Saudi domestic demand increased—and exports peaked in 4Q 2015 at 7.01 million barrels per day (assuming the Saudis keep output at average 2H 2015 levels in 2016, and domestic demand increased 400,000 barrels per day, as the IEA forecasts, the Saudis could export nearly 7 million barrels per day on average in 2016):

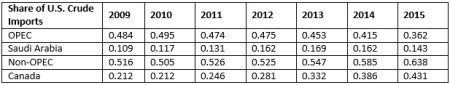

The Saudis did not ship any of their incremental crude exports to the U.S.—in other words, they did not increase volumes exported to the U.S., did not directly seek to constrain U.S. output, and did not seek to increase U.S. market share. Based on EIA data, Saudi imports into the U.S. declined from 1.191 million barrels per day in 2014 to 1.045 million in 2015—and have steadily declined since peaking in 2012 at 1,396 million barrels per day. (OPEC’s shipments also declined from 2014 to 2015, from 3.05 million barrels per day to 2.64 million, continuing the downward trend that started in 2010). Canada, however, which has sent increasing volumes to the U.S. since 2009, increased exports to the U.S. 306,000 barrels per day in 2015:

Also, the Saudi share of U.S. crude imports declined 1.9 percentage points in 2015 from 2014, and has declined 2.6 percentage points since peaking at 16.9 percent in 2013; during the same two periods, Canada’s share increased 4.5 and 9.9 percentage points respectively (and has more than doubled since 2009):

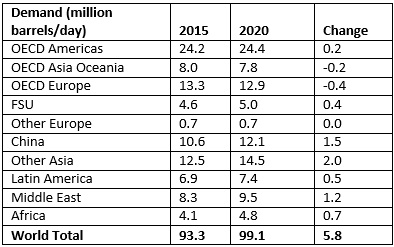

Other Markets The Saudis presumably exported the incremental 606,000 barrels per day (460,000 from net increased export capacity plus 146,000 diverted from the U.S.) to their focus markets. Since other countries’ import data generally is less current, complete, and available than U.S. data, where these barrels ended up must be found indirectly, at least partially. In its 2015 Medium Term Market Report (Oil), the IEA projected that the bulk of growth from 2015 to 2020 will come in China, Other Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, while demand will remain more or less stagnant in OECD U.S. and OECD Europe:

The Saudis find themselves in a difficult battle for market share in China, the world’s second largest import market and the country in which the IEA expects absolute import volume will increase the most through 2020—1.5 million barrels per day (it projects Other Asia demand to increase 2.0 million). The Saudis are China’s leading crude supplier. However, their position is under sustained attack from their major—and minor—global export competitors. For example, through the first eleven months of 2015, imports from Saudi Arabia increased only 2.1 percent to 46.08 million metric tons, while imports from Russia increased 28 percent to 37.62 million, Oman 9.1 percent to 28.94 million, Iraq 10.3 percent to 28.82 million, Venezuela 20.7 percent to 14.77 million, Kuwait 42.6 percent to 12.68 million, and Brazil 102.1 percent to 12.07 million. As a result of the competition, the Saudi share of China’s imports has dropped from ~20 percent since 2012 to ~15 percent in 2015, even as Chinese demand increased 16.7 percent, or 1.6 million barrels per day, from 9.6 million in 2012 to 11.2 million in 2015. Moreover, the competition for Chinese market share promises to intensify with the lifting of UN sanctions on Iran, which occupied second place in Chinese imports pre-UN sanctions and has expressed determination to regain its prior position (Iran’s exports to China fell 2.1 percent to 24.36 million tons in the first eleven months of 2015). Moreover, several Saudi competitors enjoy substantial competitive advantages. Russia has two. One is the East Siberia Pacific Ocean pipeline (ESPO) which directly connects Russia to China—important because the Chinese are said to fear the U.S. Navy’s ability to interdict ocean supplies routes. Its capacity currently is 15 million metric tons per year (~300,000 barrels per day) and capacity is expected to double by 2017, when a twin comes on stream. The second is the agreement Rosneft, Russia’s dominant producer, has with China National Petroleum Corporation to ship ~400 million metric tons of crude over twenty-five years, and for which China has already made prepayments. Russia shares a third with other suppliers. Saudis contracts contain destination restrictions and other provisions that constrain their customers’ ability to market the crude, whereas those of some other suppliers do not. Marketing flexibility will be particularly attractive to the smaller Chinese refineries, which Chinese government has authorized to import 1 million-plus barrels per day.

It is therefore not surprising that the Saudis moved aggressively in Europe in 4Q 2015—successfully courting traditional Russian customers in Northern Europe and Eastern Europe and drawing complaints from Rosneft. As with China, the competition will intensify with Iran’s liberation from UN sanctions. For example, Iran has promised to regain its pre-UN sanctions European market share—which implies an increase in exports into the stagnant European market of 970,000 barrels per day (2011’s 1.33 million barrels per day minus 2015’s 360,000 barrels per day). Might the U.S. be an Ally? Without unlimited crude export resources, the Saudis have had to choose in which global markets to conduct their market share war, and therefore, implicitly, against which competitors to direct their crude exports. Why did the Saudis ignore the U.S. market?

In this Saudi effort, the U.S. could be an ally. The U.S. became a net petroleum product exporter in 2012 (minus numbers in the table below indicate net exports), and net exports grew steadily through 2015. Growth continued in January, with net product exports averaging 1.802 million barrels per day, and, in the week ending February 5, 2.046 million. U.S. exports will lessen the financial attractiveness of investment in domestic refining capacity, both for governments and for foreign investors in their countries’ oil industries (data from EIA).

Saudi Intentions The view that the Saudi market share strategy is focused on crushing the U.S. shale industry has led market observers obsessively to await the EIA’s weekly Wednesday petroleum status report and Baker-Hughes weekly Friday U.S. rig count—and to react with dismay as U.S. rig count has dropped, but production remained resilient. In fact, they might be better served welcoming resilient U.S. production. It may be that the Saudis will not change course until Russian output declines, Iraq’s stagnates, Iran’s output growth is stunted—and that receding output from weaker countries within and outside OPEC would not be enough. If this is case, the Saudis will see resilient U.S. production as increasing pressure on their competitors and bringing forward the day when they can contemplate moderating their output. NOTE: Nothing in the foregoing analysis should be understood as denying that the U.S. oil industry has suffered intensely or asserting that this strategy, if it is Saudi strategy, will succeed. |

|||

| TO TOP | |||

Read More - OUR RESEARCH - Articles Below

Tipping Points Life Cycle - Explained

Click on image to enlarge

TO TOP

�

TO TOP